Camille Claudel in 5 Sculptures

Camille Claudel was an outstanding 19th-century sculptress, a pupil and assistant to Auguste Rodin, and an artist suffering from mental problems. She...

Valeria Kumekina 24 July 2024

Latin American painters, sculptors, and printmakers were at the forefront of the aesthetic revolution that shook the 20th century. Until recently, male artists have been credited as leaders of Modernism from Mexico to Argentina. However, women Modernists in fact played a pioneering role across the Americas, producing pictures that were ground-breaking in subject matter and style.

They stood their ground against political dictatorships and racial discrimination, convinced that art could bring about social change. Most were native-born but a few were foreigners, attracted especially to the vibrant scene in Mexico. The name Frida Kahlo is widely known, but many of her peers also earned international reputations from the 1920s onward and helped carve out a permanent place for their gender in Latin America.

Latin American Women Modernists: Frida Kahlo, My Dress Hangs There, 1933, Hoover Gallery, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) has become one of the best-known artists in Mexico, topping her muralist husband Diego Rivera’s popularity. In many of her paintings she portrayed herself, often wearing Indigenous clothing. Her painting My Dress Hangs There uses a clever alternative to self-representation. Furthermore, it expresses her opinions about the United States, where she and Rivera lived for several years while he painted murals in New York, Detroit, and San Francisco. A picture of screen star Mae West (can you find her?) dripping Hollywood glamour contrasts with Frida’s handmade dress. The NY Stock Exchange at the center references capitalism. Meanwhile other icons of industrial society including a prominent toilet bowl suggest the sacrifice of human values to profit. Clearly, Kahlo did not like the US and wanted to return to Mexico!

Latin American Women Modernists: Tarsila do Amaral, Anthropophagy, 1929, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) is celebrated for her colorful expressions of national identity for modern Brazil. Beloved in her native country, a big exhibition shown in 2017-2018 at both New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Art Institute of Chicago spread her reputation internationally. Her upbringing on a coffee plantation provided insight into the life of the countryside and the diversity of the landscape in Brazil, a country larger than the United States.

Born two years before the end of slavery there (officially on May 13, 1888) she inserted the Afro-Brazilian body into her works. For example, her piece A Negra replaced the usual depiction of a white female nude with an oversized naked Black woman. She continued this practice of subverting European tradition in a picture titled Abaporu, which in the indigenous language of Tupí Guaraní means “man who eats people”. It inspired her then-husband the poet Oswald de Andrade to write the Manifesto of Anthropophagy, or Cannibalism. Here he explained that Brazilian modernists are like cannibals who consumed European art, transformed it, and made it their own; an apt description of Tarsila’s art as well.

Latin American Women Modernists: Julia Codesido, Vendedora ayacuchana, ca. 1927, Museo de Arte de Lima, Lima, Peru. Archivo Digital de Arte Peruan.

Julia Codesido (1883-1979) became a successful artist in Peru at a time when the country’s strong patriarchal values made it difficult for a woman to have any career outside the home. Fascinated by her native landscape, she painted many expressive scenes of the Andes. She also excelled at depicting the figure, challenging conventions by painting the female nude, which was rare in Peruvian art of her day. By the early 20th century, a movement was emerging called Indigenismo. It sought to bring Andean identity and the native or Indigenous people who had been marginalized for centuries to the center of national discourse. Codesido was in the lead of artists who portrayed Indigenous women, often situating them in an Andean setting. These pictures made visible this forgotten female population so that society and the government could no longer ignore them.

Latin American Women Modernists: Norah Borges, The Yellow Couch, 1961, Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes Rosa Galisteo de Rodriguez, Santa Fe, Argentina.

Being the sister of one of the most famous authors in 20th-century Latin America must have been challenging. However Leonor Fanny “Norah” Borges Acevedo (1901-1998) charted her own path as a visual artist. In both her native Argentina and in Spain, she created forceful illustrations for books by her brother Jorge Luis Borges. A key exhibition at Bellas Artes Museum in Buenos Aires in 2020 demonstrated that she was a key member of international avant-garde circles in the 1920s and contributed cover designs for magazines that circulated revolutionary ideas about art.

A quick glance at her oil paintings suggests intimate spaces occupied by women. Her sitters often hold a flower or a tamed bird and appear to conform to conventional feminine art. Looking more closely, we realize that these figures are staring off into space — disconnected and androgynous. They conceal her underlying message: these women dwell in a mysterious and disturbing world. A world that perhaps corresponds to the political and emotional upheaval she experienced (including imprisonment in 1948) in Europe and Latin America.

Latin American Women Modernists: Maria Izquierdo, Sorrowful Friday, 1944–1945, Museo Blaisten, Mexico City, Mexico.

María Izquierdo’s (1902-1955) distinctive contribution to Mexican art is her series of paintings from the 1940s capturing ofrendas, traditional altars found in many homes. She drew upon the familiar practice in which families laid out offerings such as food, flowers, or small trinkets for Easter, saints’ days, and Day of the Dead celebrations. Her colorful pictures represent a blending of Spanish colonial religious traditions and Modernist experimentation with space and form. Combining the domestic and the spiritual, she asserts the role that women play in the lives of everyday Mexicans.

Latin American Women Modernists: Amelia Peláez, Marpacífico (Hibiscus), 1943, Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC, USA. Gift of IBM © Amelia Peláez Foundation.

Amelia Peláez del Casal (1896-1968) merged Cuban domesticity and European Modernism in her life and art. Born into a family of some means in Havana, she received a conservative art education at the city’s San Alejandro Academy. She then moved to Paris, where she pursued more radical training with cubist painter Fernand Léger. By 1934, she was back in Havana, where she became active in developing the Cuban vanguard. In her artworks she applies the simplified shapes and multiple perspectives she learned from the French Cubists to details of her family home Villa Carmen (built in 1912). The vibrant stained glass, striking iron railing, ornate plasterwork, and exterior garden characteristic of Cuban architecture inspired many of her pictorial motifs.

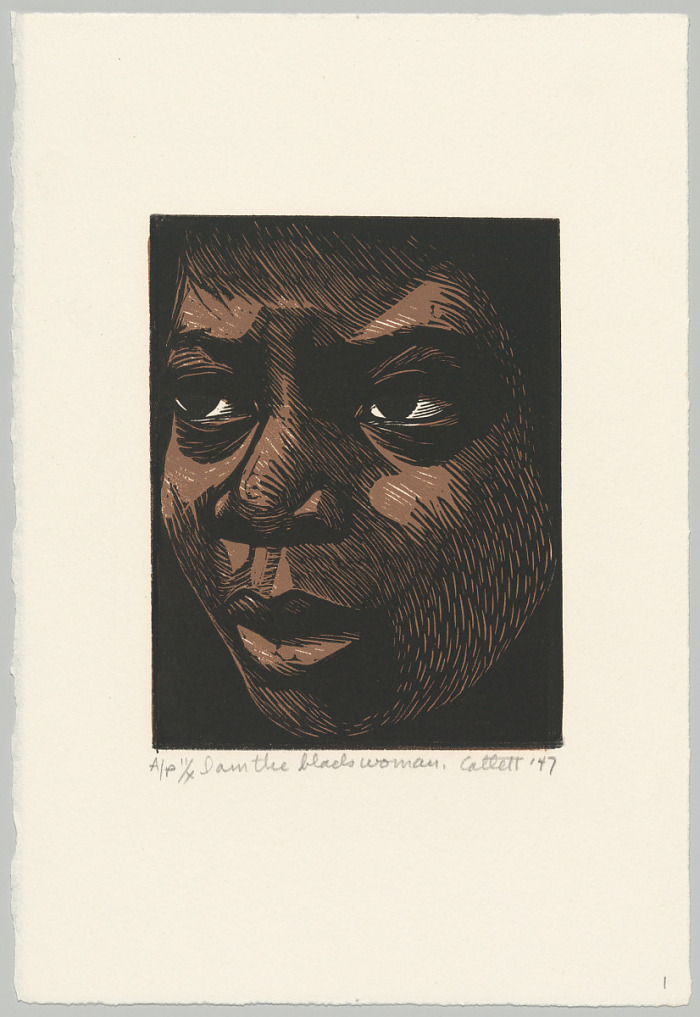

Latin American Women Modernists: Elizabeth Catlett, I Am A Black Woman, 1946-1947; printed 1989, Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History & Culture, Washington, DC, USA.

Elizabeth Catlett’s (1915-2012) maternal and paternal grandparents were born into slavery, a legacy that influenced her printmaking and sculpture centered on women of color. In the early 1940s she lived in Harlem, then the center of a Black Renaissance in art and culture. By 1946, she headed to Mexico as a guest artist at the country’s premier printmaking collective, Taller Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Arts Workshop). There she made prints that protested social and political oppression. Soon her bold graphic art, activism, and Communist associations attracted the attention of US government officials who declared her an “undesirable alien,” effectively barring her from returning to the country. She subsequently became a Mexican citizen and continued to create prints like I Am A Black Woman that gave form to her dual identity as a Black American and a Mexican.

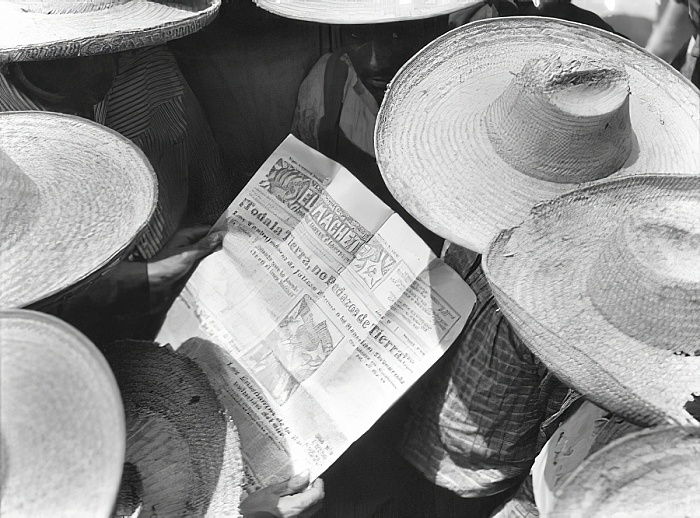

Latin American Women Modernists: Tina Modotti, Campesinos reading “El Machete”, 1929, Galeria Enrique Guerrero, Mexico City, Mexico. Artsy.

Tina Modotti (1896-1942) lived an adventurous and romantic life, moving from her native Italy to California, where she acted in silent movies. A meeting with the photographer Edward Weston led to her becoming his studio assistant, paramour, and traveling companion in Mexico. There she too took up the camera. She produced a body of photographs in which formally pristine compositions feature details like El Machete, the newspaper of the Communist Party, that hinted at her sympathy for the workers and dissatisfaction with the government. Eventually, her devotion to activism left little time for photography and resulted in her deportation from Mexico.

Latin American Women Modernists: Marion Greenwood, Industrialization of the Countryside, 1935–36, Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market, Mexico City, Mexico. Photograph by Bob Schalkwijk. Detail.

In 1934, two sisters from Brooklyn were among the ten artists assigned to paint the walls of an open-air market in Mexico City, the Abelardo L. Rodriguez Market. It was the height of the Mexican Mural Movement when Diego Rivera and his fellow artists painted scenes celebrating Mexican independence and identity in the wake of the country’s Revolution. Working in what was called a social realist style, Marion Greenwood (1909-1970) depicted The Industrialization of the Countryside, beginning with ancient canal construction and progressing to urban protests. Meanwhile Grace Greenwood’s (1905-1979) Mining rendered the capitalist exploitation of mineral resources. The press from Moscow to Washington, D.C. praised the market project. Furthermore, Rivera named the Greenwood sisters “the greatest living woman mural painters.”

Latin American Women Modernists: Leonora Carrington, The Lovers, 1987, private collection. WikiArt.

The British-born Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) studied art in London, where she met and became romantically involved with the artist Max Ernst. She moved with him first to Paris and then to the south of France. During this time, she painted pictures influenced by Surrealism, a movement in which Ernst and others attempted to express the workings of the subconscious via fantastic images and illogical pairings of objects. This led Carrington to include horses or hyenas in magical scenes. Soon after World War II broke out, Ernst was interned as an enemy alien in a Nazi prison camp. The emotionally distraught Carrington moved to Spain, then New York, and finally to Mexico. In its creative atmosphere, she produced her most personal pictures like The Lovers, where hooded monks and strange animals inhabit an imaginative nightscape.

Celeste Donovan, “Icons behind Altars: María Izquierdo’s Devotional Imagery and the Modern Mexican Catholic Woman,” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 26 (2010): 160-179.

Harper Montgomery, “Reproduction: Norah Borges Draws Modern Femininity,” The Mobility of Modernism: Art and Criticism in 1920s Latin America (Austin: U. Texas Press, 2017), pp. 152-189.

Hayden Herrera, Frida Kahlo. NY: Rizzoli, 1992.

James Oles, Hermanas Greenwood en México. México D.F.: Circulo de Arte, 2000.

Juan Antonio Molina, “Estrada Palma 261: Still Life with Dream about Amelia Peláez,” Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 22 (1996): 220-239.

Julia Codesido (1938-1979): Muestra Antológia. Lima, Peru: Centro Cultural, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Peru, 2004.

Leonora Carrington-The Mexican Years, 1943-1985. San Francisco: Mexican Museum, 1991.

Margaret Hooks, Tina Modotti. London: Phaidon, 2005.

Melanie Herzog, Elizabeth Catlett: in the image of the people. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2005.

Stephanie D’Alessandro and Luis Pérez-Oramas, Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil. Chicago, IL: Art Institute of Chicago, 2017.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!