Joséphine de Beauharnais: Patron of the Arts

Joséphine de Beauharnais was born in Martinique as Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie. She evolved into the sophisticated and cultured...

Maya M. Tola 20 May 2024

Fernando Botero once called himself “the most Colombian of Colombian artists,” as the majority of his works explore traditional themes from his home country and, in effect, serve as a guide through Colombian history and culture.

New York City, Barcelona, Bilbao, Madrid, Paris, Goslar, and Bamberg, Vaduz, Lichtenstein, Jerusalem, and Singapore, Yerevan. These are only some of the cities where Fernando Botero’s easily recognizable balloon-like sculptures can be found decorating parks, plazas, and other public spaces. Like his sculptures, Botero’s paintings reveal the artist’s fascination with volume and proportion by exaggerating the round, fleshy qualities of their models. Although sometimes labeled primitivism or naive art for its apparent technical simplicity, the originality and consistency of his style have led many critics to describe it simply as boterismo.

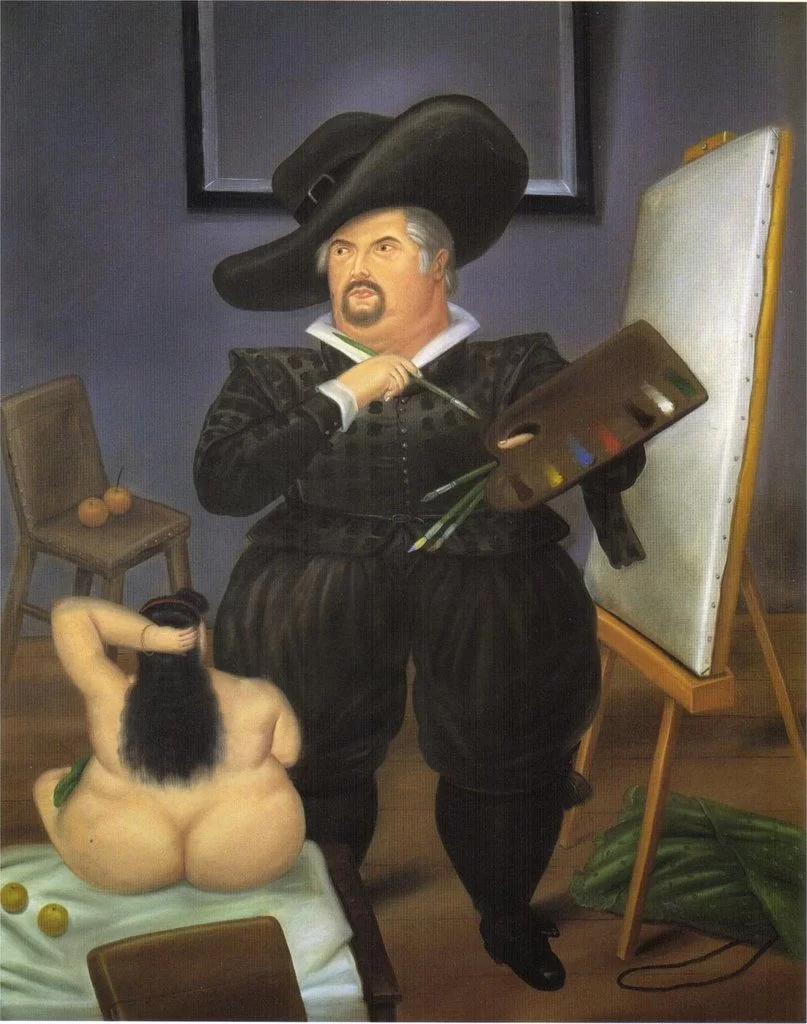

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, Self-Portrait as Velázquez, 1986, private collection. WikiArt.

Born on April 19, 1932, Fernando Botero developed a passion for art at an early age, and his first works were exhibited when he was only 16 years old. Inspired by the Spanish masters Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, the young Botero moved first to Barcelona and later to Madrid, where he studied at the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. In his Self-Portrait as Velázquez, the artist payed homage to his classical influences while further innovating his own unique style.

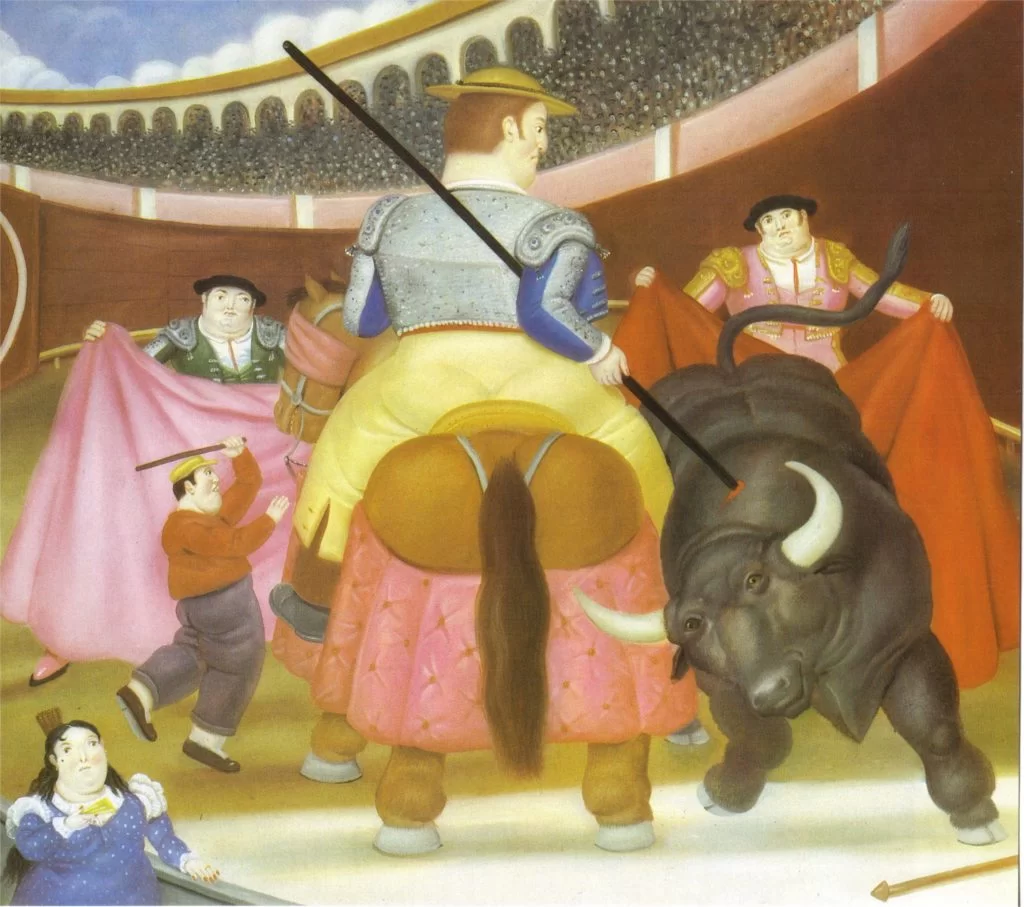

Although most commonly associated with southern Spain, the sport of bullfighting has been practiced in Latin America since colonial times. In fact, the plaza de toros of Mexico City is the world’s largest bullring, with the capacity to seat over 41,000 spectators. Historically, Colombia has been no exception, but recent protests from animal rights groups have put pressure on the government to ban not only bullfighting but also cockfights and rodeo games in the country. Controversial as it might be, Botero himself spent two years of his youth training to become a torero, or bullfighter, before discovering his artistic talents.

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, The Pica, 1984, private collection. WikiArt.

In The Pica, he depicts the first stage of a bullfight in which two picadores enter the arena on horseback. Their job is to weaken the bull by stabbing the back of its muscular neck with special lances called varas. The two picadores are followed in turn by three banderilleros, who further weaken the bull by stabbing its shoulders with pairs of barbed sticks designed to make the animal bleed. In the third and final stage, the bullfighter enters the ring with a sword and cape, known as a muleta, to finish the task. Only the bullfighters who are able to skillfully kill a full-grown animal in one attempt by piercing its heart through the shoulder blades can earn the title of matador de toros.

Botero once said that,

man needs music, literature, and painting – all those oases of perfection that make up art – to compensate for the rudeness and materialism of life.

Quoted in Manhattan Arts.

While Colombia has many traditional styles of music and dance, cumbia is the one that has achieved the most international popularity. Originally, cumbia evolved as a mixture of Indigenous, black, and Spanish musical traditions in Colombia’s coastal region but has since spread not only throughout the entire country but also to most of Latin America.

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, Dance in Colombia, 1980, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

In his painting Dance in Colombia, Botero depicted a couple moving energetically to the rhythm of the country’s lively music. Despite presenting both the couple and the band as well-dressed for a night out, Botero subtly revealed the working-class origins of cumbia by portraying the bar as one completely littered with fruits and cigarettes.

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, The Poet, 1987, private collection. WikiArt.

In the world of literature, Colombia is perhaps most commonly associated with the works of Gabriel García Márquez, who was awarded the Nobel Prize after the publication of his masterpiece Cien años de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) and was at the forefront of the Latin American literary boom of the 1960s and 1970s.

The Poet is Botero’s representation of a writer, reclined beneath a grove of fruit trees, pencil, and paper at hand, searching for inspiration. Perhaps it was just in such a setting that García Márquez composed some of his most famous cuentos, or short stories, which would serve as the foundation for realismo mágico, a modernist literary genre native to the Latin American canon that blends fantastical elements with natural and familiar scenarios.

Upon gaining its independence from the Spanish Empire in 1819, Gran Colombia consisted of what are the present-day countries of Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama as well as parts of Peru, Guyana, and Brazil. Although considerably smaller today, Colombia has retained much of its geographic diversity, with coasts on both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans as well as a stretch of the Andes Mountains that separates the coastal region from the Amazon Rainforest and grassland plains on the inland side of the country.

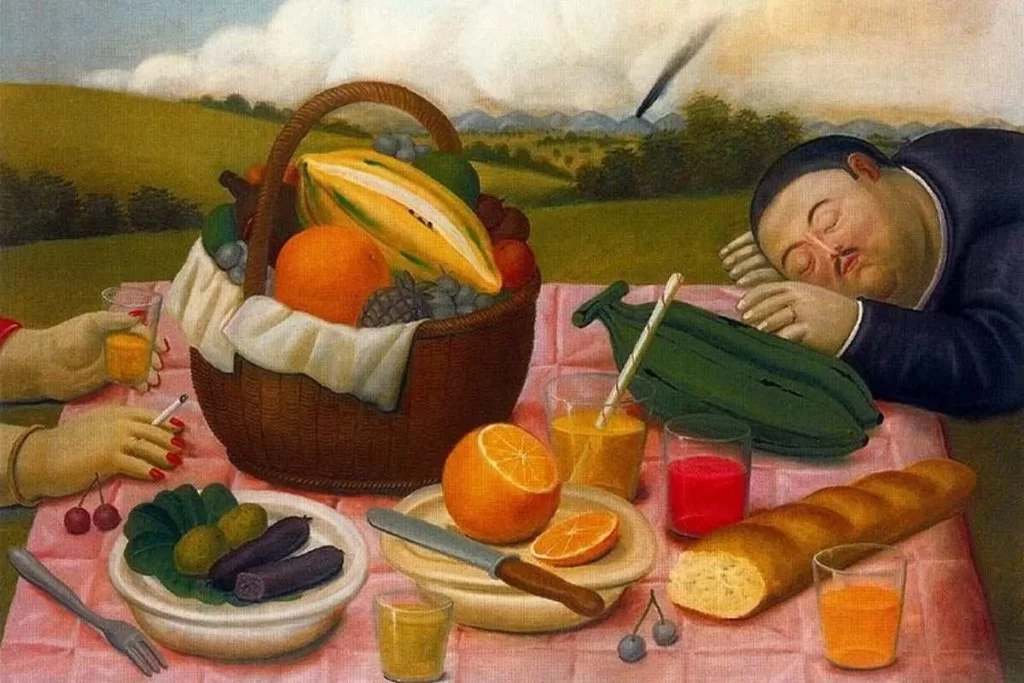

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, Picnic, 1989, private collection. Museum Pass.

These grasslands are the setting for Botero’s Picnic, which portrays a couple relaxing after a feast of grapes, oranges, and an assortment of exotic tropical fruits. As the picnickers enjoy their leisure time, one of the Andean region’s many active volcanoes erupts in the background. Botero himself, however, was from a city. While significantly smaller than Bogotá, the modern metropolitan capital of 10 million inhabitants, the artist’s hometown of Medellín is experiencing a renaissance as a contemporary cultural center and growing tourist destination.

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, The Street, 1995, private collection. Christie’s.

Although originally inspired by Medellín, The Street could be a representation of many towns in Latin America. With its narrow cobblestone paths and historic buildings, the dreaminess of the setting is contrasted with what appears to be a busy midday scene, as families, priests, and businessmen all greet each other before continuing hurriedly on their separate ways.

Despite its rich cultural heritage, its beautiful landscapes, and its historic cities, Colombia has long had a stigma for violence and instability. Since 1964, left-wing guerrilla groups such as the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) and the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) have lead an insurgency against the Colombian government. However, as the government has failed to control the rebel groups, a number of right-wing paramilitary organizations have formed in an attempt to counter the guerrillas themselves. Over the decades, both sides have been accused of involvement in the country’s drug trade, allying themselves with crime syndicates such as the Cali Cartel or Pablo Escobar’s infamous Medellín Cartel.

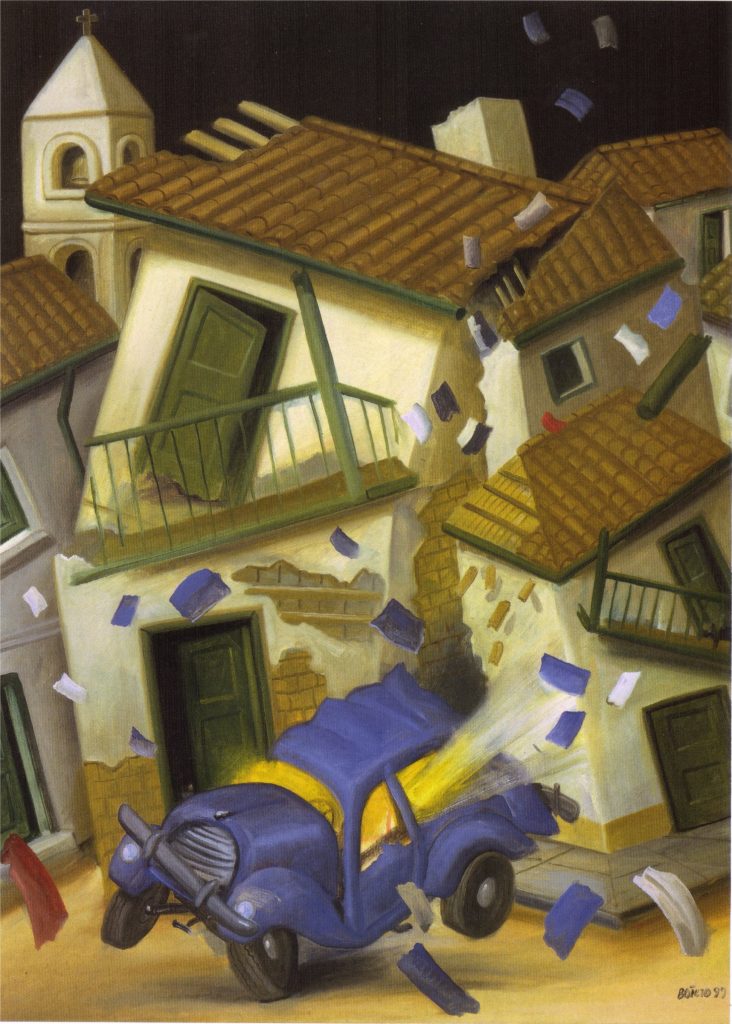

Colombian history: Fernando Botero, Car Bomb, 1999. Arthive.

Car Bomb is Botero’s depiction of the violence that has now affected the country for over half a century, making it the longest ongoing conflict in the Western Hemisphere and leaving Colombia with the world’s second-highest number of internally displaced persons after Syria. Under a recent peace treaty, FARC rebels have agreed to disarm and hand over their weapons to the United Nations, but other groups still remain active. Today, “the most Colombian of Colombian artists” resides in Monaco.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!