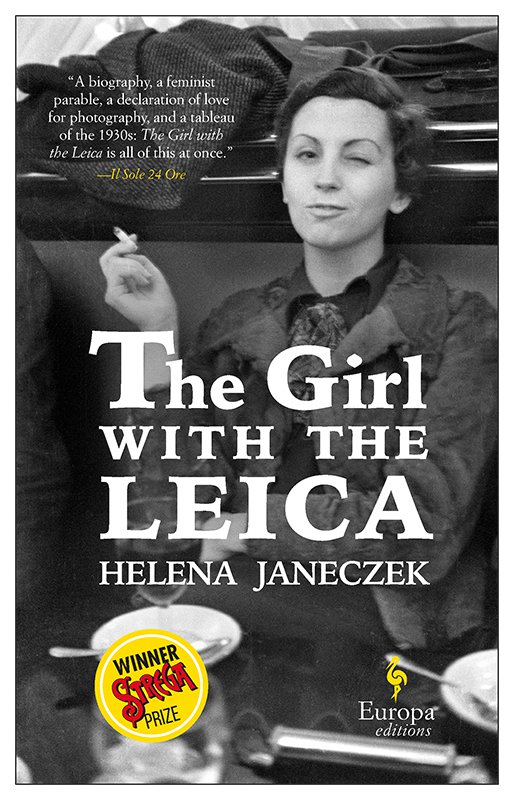

Have you ever heard of the photographer Gerda Taro? You may know her as Robert Capa‘s girlfriend and muse, and I’m sure you have heard of Capa at least once. Well, Helena Janeczek in her book The Girl with the Leica, winner of the Strega Prize of 2018, digs deep into Taro’s story showing it for what it really is: a modern feminist hero’s story.

Janeczek makes us see Gerda through the eyes of three people who shared part of their lives with her. The novel starts with a phone call between two men who both fell in love with Gerda in their youth, Willy Chardack and Georg Kuritzkes, years after Gerda’s death.

That call transports them back in time, to the Paris of the 1930’s, just before the rise of Nazism. It wasn’t an easy time, but back then Gerda represented a symbol of freedom, justice, and all the values that the Nazi regime was going to delete.

With the stories and thoughts of Willy, Georg, and Ruth Cerf (Gerda’s best friend), we get to know Taro and cannot help but be enchanted by her too.

From Gerta Pohorylle…

First we meet Gerta Pohorylle, a girl born in Stuttgart who comes from a bourgeois family of Polish-Jewish origin. Despite this, she takes an interest in the socialist and labor movements from an early age; in fact, in 1933, she joins the German Communist Party and at the age of 23 goes to prison for seventeen days on a charge of anti-Nazist propaganda and subversive activity.

When she gets out, she decides to flee to Paris; which, at that time, was still a democratic city, and a stronghold of freedom for artists and intellectuals.

Flickr, Ur Cameras

At first sight she might seem a shallow, pretty, bourgeois girl. However, she immediately shows everyone that she is an independent woman with strong ideals who is not afraid to fight for them, and can support and take care of herself. We can’t underestimate this aspect of her character. Certainly in the 30’s in Europe women were far from obtaining equal rights.

…to Gerda Taro

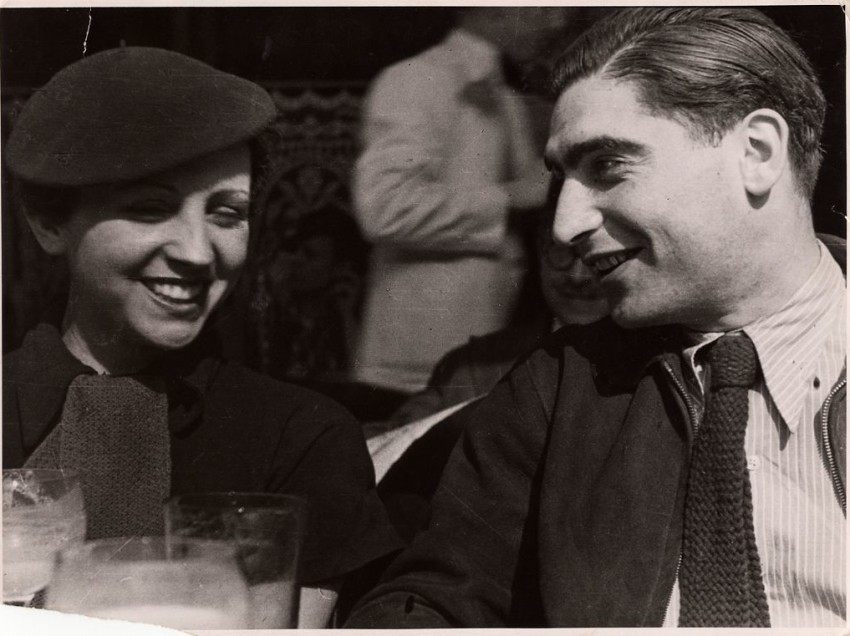

In Paris, Gerda meets a person whose life will change her forever: the Hungarian photographer Endre Ernő Friedmann. Their relationship starts as a friendship, even though she charms him right away (like she does with everyone else, after all).

However, she does fall in love with him day by day as he teaches her how to use a camera. He gives her first one as a gift; and, of course, it is a Leica.

Flickr, Ur Cameras

They do not just become lovers, but also work partners. It is Gerda who comes up with the idea of changing their names in order to break into the world of photography. This is pivotal since their names mark them as immigrants and Jews. They choose pseudonyms that could be more familiar overseas, and in fact, play on assonance with the names of the Italian-American director, Frank Capra, and the actress Greta Garbo.

From there, the brand Capa-Taro becomes more and more present in the most important French papers. Gerda had also understood that at that time she couldn’t become a famous photographer alone with a female name. Which is why she decided to associate with a man, as this could make her sell more photos. As a result many of Gerda Taro’s photos were credited to Robert Capa for decades.

(On Icp or Magnum‘s website you can see most of the photos taken by Gerda)

In art and literature it is very common that a work made by a female artist is then credited to a man. Just consider Judith Leyster, whose artworks were attributed to her male contemporaries; or the Canadian landscaper Caroline Louisa Daly, who was called Charles Daly for two hundred years; or even Joanne Rowling, better known as J. K. Rowling, whose publisher thought that a book written by a woman could be not as appealing for a male audience. And I could go on for hours!

The Spanish Civil War

In 1936, the Spanish Civil War broke out. This war was between the nationalists, led by Francisco Franco and aided by Hitler, Mussolini, and the Republicans led by the Popular Front. Most historians regard this conflict as a laboratory for the Second World War.

Many European countries like England and France decided to remain neutral; which is why many intellectuals, workers, artists- both men and women- decided to join the International Brigades to fight as volunteers.

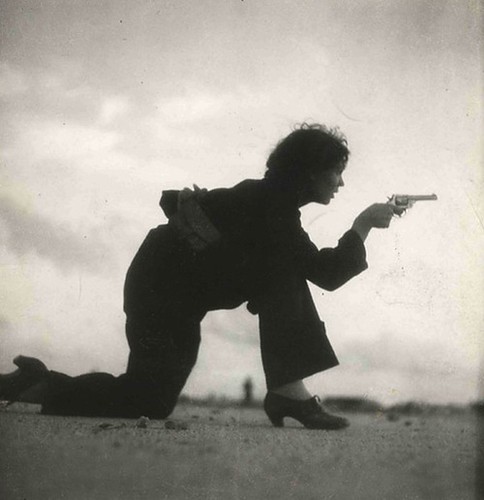

Taro and Capa couldn’t stand by and watch, so they jumped at the first chance they had to leave for Spain. The magazine, Vu, hired them as photo-reporters, but their pictures soon appeared on the most important papers and magazines, as well, including Life.

Gerda wanted to show the war from the point of view of the civilians and Popular Front’s militiamen. She wanted to make people understand that non-intervention was a crime that would lead to an unacceptable loss of freedom: the right of highest value for her.

In the book, Capa has a conversation with Gerda’s ex-boyfriend, Georg Kuritzkes, which helps us understand Gerda’s great dedication:

“At the end of the day, the only thing that Gerda loved unconditionally was not me, or you, or anyone else, but all those who spent their life fighting against fascism, it was Spain and her work beside the Spanish people.”

Helena Janeczek, The Girl with the Leica, 2017, p. 231

Her photographs represent the fighters’ pride, but also the desperation and death that war always brings, touching everyone’s lives; and certainly including her own.

An Untimely Death

“If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.”

Robert Capa

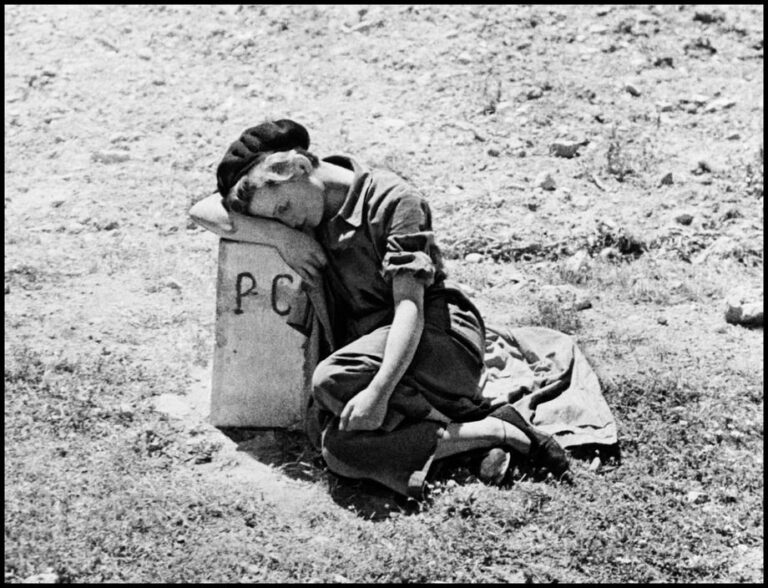

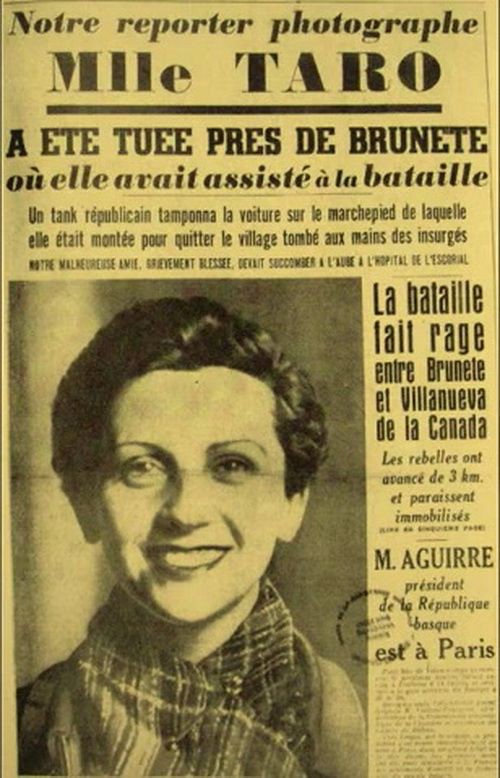

Gerda got too close. On the 25th of July 1937, during the Republican Army retreat at the Battle of Brunete, a tank ran over her. Even though they immediately transported her to Brunete Hospital, she died the following day.

Those who were present said that, before dying, she just wanted to know if her cameras and photos were safe. Gerda was only 26 when she died, but everyone will always remember her as the first female photographer to be on the front line and die during the war.

-

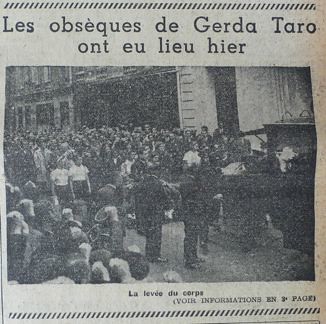

Gerda’s funeral procession on a French newspaper, 1937. Flickr, Ur Cameras -

The news of Gerda’s death on a French newspaper, 1937. Flickr, Ur Cameras

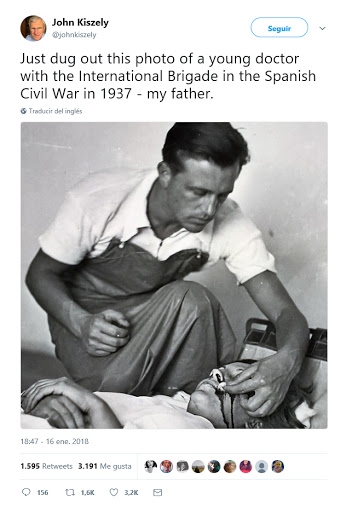

In 2018 the son of Janos Kiszely, the doctor who treated her, found the last heartbreaking photo of Gerda:

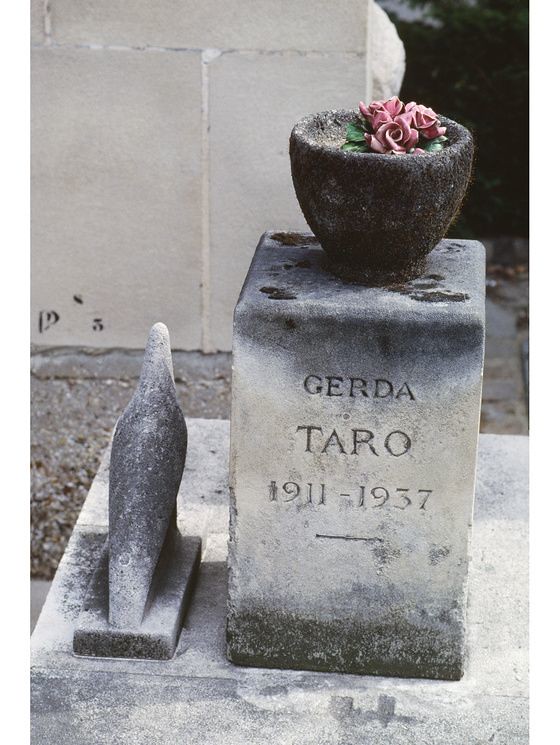

The 1st of August 1937, the day of her 27th birthday, tens of thousands of people turned out to the streets of Paris for her funeral procession. The poets Pablo Neruda and Louis Aragon read her eulogy, while the artist Alberto Giacometti created a monument for her grave at Père-Lachaise Cemetery using the Horus falcon, a mythical bird symbolizing light and resurrection.

Death in the Making

One year later, Capa, still devastated by his loved one’s death, published Death in the Making, a photographic book that documents the Spanish Civil War with Capa-Taro photographs, which is dedicated to his professional and life partner. The dedicatory reads:

“For Gerda Taro, who spent one year at the Spanish front – and who stayed on.”

Death in the Making, dedicatory, 1938, Robert Capa.

It will take a long time for Capa to recover from the shock of his partner dying, and he will always feel guilty for not being there for her in that moment. Since he had gone in Paris for ten days while Gerda was working on the battlefield, he was not present at the time of her death.

He will always say that Gerda was the woman of his life, calling her “my wife”, even if she had never accepted a proposal to marry him. She always preferred a relationship that could let her be free; one in which they were equals.

Capa used to say that the morning of the 26th of July 1937 was the day of his death too. Actually, his death was very similar to that of Gerda’s: it was in 1954 while reporting the First Indochina War.

The story of these two lovers who died for freedom and photography inspired many, including the British band Alt-J, who wrote the song “Taro” in 2012.

All of this, Gerda, still heartens us

Despite your death and your remains,

the ancient gold of your hair,

the fresh flower of your smile in the wind

and the grace when you jumped,

laughing at the bullets,

to fix battle scenes,

all of this, Gerda, still heartens us.

Poem of Luis Pérez Infante dedicated to Gerda Taro

Even if Gerda died unjustly and too soon, The Girl with the Leica is not about death, as demonstrated by the poem by Luis Peréz Infante at the beginning of the book. What people will always remember about Gerda is her ambition and her ability to remember the happy things of life, despite the horror she was witnessing.

But most importantly, what Janeczek makes us understand with this book is that Gerda was a fundamental element and the living embodiment of the change that was gaining ground in those years. On one side we see the anti-authoritarian current brought by the International Brigades, and on the other, the women’s empowerment she represented.

I hope I have convinced you that Gerda Taro was not only the girlfriend of a famous photographer, but a woman who had the courage to express herself as an artist and to sacrifice her life by reporting atrocities that she wanted to never happen again. And I hope that you will remember her name.

Here are many other striking stories of women artists!