The Exhibition

The exhibition is located at the Podium and extends across two floors. On the first floor, visitors will find seven themes divided by curved, towering plexiglass panels. Like transparent screens, these installations allow visitors to look through them to spot the diverse ornamental elements present. They also outline visually the various cultures that have gradually contributed to the aesthetic changes.

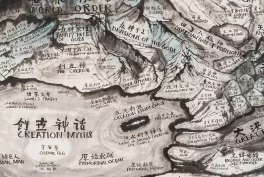

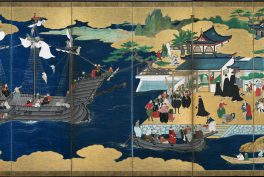

The journey begins with Readings, East and West, where visitors can marvel at ancient folding screens displayed in half-light to facilitate conservation. Visitors can look at these exhibits from left to right or vice versa. Either way, there will be a sense of traveling across time and space with the fluctuating landscapes and cartographies. Such an arrangement brings to the forefront themes of discovering new worlds and connecting with diverse cultures.

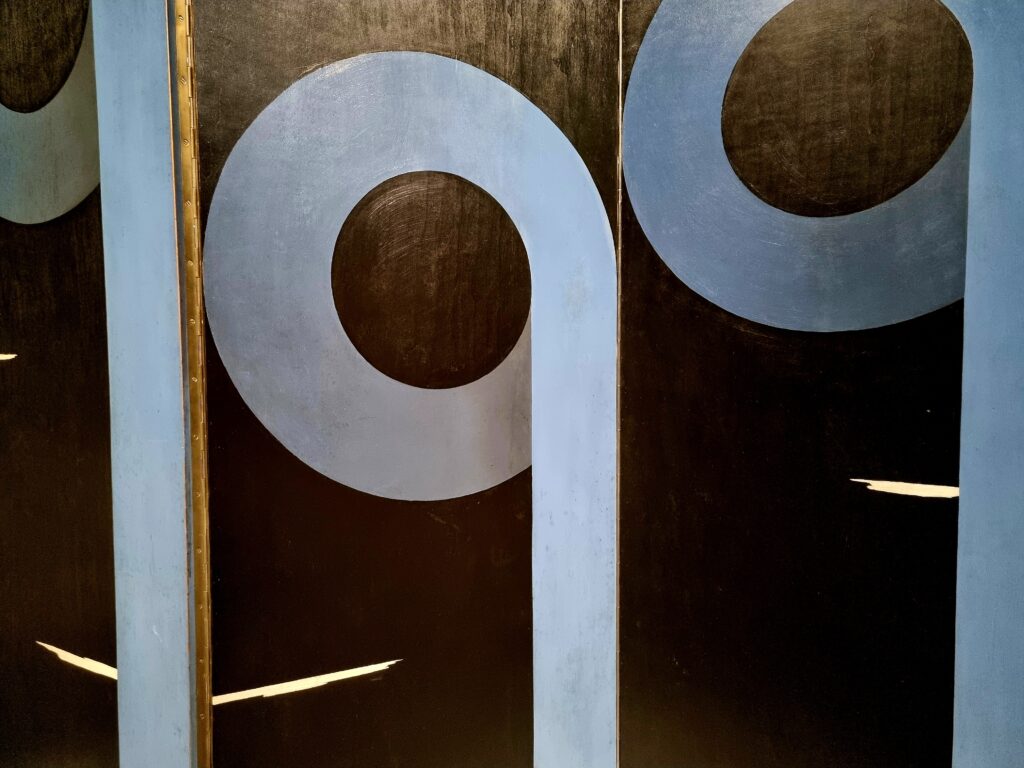

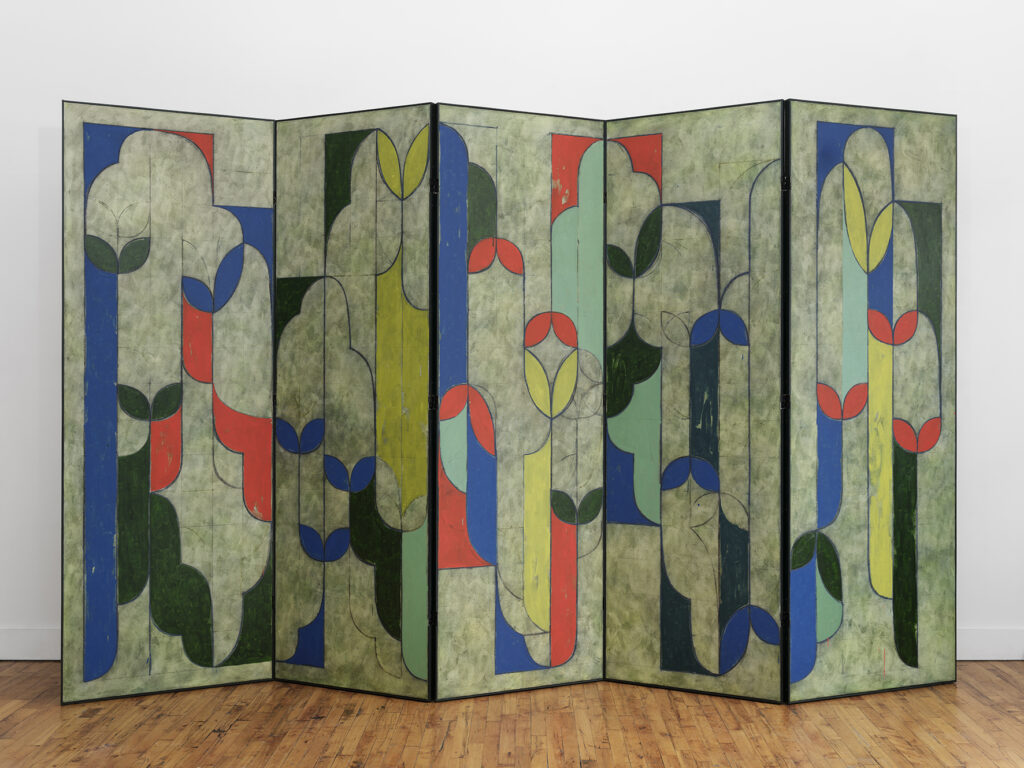

Continuing to the Public/Private section, the folding screens engage with topics of interiority and intimacy as they probe into the realm of private desire. Here, the exhibition includes the work of the American painter William N. Copley, which examines the segregation of genders and patriarchy. These apparatuses, as reflected in his work, reduce women to subordinate roles such as housewives or prostitutes. The vibrant colors and flattened renditions of female bodies convey the message with an abstract, somewhat comic-like touch.

This section also showcases the work of the South African painter Lisa Brice on an elongated, multiple-paneled screen that draws viewers into a potent feminist and somewhat claustrophobic space. Within this space, one sees women in motion and interacting with each other, and feels the collective strength and sense of independence exuding from it. The energized female figures serve to uphold freedom and everyone’s capacity to exercise such a right to the fullest.

The exhibition’s narratives then arrive at our present times epitomized by digitalism, conversing with the almost futuristic use of the paravento. We are walking through the Split Screens section. Here, the screen no longer serves solely as a shield. It also becomes a window, displaying digital projections of visual narratives from the outside world. Technical interventions showcase how digital immersion blends the imaginary with our day-to-day reality. It proceeds to prompt us visitors to ponder what the ubiquity of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and televisions could implicate as they become integral to our daily lives.

The liminal Four Seasons area is a niche for contemplating the passage of time and the change in space through the process of abstraction. Right next to it, through Propaganda, visitors are challenged to reflect on the rhetoric of politics. The World of Interiors segment inquires about the nature of art and the classification of everyday objects, including furniture. Can a folding screen, commonly found in households, be considered a work of art? Who or what defines the boundaries between “highbrow” and “popular” art?

A possible answer lies in Francis Bacon‘s dialectical Painted Screen. Despite its straightforward and minimalist appearance, the screen is groundbreaking due to its mundanity. It appears unassuming but thought-provoking to be both an everyday object and a work of art. The duality it inhabits is not irrelevant to how Bacon became an artist. He found his voice by studying his predecessors like De Chirico and Picasso. He discovered his form of expression using the religious three-panel painting format, or triptych and then promoted it among his contemporaries. With such an interplay between art movements and individual experiences, a composition like this folding screen can finally arrive as a piece of furniture in our homes.

Located on the ground level is another section called Parody/Paradox. It makes a pleasant contradiction out of surrealist and Dadaist screens interrogating the absurd. Notable contributions include the menacing grater designed by British-Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum.

A flight of stairs beckons visitors to the final hall of the exhibition. Along the doorway, Jean Prouvé‘s monumental screen signals a shift in perspective. Inspired by airplanes, this installation adapts an industrial aesthetic that gestures at the malleability of a screen both in dimensionality and in terms of its own materiality.

The final exhibition hall, titled Either/Or/Neither/Nor, comes as an upscaled game of dominoes, with screens in place of tiles. The title triggers questions for the visitor entering the room: Is the folding screen a piece of furniture? Or is it a sculpture? It is neither a piece of furniture nor a sculpture, or rather, it is both.

On the outside layers, visitors will find the oldest Chinese and Japanese pieces, while further inside are works from modernists such as Pablo Picasso, who incorporates colors and shapes reminiscent of late Cubism. Not far from it, the eclectic René Magritte departs from his typical style, presenting a tangible object featuring three reality-bending stylized figures that seem to be masking themselves when viewed from the other side.