The Frank Stella You Thought You Knew

You may know Frank Stella from the brightly colored, shaped canvas paintings in his Protractor series from the late 1960s to early 1970s. However,...

Marva Becker 11 July 2024

Chinese art is booming. The country has been experiencing a major economic uplift for more than a decade and you can feel that in the art world too. China has more artists than ever, and they claim that a new museum opens every week. These are artistic heydays for the eastern country. Here is the contemporary art made in China.

Collectors of contemporary Chinese art, such as the Dutch couple Henk and Victoria de Heus-Zomer, claim that art flows with money. The wealthy Chinese are expanding their art collection. Interestingly, they not only collect established Western artists but also show a great deal of interest in Chinese artists. Why this upswing? A word of explanation.

The strength of these artists is their combination of the present and the past. China is changing fast and that is why many artists go back to the past. They know the most modern techniques and are aware of what is going on in the world, but at the same time, they can look back on a very rich cultural past and utilize all their traditional techniques, such as calligraphy. These two things seem to have a major influence on contemporary Chinese artists: in the interviews, I have read a kind of nostalgia emerges, a flight from the hectic world, but also a lot of criticism of past government politics. Because criticism is a delicate issue in Chinese society, most artists present it in a suggestive form. In other words, you will often have to learn more about a work in order to fully understand it. They treat their subjects with refined techniques and use calligraphy, the art of writing, as a basis; the slow brush strokes are ideal for unwinding and self-reflection.

The paintings and etchings of the versatile artist Shao Fan start from calligraphy. He starts with one smooth line and repeats it up to 1000 times. After a while, he gets a picture with meaning on the canvas. He also uses washed ink (a traditional Chinese painting technique) on rice paper. By applying the brush strokes, the paper deforms and starts showing relief, and the image on the paper, a rabbit in this case, consequently forms the structure of the animal’s fur.

Rabbits are one of his favorite animals. He keeps them in his house in an inner garden and has painted them numerous times. He enlarges the image of the vulnerable rabbits so that they appear rather dominant. Shao Fan said in an interview: “When you look down at them, they look like cute creatures, but I wanted to bring them on an equal footing with humans so that a dialogue can arise between the work and the viewer.” That says a lot about his love for animals.

Shao Fan not only expresses calligraphy in his art via paintings, but he also designs furniture inspired by Chinese characters. Combined with clean geometric lines, he gives Ming Dynasty furniture pieces a modern look. In this way, the artist brings the past into contact with the present, which is one of the typical characteristics of contemporary Chinese artists.

Zhou Chunya (born 1955) also started his artistic career inspired by calligraphy, after having combined his China-based art studies with his experience at the Kassel Academy in Germany. A couple of years after his graduation, Zhou adopted a German Shepherd puppy, which soon began to feature in his paintings. He gained quite a bit of fame with this Green dog series. As Shao Fan did with his rabbits, Zhou was very close to his dog and the paintings are often interpreted as a metaphorical self-portrait of the artist. For me, it is the color of the depicted dog that stands out. Its jade-green color reminds me of the precious mineral that is found in China and reworked into jewelry. The German Shepperd might refer to his time spent in Europe.

Just as he was moved by the dog, Zhou turned towards peach blossoms, a natural phenomenon very much appreciated in Southeast Asia. The real beauty of the blossoms only lasts a couple of days in springtime, and so Zhou tries to stretch this time by leaving the open blossoms on his canvasses, free from being withered. The color of the blossoms is as striking as the flashy color of the dogs. As a Chinese artist referring to tradition, Zhou quotes a Chinese proverb that says: ‘The greatest truth lies in simplicity.”

Another Chinese tradition is fireworks. In fact, it was invented at some point between the 7th and 10th centuries. Originally, they were used in religious events to expel evil spirits. The ritual of setting off fireworks is therefore a permanent part of Chinese culture and is still associated with many festivals to this day. Fireworks can be very beautiful to watch for enthusiasts, but what does it have to do with art? It may surprise you, but the artist Cai Guo-Qiang uses it to create his works. The process is impressive to see and that is why Cai involves the public. A striking example of his firework-based art is to be seen in the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. The museum invited the artist to complete the work Odyssey for a live audience (it was also streamed live).

In a shed, Cai and his assistants processed 42 panels with cut-out templates. After the preparations, the artist spread gunpowder over the panels and lit the wick. The work caught fire and the audience witnessed a real firework on the laid-down panels. Gunpowder burned into the work in such a way that it shaped a traditional 13th-century Chinese landscape, in which a series of topographical elements alternate and a Feng Shui energy flow is considered. The panels currently occupy an entire room of the museum, and the visitor is guided through the landscape by dark tropical plants, palm trees and misty mountain tops that eventually crash down to a rugged coastline. A closer look reveals the various gunpowder effects, but it is the subtle reflection of the landscape on the polished black granite floor (as a dark pool of water) that makes a walk in this gallery a sacral experience. The sequence of the elements of nature has been placed according to the rules of Feng Shui, whereby the monumental mountains in the north of the gallery and the waterscape in the south contribute to a positive chi.

A nice fact is that Cai served as Director of Visual and Special Effects for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Fireworks guaranteed!

Several Chinese artists are nowadays openly talking about their griefs of (former) government policy. That has not always been the case. During Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution (1966–76), a culture of censorship prevailed: art academies were closed, artists were closely monitored, and many works of art were even destroyed by the authorities. The year 1989 was a turning point with the student uprising in Tiananmen Square, where the government had deployed tanks to contain the crowd. We all know the famous picture where a young student stops a series of tanks and thus symbolizes the everyday man who resists the giant of government; a modern David and Goliath. Since then, artists went underground and finally came to the public with their work around the turn of the century.

Contemporary artists such as Shao Fan and Zhou Chunya, who we listed above, come from families that have given the Mao regime a creative expression. Their parents were assigned to paint Maoist propaganda during the Cultural Revolution. Later, when they became artists themselves, this called for a reaction.

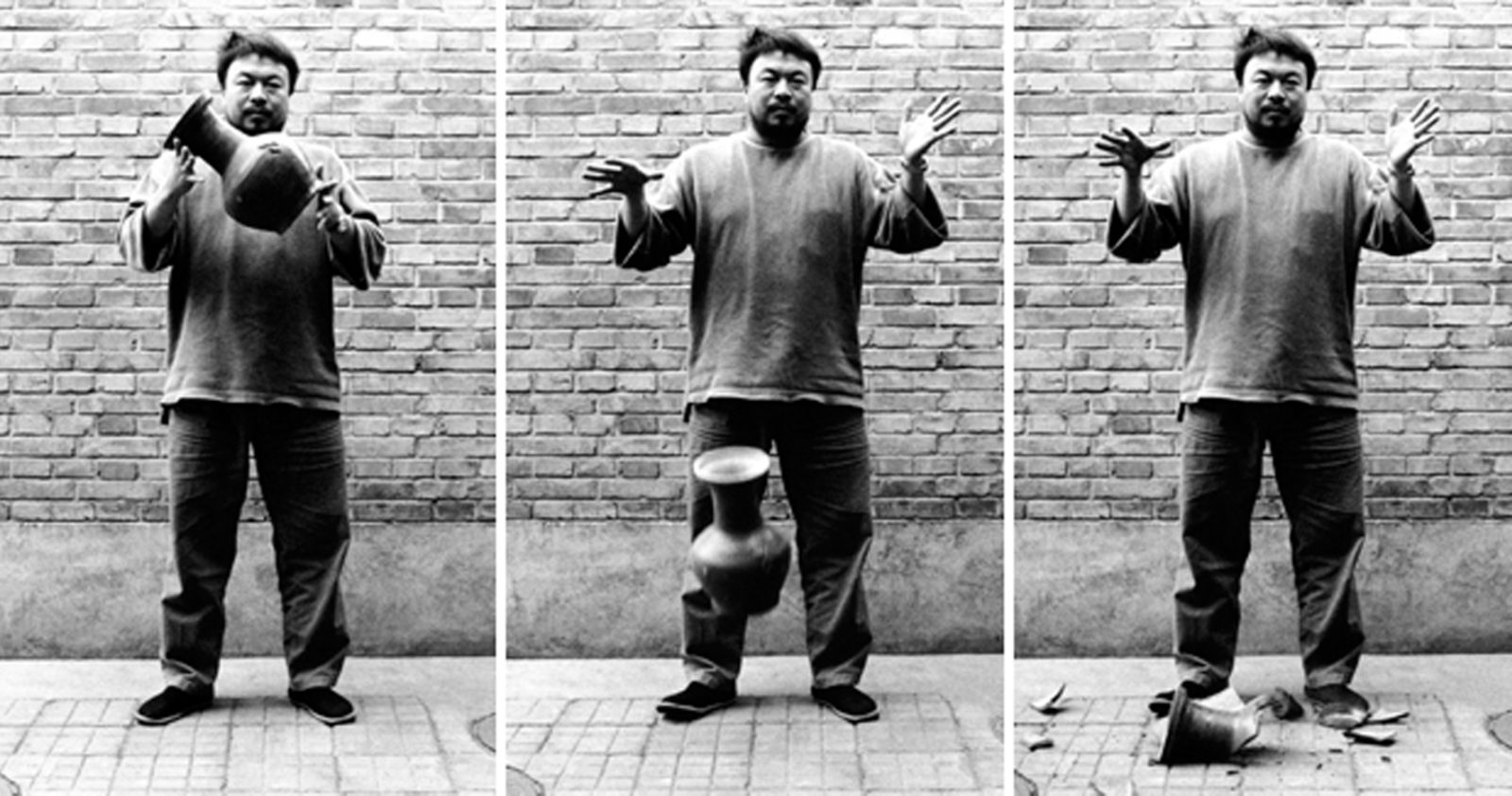

When you think of China and revolutionary art, the first thing that comes to mind is Ai Wei Wei, the artist who has made his dissatisfaction with the Chinese government his life’s work. He responds to the social and cultural changes in his native country, such as human rights, economic exploitation, and environmental pollution. Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn is a perfect illustration of his entire oeuvre. By dropping the 2000-year-old urn, Ai refers to the widespread destruction of antiquities during the Cultural Revolution. Mao Zedong had planned to build a new society and therefore old customs, habits, culture, and ideas had to be destroyed.

The destruction of this piece of art is displayed in a series of three black and white photographs which show Ai dropping the urn. It became a very controversial work: if he wanted to critique the government’s cultural policy, why did he smash the antique urn? Isn’t that the same as what Mao did? It enraged most antique collectors, but Ai’s aim was to remind them about heritage loss. Even today opinions are divided, but one must admit that the urn was blessed with a second meaning: it went from being a purely historical artifact to one of the most relevant symbols against the Maoist rage defacing the cultural heritage of China.

Furthermore, it has not been proved that Ai dropped an authentic antique; some say that it might be a fake. But I think that wouldn’t make any sense for the artist. On the contrary, Ai even claims that he smashed two antique urns in the process of creating the artwork because the photographer was not able to capture the dropping of the first urn.

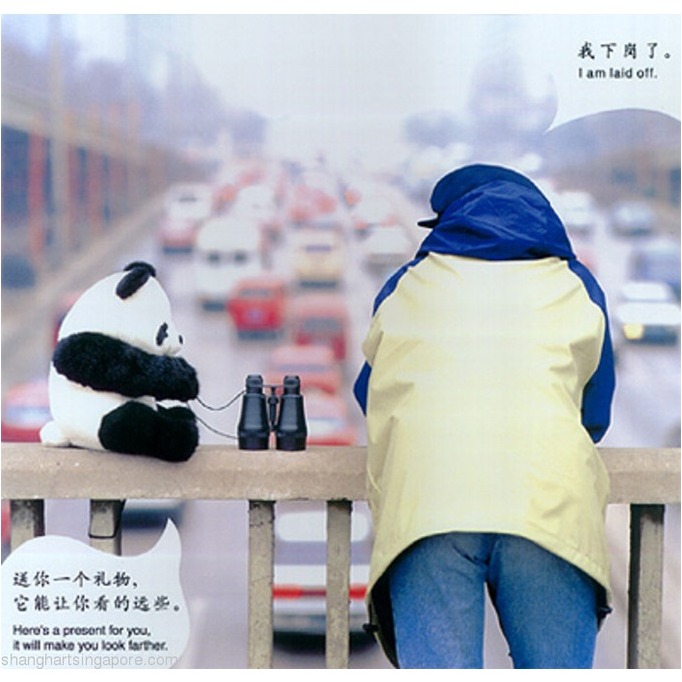

Zhao Bandi also criticizes the government in his work, although this is rather implicit. He achieved fame in the late 1990s with his “Panda series”. Zhao uses the animal, which is a symbol for China, to draw attention to social and political abuses. In Zhao’s manipulated photographs, the panda becomes a spokesperson who converses with the artist via text balloons on issues such as drug abuse, air pollution, violence, and unemployment, all subjects that suffer from government censure.

In China Lake C, Zhao refers to the strong control of the government. The young people, dressed in modern Western clothing, seem to have fun and be socializing on all kinds of topics. But appearances can be deceptive because if you look closer at the painting, you see that the young people are up to their knees in water. With this, Zhao shows that in addition to a relative freedom, there is always a certain inconvenience. It is a painting, but it could just as well have been a performance.

The government’s strong control over the Chinese population meant that the individual was absorbed into a unity that was easier to control. Collectivism is an inherent part of Chinese social history. The painter Zhang Xiaogang draws inspiration for his work from this and started in 1993 with the series Bloodline, the Big Family. This series consists of several hundred portraits, painted in a style very typical of Zhang. He based his work on family portraits from the time of the Cultural Revolution, which makes the subjects portrayed look very homogeneous. Their faces lack any emotion whatsoever and they stare into the audience as if they couldn’t care less. But that’s only at first sight.

At a second glance, you might recognize turbulent emotions and you might even say that body and soul are separated from each other. In many of Zhang’s paintings, a small part of the left half of the head has been given a different color. These areas can be interpreted in different ways: they give the depicted persons something personal, which is totally contrary to social values. In his technique, he also gives the depicted people a personality by painting a lightening effect on the face, as if the person is seen as a real (bright) individual, rather than as a part of Chinese society. The people also come out better thanks to the flat indistinctive backgrounds.

In this way the artist criticizes collectivism, but at the same time, he exposes the one-child policy. It was introduced by the Chinese government in 1979 (a two-child policy has been in place in China since 2015). This population policy meant that each couple could only have one child; having a second child was against the law (though exceptions were made). The purpose of this law was to decrease the population (China had previously suffered several famines).

The artist Song Dong is concerned with the influence of globalization and the lightning-fast modernization that his home country has undergone in recent decades. The 4.5-meter high by 9-meter-long installation Through the Wall is made of dozens of doors and frames from the old walled Hutong neighborhood in Beijing. This historic neighborhood, where Song himself grew up and still lives, has been steadily demolished in favor of new constructions since the 1990s. Just as he and his parents had to make ends meet with what was available during the Maoist board, he now uses found objects to realize his work.

The installation is surprising: along the outside, Through the Wall appears to be an impenetrable wall, but a small detour around the work brings you to a door on the side that gives access to a space that at first sight is hidden for the spectator. Behind this door, a room unfolds with mounted mirrors on the floor and the walls, in which not only the hundreds of different lamps on the ceiling are reflected, but the visitor’s own appearance is endlessly reflected in the work. It is a way of involving the visitor in recent events in China.

The 32-year-old He Xiang Yu has his own vision of the economic leap that China has made in recent decades. In his work The Tank Project, he shows a gigantic leather tank (type T-34 Soviet tank) from which the air has run out. It was quite an undertaking to realize the project. The jacket was hand-sewn by a team of 35 people for two years. The finished work consists of 400 pieces of cow leather and weighs over 2 tons.

Upon seeing this deflated tank, my thoughts go straight back to the student protests in Tiananmen Square, but that appears not to have been the intention of the artist. The tank is rather a symbol of the current economic wars led by the country’s businesses. China has conquered much of the luxury items market. After the market was first flooded with counterfeit products, nowadays high-quality products are also produced here. The expensive Italian leather refers in this case to expensive Gucci handbags.

The tank is accompanied by drawings and plans for its creation. Because military information is not available in China, the artist had to find assistants who were willing to sneak into an army base in the middle of the night to measure by hand the dimensions of the tank. Making art is still a risky business!

To conclude, contemporary art in China is a hot topic and is based on tradition and government criticism. That makes it very delicate and sensitive, but on the other hand also harsh, and it is often a balancing act between artistic freedom and government censorship. That was certainly the case in the 20th century, but fortunately, nowadays government policy is more flexible.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!