Akhenaten: Artistic Development in the Amarna Period

Amenhotep IV, widely recognized as the notorious Akhenaten, was the enigmatic “heretic” pharaoh who ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty.

Maya M. Tola 20 July 2023

14 January 2021 min Read

For the first time since 1986, the Nadler Collection will be shown to the public in the exhibition Modernism Foretold: The Nadler Collection of Late Antique Art from Egypt at the Georgia Museum until the 26th of September 2021. We interviewed the curator of the exhibition, professor Asen Kirin.

We’re here to learn why we should talk about ‘Late Antique Art from Egypt’, rather than ‘Coptic Art’, about the history and importance of the Nadler Collection in our time, as well as the authentication and repatriation issues in the field of art history. Kirin also underlined a very interesting connection between Egyptian Late Antique Art with 20th century Modernism.

Asen Kirin is Parker Curator of Russian Art and professor at Lamar Dodd School of Art, University of Georgia; with his experience and competence, he helped us understand a very complex, multifaced, and yet very important part of art history that is often underestimated by the broader audience.

What are the key elements of Coptic Art?

The term itself, “Coptic Art”, states that this is the art of the Copts, who are the Native Egyptians living in North Africa in the territory of Egypt, who speak a language related to the language of the Ancient Egyptians; and the majority of this people confess Eastern Orthodoxy, so they are Christians. The term Coptic applies to them, and this is the art that was created by Copts or commissioned by Copts to be used in their lives and worship. The Native Egyptians for centuries have lived under various, different rules: in the 4th century BCE, with the conquest of Alexander the Great, there was Greek rule in Egypt, which was then followed by Roman rule, followed by Persian rule, then the Byzantines succeeded, and finally, in the 7th century the Arabic conquest established the situation that is very much in place now, where there is an Arabic-Islamic majority living in Egypt. So Coptic Art was created by and for the Native Copts, but now in the last three decades experts are avoiding the term Coptic Art, and instead, they favor a different term, namely the Late Antique Art from Egypt, and this is the term we are using consistently in the catalog and all materials associated with our exhibition.

Why did the term change?

The change reflects a new understanding of the complexity of the culture in Egypt during the Late Antique period. So, when one says Late Antique Art from Egypt, then one includes the Copts, who are a very important part of the society during late antiquity, but also the Greek-speaking members of the society, the Latin-speaking Romans who lived in Egypt. It is an inclusive term that now we consistently use to emphasize the fact that the society in Egypt between the 3rd and the 7th century was very multiethnic, multicultural, and the different groups that formed this society in equal measures contributed to the flourishing of the arts. This is a very complicated explanation, but it is a necessary one, and that is one of the reasons why the Late Antique period from Egypt is so relevant in our own time, of a global society with very obvious multiethnic, multilingual and multireligious components.

So, what kind of art is it?

The majority of the arts that survived comes from burial sites. One of the reasons why we have such remarkable items used in burials or to decorate monumental tombs is that the climate in Egypt, which is very dry, allowed for otherwise perishable objects made of textile, or wood, to survive. And so we have a great number of textiles from the 3rd to the 7th and 8th century CE; we have objects made of wood, of bone, and finally, we have a great number of works of stone: the majority of those are reliefs, but also there are sculptures in the round. Most of these sculptures were used for the decoration of elaborate tombs, and there is of course architectural sculpture: these are the cornices, the entablatures, of course, the capitals of large buildings, very often churches.

This is an obscure topic by comparison to other major periods in the history of art, but what is so relevant about the Late Antique Art of Egypt, formerly known as Coptic Art, is that when this art was discovered and Western scholars started studying and understanding it better, they realized that this art looked like a precursor of modernism. It looked like it was foreshadowing the important developments that would occur in Western art between the end of the 19th century and the very beginning of the 20th. And all of a sudden, shortly after this discovery, Coptic Art became very fashionable: every European museum wished to have a collection of Coptic Art, the market of Coptic Art thrived, and the same thing happened after the end of World War II. The art market just boomed: private collectors and the major museums in the world were acquiring works of Coptic Art in great numbers. And the reason for this was precisely this keen awareness that during the Late Antique period in Egypt the art that was created presaged modernism.

And what is the connection between Late Antique art from Egypt and the cultural identity of this country?

There are different phases in the history of this phenomenon, but with the emergence of Coptic Art studies the dominant view was not that this was the art created by Greeks and Latin-speaking Romans, and maybe Nubians who lived in Egypt, and Copts. From the late 19th century all the way into the 1970s and 1980s the dominant view was that this was the art of the Copts and that it was folk art. Until the 1980s, when with the rise of Late Antique studies things changed and the focus shifted, the idea was that this was the art of the poor working people of Egypt, of agricultural workers who created this art and used it. And there were very important claims made by this assertion: first that it’s purely Egyptian, so there were no Greeks and Latins involved; then that this is the art not of the ruling class, the establishment, but of the working people.

So the view is that this art embodies Egyptian cultural identity. But with the appreciation of this art across the world and with the accumulation of knowledge about Late Antique culture, it became obvious first of all that Greek-speaking citizens of the Roman Empire living in Egypt contributed a great deal, along with the Copts, with the Egyptian-speaking citizens, with the Romans, and the Nubians as well. So, it became impossible to continue using the term Coptic because the notion of what is Late Antique Egyptian identity changed: it’s not purely Egyptian, but multicultural. Of course, the development of Late Antique studies is the main intellectual current that contributed to this title change.

Could you show us the connection between Late Antique Art from Egypt and modernism using an object from the Nadler Collection?

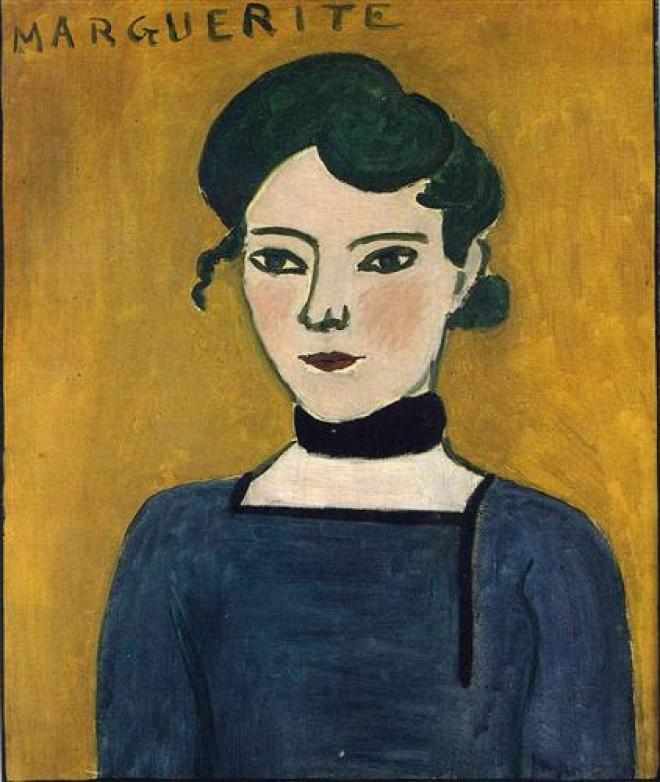

Several Coptic textiles were parts of tunics: these are tapestry weave sections of elaborate tunics that survived from burials. Here is a bust of a lady: she could be a pagan goddess or a distinguished lady from antiquity. But look at the similarity between this Egyptian lady and the portrait by Matisse of his daughter Marguerite. Look at the eyes, the rendition of the nose, the very small mouth tightly closed rendered with very pungent red. This is why everybody believed the great artists of the late 19th and early 20th century became very enamored by the works of Coptic Art because they saw them as the historic precedents for the aesthetic experiments and values that they treasured.

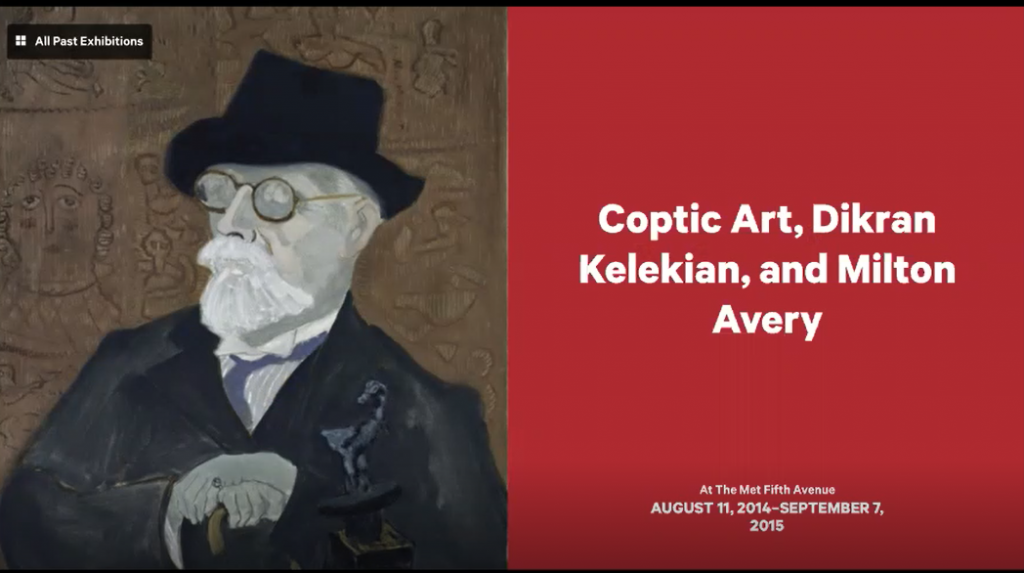

Another example is a poster of an exhibition of the Metropolitan Museum: in 2015 the Met organized a show dedicated to the connection between one of the great American modernists, Milton Avery, and a particular famous dealer of Islamic and Near Eastern art, Dikran Kelekian: he was a gallerist of great international standing who had galleries in Cairo, in Paris, in London, and New York, and at the turn of the century he was the greatest dealer of Islamic art, but he also dealt with Coptic art and he made such a leading figure of American modernism as Milton Avery appreciate Coptic art. And you can see how in the portrait of Kelekian, an Armenian gentleman from the Ottoman empire originally, he is rendered in front of a large Coptic tapestry.

Another example is the relief of Leda and the Swan, one of the most important works of the Nadler Collection; from the point of view of a contemporary observer it is almost comical: Leda is not a graceful seductress, in a traditional sense of this word, but she is very expressive, and this kind of rendition of the human body is so profoundly modernist. You can think about the works of Matisse, like La Danse, but also of Picasso, and Braque. What is so striking is that during the Antiquity and Late Antiquity subjects related to classical mythology were rendered in a style that adhered to high traditions of Greco-Roman art. These are two examples of ancient sculptures showing Leda and the swan but look at the difference of the rendition. So it’s this expressiveness that we find in the Nadler relief and only in other three or four similar reliefs that are well preserved and well known. That is an example of how and why modernists considered that Coptic art was foretelling their accomplishments.

Let’s talk about the beginning of the Nadler Collection: how and why did Maurice Nadler start collecting this kind of art?

Maurice Nadler was the first member of the Nadler family to arrive in Egypt in an attempt to establish himself there: so there is this element of a newcomer to an ancient country, to a thriving cosmopolitan city that is an international business center. He arrived in Alexandria and he had talents, he was a polyglot who spoke 7 or 8 languages: that made it possible for him to establish his very successful business and then within just a few years he became a prominent member of the business community in Egypt. He had immense wealth, but he was a newcomer, and then he discovered that many major figures in history, even rulers and emperors, like Catherine the Great, legitimized their prominent place in society by collecting art and making their art collections speak about their values.

When Maurice Nadler started collecting art he did not separate pharaonic Egyptian art from the Late Antique one: he collected both because by the time he started collecting there was a very clear notion formed inside and outside Egypt among art lovers and scholars that there was continuity between these two periods in the history of art. So for Maurice Nadler, it was essential to assert his newly gained social prominence in the cosmopolitan business world of Alexandria, by showing that he embraced and celebrated the culture of his newly adopted country. But it was also meaningful to him apparently because he was a very devoted collector, and he invested a great deal of his wealth into forming this collection.

Where did the collection start?

He started collecting in Alexandria but at that time, in the 1920s, Berlin was a major center of scholarship related to Egypt: egyptologists worked for the major museums and the universities, and the most prominent art dealers who sold Pharaonic and Coptic art were there too. So he then set himself in Berlin to pursue his collecting on a higher level. Maurice Nadler showed everybody that he had embraced the culture of Egypt; he wanted to prove to everybody that his prominence in the business circle of Alexandria was not superficial. And he also felt an enlightened modern man by appreciating the arts coming from Egypt, in the context in which this art was viewed in the early 20th century as an important historic precedent of current modernist development.

Did Maurice’s entrepreneurial spirit have a part in this?

Of course; a possible inspiration for him was a famous Jewish German industrialist, but businessmen or families collecting art were everywhere: the Krupp family in Germany for example, but also in America the Henry Clay Frick and J. P. Morgan Collections, among several others. Famous businessmen became art collectors and changed the history of art collecting. Maurice Nadler modeled himself on these prestigious examples. He intended his home in Alexandria, Villa Nadler, to become a museum.

What about the issue of authentication of these works of art?

The field of Coptic art, using the traditional term, has gone through a sobering phase of reassessment that started in the 1970s and continued through the next decades all the way to our own time. This reassessment had to do with the realization of experts that many works of Coptic art found not only in private collections but also in the major museums of the world, displayed either traces of later modern interventions or they were entirely a product of artisans and artists working in the 20th century. These were works made for the booming market: when the market demands suppliers find a way to deliver and so there are many questionable works.

The right attitude of curators and experts is very clear: if there a doubt about later intervention or the originality of the works then this is admitted and discussed, and there is a great deal of knowledge to gain from this process. Then when you find out what are the works that are not fully authentic: are there features that connect them? What comes across is very obvious: the exaggerated features that can be associated with modernism are regularly found in these not fully authentic works.

Another feature that is very often found is the proliferation of Christian symbols. This is what the market demanded, and why the market was demanding this is an interesting issue. But this is how the field moves forward and what is so important about seeing the Nadler collection again after decades is that the last time the collection was on display all these questions were bubbling but were not dominant in the field. Since 1980 scholars spent a great deal of effort discussing the questions of authenticity, and now the Nadler Collection is reintroduced to the public in a new different phase in the history of the discipline, so the reassessment of these works can start anew. It’s very reassuring because you can see that there are fully authentic works that contributed a great deal to the conversation, and we acknowledged that some works may have been retouched.

It is important to also show the works that have been retouched or that are not fully original, as they are also part of this history.

Exactly, this is a very important point that you are making, and I hope that our show makes it explicitly clear because this is how the conversation moves forward and how we gain additional knowledge about different practices in the field of trading and making of antiquities, but also in the perception of Late Antique art. The shifts in perception of Late Antique art are reflected in the manipulation of original works or the creation of imitations if we are to use a more polite word than “forgery”.

The collection is now in Georgia, in the United States, but would repatriation be right in this case?

The question of repatriation doesn’t really apply to the Nadler Collection because repatriation is usually an urgent issue when it comes to works of art that were found in collections around the world as a result of the illicit trades with antiquities. The international regulations that govern this field have to do with a very important document generated by UNESCO in 1970 and ratified by most of the members in the following two years; the United States ratified this convention in 1972. This is the cut-off year; when artifacts of significant historic and aesthetic value are discussed with regards to sending them back to their country of origin, the year 1970, or in the United States 1972, is to be taken into account. If the work of art came to the United States after 1972 then it is a subject of study, consideration, and potentially repatriation if proven that it had to do with the illegal trade of antiquities.

The Nadler Collection is a unique example of how an entire collection of art can be shown and displayed without substantial worries concerning claims for repatriation because the collection remained in the family, between the people who formed it. The collection was formed between 1920 and 1941 in Egypt and mostly in Berlin; then it was taken out of Egypt legally in 1952 and kept in Lausanne for safekeeping until 1960 when it was shipped from Switzerland to New York City because the family was relocating. Pauline Nadler, Maurice Nadler’s widow, is the one who shipped the collection from Alexandria to Lausanne and then from Lausanne to New York City. So the collection arrived in the US 12 years before 1972, and it was not sold or dispersed, or acquired at that time, and the last purchase was in 1941. This is what makes the collection such a rare example of works of art from late antiquity with very secure provenance. We don’t know exactly what the specific sites from where these objects come are, but we have very clear documentation that once they entered Nadler Collection they were not traded, or acquired after 1941 and that the shipping out of Egypt was legal and took place very way before the cut-off date.

What is the future of the collection?

Now, the collection remains a property of the Nadler family: it is entirely within their discretion to do what they wish. We can help: the objects are very fragile so they shouldn’t travel much, but theoretically, they can travel, and it is entirely Nadler’s decision. If I can express my personal view I would say that traveling the exhibition is an option, dispersing it by organizing an auction is also an option for the owners of the collection, but I would say that it would be such a loss not to have all these objects together in one place. And I say this with confidence because I studied the history of the collection and saw how much more we learn about this art and the history of art collecting as a cultural phenomenon having an assembly of objects gathered together by the same art lover and having them now still together with us. My personal opinion is that for the future generations, for the benefit of the field of art history and art collecting it will be so much better to keep the collection intact.

If you are in Georgia, we highly recommend visiting this exhibition. It is a unique opportunity to see a rare kind of a cohesive art collection and to discover more about Late Antique Art from Egypt. If you can’t go there, you can order the exhibition catalog here; you’ll find there a great essay written by Asen Kirin and the pictures and descriptions of every piece of the Nadler Collection.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!