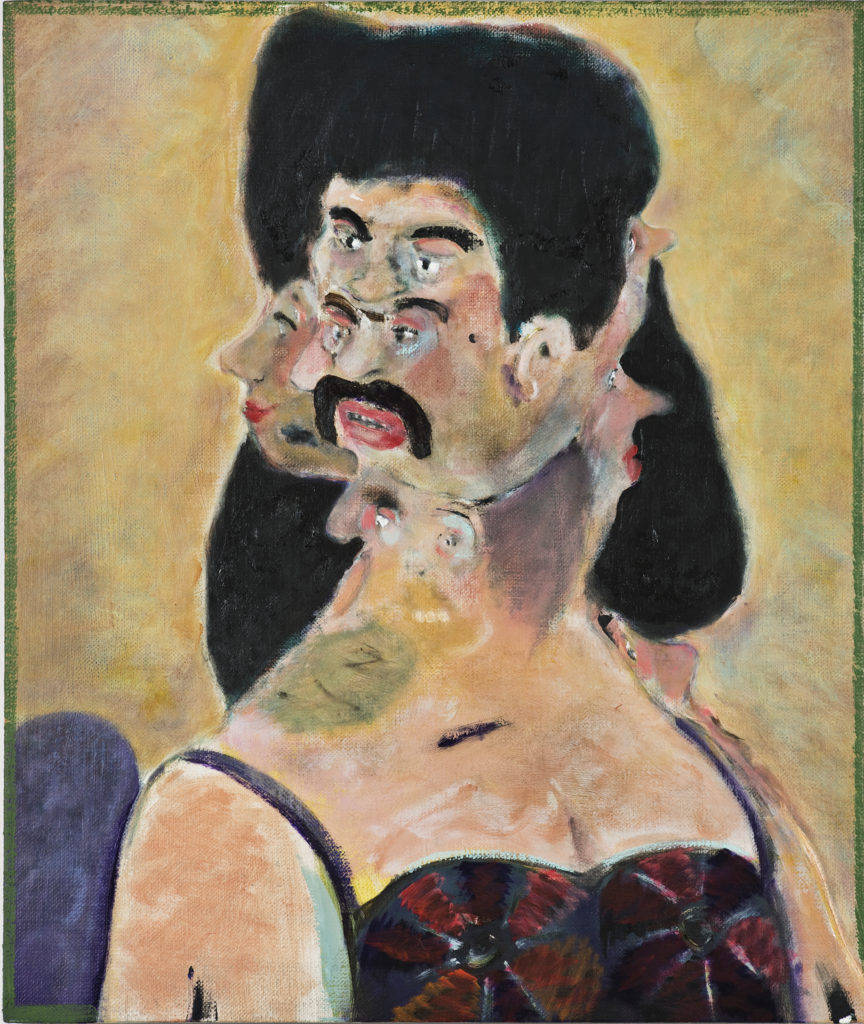

In Whitechapel Gallery’s Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium, ten of today’s key figurative painters use historical art influences to tackle critical contemporary issues.

Through a total of 40 canvases created over the last two decades, Cecily Brown, Daniel Richter, Sanya Kantarovsky, Tala Madani, Michael Armitage, Nicole Eisenman, Dana Schutz, Ryan Mosley, Christina Quarles, and Tschabalala Self experiment with depictions of the body. Bonded by this theme, each artist uses the body as a vehicle to reflect, explore, or challenge wider social issues. Although grounded in our current social moment, each work is in dialogue with its historical art predecessors – using recognized attributes and figures, or often directly referencing a specific artist or artwork, to shape new meaning in a digital age. In a generation with the world at its fingertips and constantly viewing instantaneous images via social media, Radical Figures places emphasis on the slow nature of painting. Highlighting its flexibility to warp, fragment, and subvert a figure, the artists similarly morph their art historical influences with the likes of contemporary news stories, children’s books, popular music, and pornography to form new narratives.

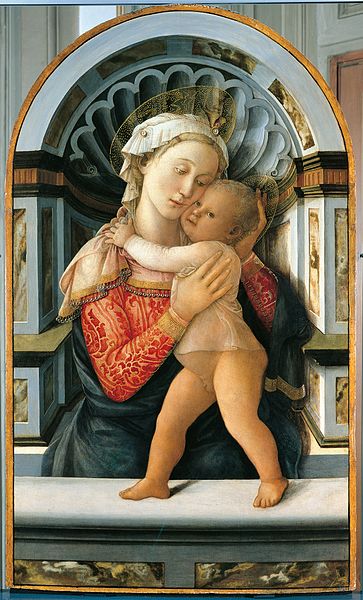

Sanya Kantarovsky’s Letdown (2017)

Inspiration: The Madonna and Child – one of the most central icons in Christian art history

Where’s the Influence?: Depicting a mother carrying her infant on her back, the weight of motherhood is emphasized in contrast to the doting Mary figure.

Rather than the rich golds, reds, and blues typically found in Madonna-and-Child paintings, Kantarovsky uses a cold palette in depicting his mother character. The mother’s grey-blue body seems almost skeletal and wasting, with the only accent to her appearance being the blood red grazes on her knees, legs, elbows, and nipples; this particular sensitivity alludes to the painting’s title, as Kantarovsky plays on the double entendre of the phrase ‘letdown’ – referencing both the process of releasing milk when breastfeeding and the word meaning disappointment. Both concepts, paired with the rawness of the mother’s wounds in the image, subvert idealized depictions of motherhood in art history, alluding to both the rarely spoken physical toll of being a mother and the social issues that can accompany it. The mother and child are seemingly alone in the wilderness, potentially letdown by a father figure, the welfare system, or another societal neglect.

Rather than having her head encircled by a faint, golden halo as the Virgin Mary is usually depicted, the mother raises her hands in a praying motion to a dull yellow light. Far from a holy idol, an opposing powerlessness or lack of control comes from the gesture, as if begging for relief. Letdown elicits an emotional response from the viewer, with the ambiguity of the title leaving room to question what shortcomings could have impacted these characters; whilst they seem timeless, with no clothes or attributes to mark them of a specific era, the piece turns focus away from historically idyllic depictions of mother and child to shed light on the sheer survival that motherhood often comes to represent.

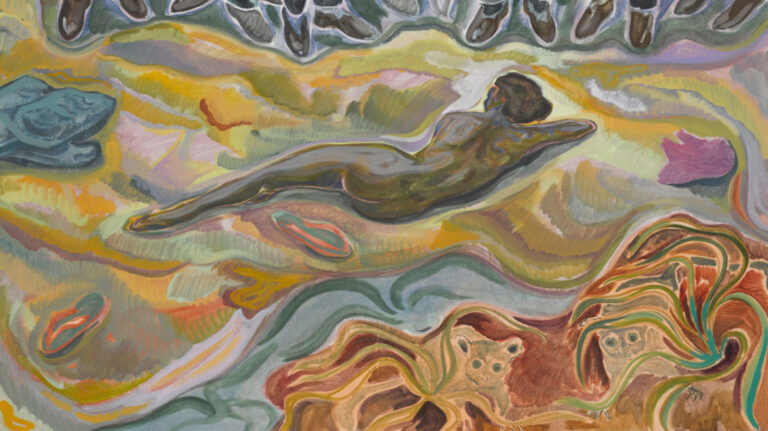

Michael Armitage’s #mydressmychoice (2015)

Inspiration: Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus

Where’s the Influence?: Echoing Diego Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus, Michael Armitage re-contextualizes the composition in reflection of a 2014 campaign originating in Nairobi.

Referencing the campaign in the title of the work, #mydressmychoice was a trending hashtag in protest of an attack on a woman who was publicly assaulted for wearing a miniskirt. Inspired by the news story, Armitage subverts Velázquez’s Venus – the reclining goddess of love who gazes at her reflection in Cupid’s mirror – altering the piece’s elements and positioning it in our current moment. As Cupid’s mirror becomes many pairs of men’s shoes pointing towards her, a faceless male gaze consumes the naked Venus figure; the female’s image is reflected in their perception, rather than her own, emphasizing her lack of agency in both the image and the wider social context.

With her clothes and the shoes strewn around her, #mydressmychoice becomes firmly rooted in its contemporary context and alludes to the misogynist act it is inspired by. Rather than the goddess of love, beauty, prosperity, victory, and fertility, Venus becomes a victim of abuse, degradation, and injustice in an oppressive society. Whilst the idealized Venus is adored by viewers, her real life reflection is subject to acts of hatred, leaving the viewer to consider the disparity between the two. Although Velázquez’s Venus is also subject to the male gaze, sensually positioned with her naked backside to the viewer, Armitage elevates this through his use of color and form. Stylistically influenced by Gauguin and Munch, the piece raises awareness of the news story that the hashtag originates. Simultaneously, an interesting parallel is drawn between the patriarchal systems to which the woman in the painting, as well as the female nude in art history, fall victim.

Dana Schutz’s New Legs (2003)

Inspiration: Francisco Goya’s Saturn

Where’s the Influence?: Using Goya’s piece which references the Roman myth of Saturn, who ate his children for fear of being overthrown by them, Schutz reflects the artistic process.

As the central figure is propped on a stand of rocks, it leans over in concentration of a sculpture – it is unclear whether this is a creation of new legs, or a sculpture made from its own. Much as with Saturn, a relationship is drawn between creation and destruction. Whilst Saturn eats his own offspring, the artist metaphorically chops off a part of themselves to channel into creation, using their own experience, pain or feeling as means of expression. The artistic process is further depicted as raw, implied by the redness of the figure’s limbs in relation to the pink of its body, and cyclical: in an effort to build new legs, the figure becomes legless.

In contrast to Goya’s frenzied Saturn, Schutz’s figure is composed and concentrated, carefully molding its creation as birds fly overhead. Although both pieces are in direct conversation, New Legs appropriates Goya’s graphic piece in a German Expressionist style, subverting a depiction of male power and obsession to her personal artistic struggle. Despite apparent differences in style, both works are bonded by a mixture of self-sabotage and productive interest, as Schutz uses Goya’s work to create a parallel between children and parents, artists, and their artwork.

Nicole Eisenman’s Progress: Real and Imagined (2006)

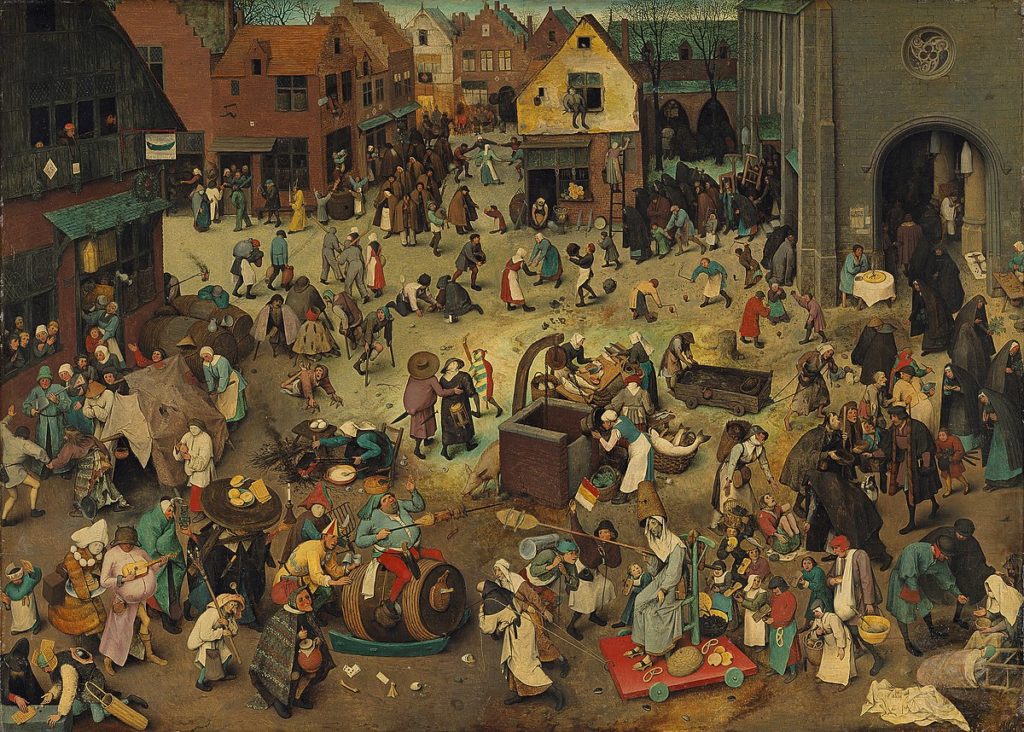

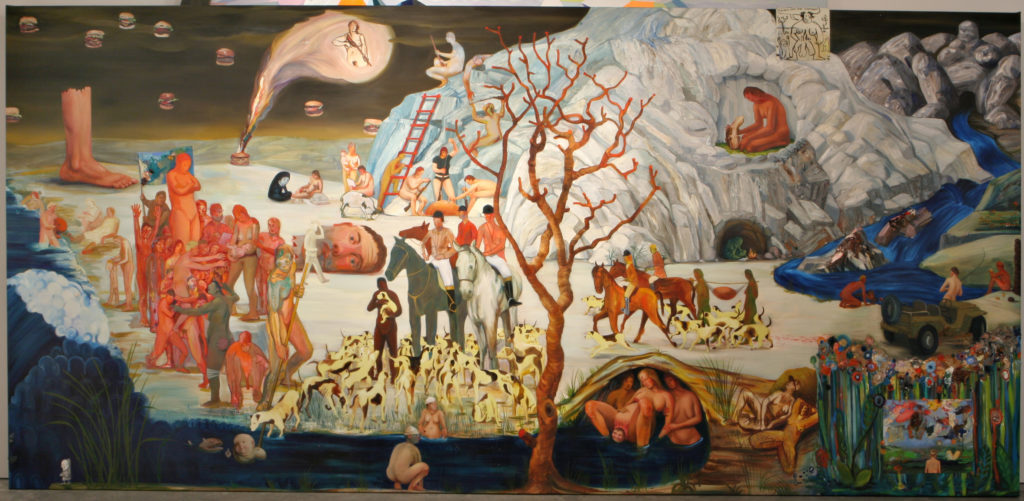

Inspiration: The acute detail of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel

Where’s the Influence?: In the detailed style of Bosch or Brueghel, each of Eisenman’s panels first appear to treat a different subject. In the most narrative of the two, the left panel depicts an artist in a boat-like studio. Crouched over in the claustrophobic space, the artist is enshrouded by various objects, such as loose paper, paintings and paint. Implied in a thick, impasto fashion, the application of paint elevates the painting past its traditional influences, exploring texture and depth in a contemporary way.

The grappling with art historical influence and the desire to create something new can also be seen, with typical landscapes and portraits surrounding the artist as if an index of ideas and influences spilling from their head. Adding to the sense of flurry and chaos, two sailor figures grapple an ore whilst separated by the walls of the room; this heightens the sense of struggle, depicting the push and pull of artistic creation as we both rebel against, yet are in constant dialogue with, the past. Against tumultuous tides, water seeps into the left side of the boat, possibly representing the pressure time inflicts on the artistic process.

Connecting the two paintings, the waves spill into the right hand panel, which presents a detailed scene on a different scale. Riffing off of the surreal elements of Bosch’s works, such as Christ in Limbo (1575), Eisenman represents life and death amongst various contemporary elements. Whilst depicting naked, primitive figures like those of Bosch, Eisenman also features a car and various floating burgers, merging early representations of civilization with tokens of today’s society. Production is a key theme in the piece, as biological reproduction is positioned in contrast with food production, signifying the consumer culture of the 21st century.

Linking to the left-hand panel, artistic creation is translated into procreation through various images of birth and babies. Depictions of armed women, a beheaded male and ghoulish creatures juxtapose creation imagery; either a creation story or an apocalypse, destruction is never far from production in a similar vein to Schutz’s New Legs. Against many female figures, the beheaded male may also reflect the struggle for female artistic representation in the cannon; whilst there are vast representations of birth, five of Eisenman’s women are armed with guns in a possible rally against patriarchal values. In Progress: Real and Imagined, women are producers of both life and art, subverting art historical traditions and placing them at the forefront of creativity.

The range of issues and topics raised in Radical Figures is vast, with different artistic viewpoints coming together to voice the shortcomings of today’s society. Nodding to the past whilst looking forward to the future, each artist uses art history as a springboard from which we can ultimately learn from; whether through iconography, composition, style, and most importantly, subversion.

Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium is at Whitechapel Gallery, London, from 6 February – 10 May 2020.