A Feeling of Nostalgia: Art by Fu Wenjun

For centuries, China was one of the greatest and wealthiest civilizations, and perhaps it is now returning to its historical position. Artist Fu...

Roma Piotrowska 8 June 2019

22 December 2025 min Read

In a moment when museums around the world are rethinking their histories, collections, and social responsibilities, a dialogue held in Łódź, Poland, between Muzeum Sztuki and Lenbachhaus, offers a striking perspective on how modern art institutions were shaped not only by masterpieces, but by politics, generosity, exclusion, and resistance.

On October 30, 2025, at ms² in Łódź, Daniel Muzyczuk, Director of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, sat down with Stephanie Weber and Melanie Vietmeier from Munich’s Lenbachhaus to explore the shared yet conflicted legacies of two of Europe’s most important modern art museums. Their discussion—spanning avant-garde donations, wartime trauma, erased women artists, and the power embedded in museum buildings—reveals why the questions raised by Kandinsky and Strzemiński remain urgently contemporary.

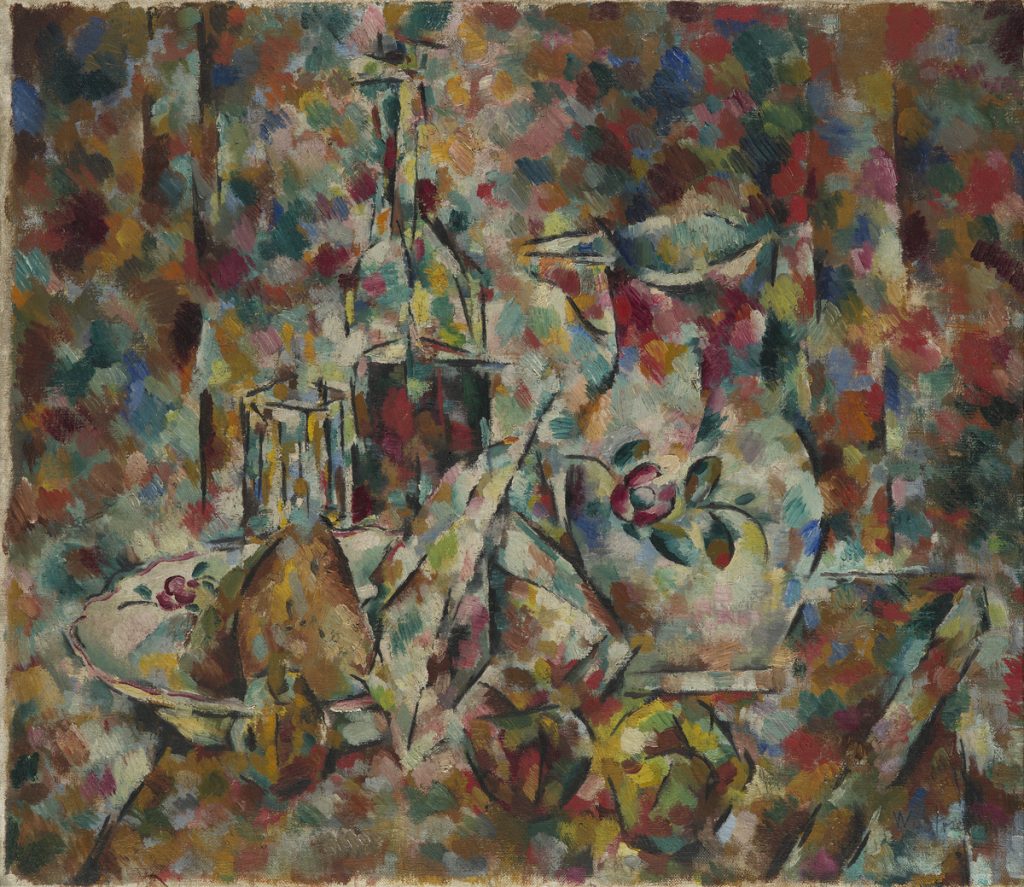

Władysław Strzemiński, Still Life VI, 1926, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Łódź, Poland.

Founded only two years apart—Lenbachhaus in 1929 and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in 1931—both museums emerged from the spirit of early 20th-century modernism, rooted in artistic experimentation and collective vision. Their formative collections were not built through market acquisitions but through acts of artistic generosity that transformed the institutions forever.

For Lenbachhaus, this turning point came in 1957, when Gabriele Münter, co-founder of Der Blaue Reiter, donated nearly 1,000 works to the museum, including key paintings by Wassily Kandinsky and herself. This single gesture reshaped the museum’s identity and positioned it as one of the world’s most important centers of modern art.

In Łódź, a similarly radical act defined the Muzeum Sztuki. The core of its collection was donated by the artists of the “a.r. group“—among them Władysław Strzemiński and Katarzyna Kobro—who believed that avant-garde art should belong to society, not private collectors. Their donation laid the foundation for one of the world’s earliest museums of modern art.

Yet both institutions also carry the scars of history. During World War II, Nazi authorities imposed new structures, ideologies, and personnel. Lenbachhaus was partially destroyed; the Herbst Palace in Łódź—today one of the Muzeum Sztuki’s branches—was completely demolished and later reconstructed. These material ruptures continue to shape how each museum understands its past and its responsibilities today.

Władysław Strzemiński, Urban Composition 12, 1932, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Łódź, Poland.

One of the most compelling threads of the dialogue focused on architecture as ideology. Lenbachhaus operates within the former villa of Franz von Lenbach, a successful 19th-century painter closely tied to elite patronage. Muzeum Sztuki’s ms² branch occupies a former industrial space, while another branch is located in a reconstructed palace once owned by powerful industrial families.

What does it mean for a museum to inhabit such spaces? How do class, labor, and economic histories shape the narratives museums tell—or silence? The speakers reflected on how buildings are never neutral containers for art but active participants in institutional memory, power relations, and social hierarchies.

ms² branch of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, Łódź, Poland. Photograph by HaWa. Courtesy of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

From architecture, the discussion moved toward broader questions of visibility and exclusion. Weber and Muzyczuk addressed the systematic erasure of women artists from art history, despite their central roles in shaping modernism. Münter’s long overshadowing by Kandinsky served as a powerful example of how gender bias distorts artistic canons.

The dialogue also touched on race, class, and structural inequality, asking how museums can critically engage with their own histories rather than merely celebrate them. Can categories such as “modern” and “contemporary” still serve us, or do they limit more than they explain? And how can museums avoid reproducing the very hierarchies they claim to challenge?

Meeting between staff members of the Museum Sztuki in Łódź and the Lenbachhaus, 2025. Courtesy of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

Rather than offering definitive answers, the speakers embraced complexity. The future collaboration between Muzeum Sztuki and Lenbachhaus, they suggested, will be built not only on shared avant-garde traditions but also on the conflicted, multilayered legacies both institutions have inherited.

At its core, the dialogue returned to a fundamental question: What is the purpose of a museum today? Is it a guardian of masterpieces, a site of critical reflection, or a space for social negotiation? Between Strzemiński and Kandinsky, between factory and villa, the answer remains deliberately open—inviting audiences to look again, and to look differently.

Text by Natalia Królikowska.

Project “Between Strzemiński and Kandinsky—Study Visits at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź and Lenbachhaus in Munich” is funded by the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage under the Kultura Inspirująca program, 2025–2026.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!