Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

25 September 2023 min Read

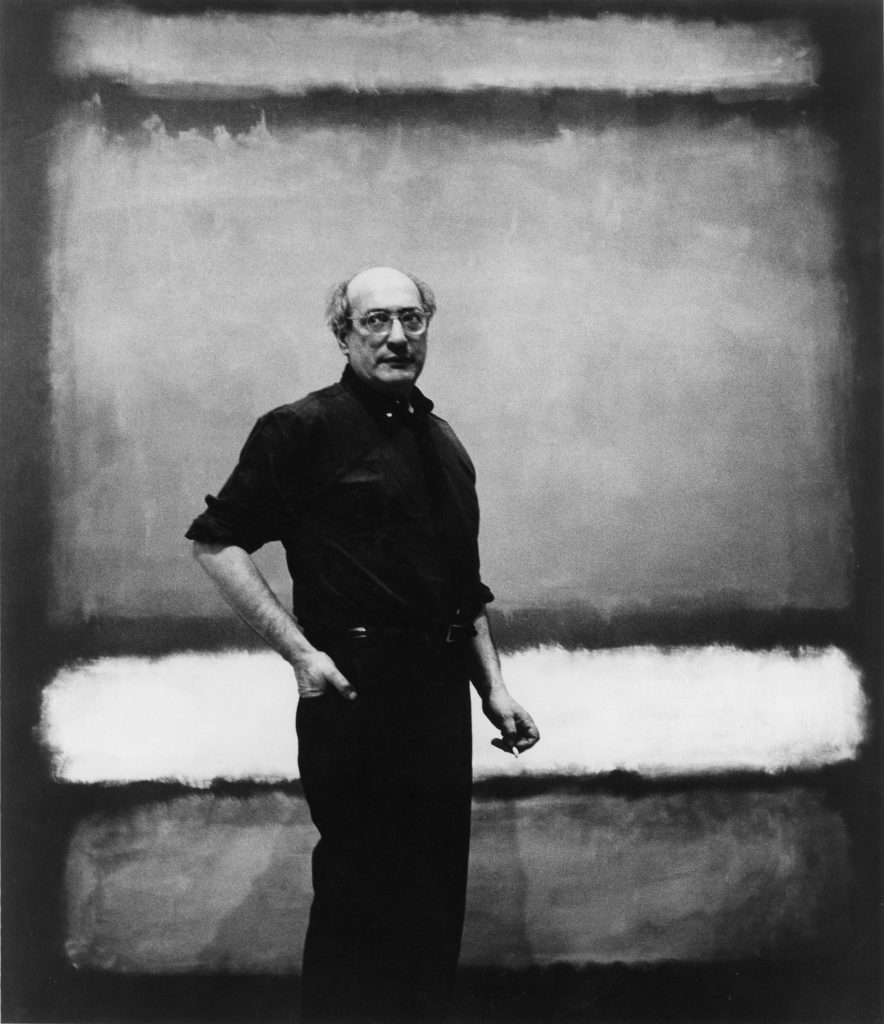

There is no doubt that when we think of Mark Rothko (1903 – 1970), we picture his large, abstract canvases with representations of human feelings and drama. He painted them from 1950 to 1970 and they made him the artist we know him as today. But before becoming an Abstract Expressionist legend, Rothko was looking for his place in the art world. Here we will introduce you to Rothko’s early artworks.

Rothko’s surprising and unexpected early works differ much from what we usually associate with the American artist. Despite everything, when we look at them it’s evident how the artist, through all of his life, was an ardent worshipper of depictions of human feelings and how intensively he was looking for them in art – not only in his own art but also in the art of the Old Masters.

The real essence of the great portraiture of all time is the artist’s eternal interest in the human figure, character and emotions – in short, in the human drama. That Rembrandt expressed it by posing a sitter is irrelevant. We do not know the sitter but we are intensely aware of the drama.

Rothko on the exhibition The Art of Rembrandt (1942, Metropolitan Museum New York).

In 1923, the artist gave up his studies at Yale University and moved to New York City. There he spent hours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and attended classes at the Art Students League, briefly studying under American Cubist, Max Weber. In the late 1920s, he met the modernist painter Milton Avery, whose simplified and colorful depictions of domestic subjects had a profound influence on Rothko’s early development. At this time, Rothko was particularly interested in Rembrandt’s work – his Self-portrait from the National Gallery of Art in Washington especially caught his eye and echoed in his self-portrait from 1936.

Rembrandt wasn’t the only Old Master admired by the artist. Rothko first saw the original of Vermeer’s The Art of Painting in the 1950s. He worked on the basis of a reproduction citing the blue dress and the window by which the young woman stands. He altered the style, context, and pose, and simply modernized the subject. The artist’s Mary holds her hand as though pregnant. The curtain, all the decorations, as well as the painter and his easel, vanish, however. The space and the protagonist appear flat and abstract.

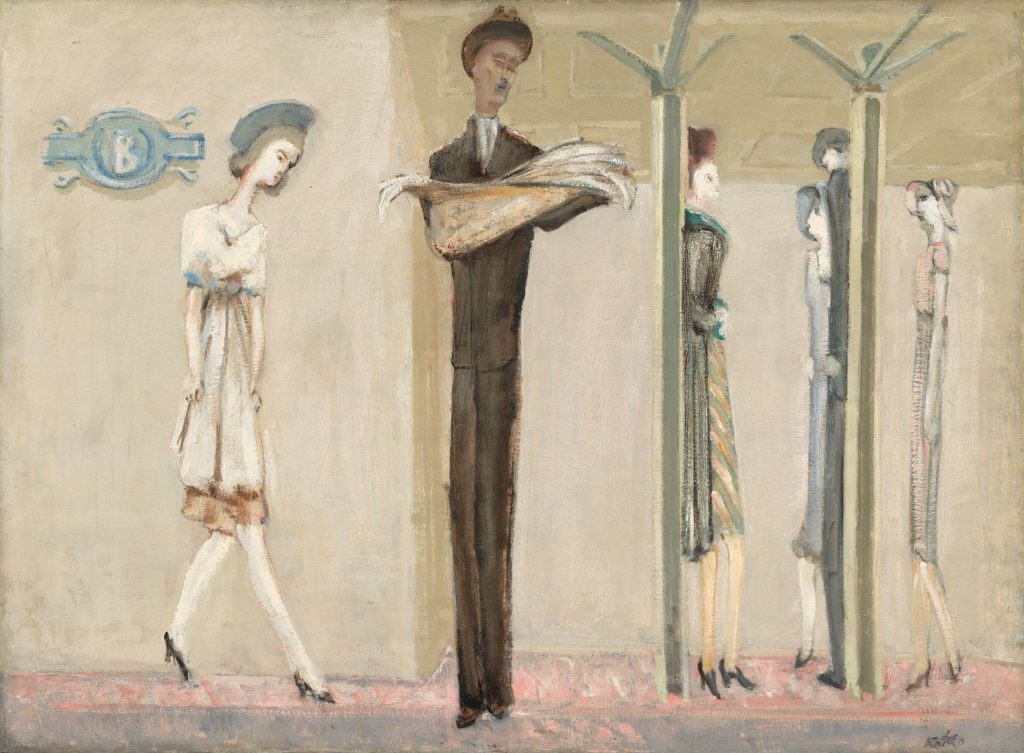

In 1929, the artist began teaching children at the Center Academy of the Brooklyn Jewish Center, a position he retained for more than 20 years. Then Rothko painted mostly street scenes and interiors with figures. In his subway scenes, faceless passengers stand isolated on the platform or descend the stairs against bold, empty backgrounds.

In the 1940s, perhaps because of what was happening in the world, the artist shifted from scenes of real life to symbols and myths. The artist felt that if art were to express the tragedy that pushed civilization to the edge, a new idiom had to be found. “It was with the utmost reluctance that I found the figure could not serve my purposes … But a time came when none of us could use the figure without mutilating it,” he said.

The most crucial philosophical influence on Rothko in this period was Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Nietzsche claimed that Greek tragedy served to redeem man from the terrors of mortal life. The exploration of novel topics in modern art ceased to be Rothko’s goal. From this time on, his art had the goal of relieving modern man’s spiritual emptiness. He believed that this emptiness resulted partly from the lack of a mythology.

The artist’s pieces from 1946 to 1949 have been named by art critics as “multiform” paintings. Rothko never used the term multiform himself, yet it is an accurate description of these paintings. The artist himself described these paintings as possessing a more organic structure and as self-contained units of human expression. The blurred blocks of various colors contained a “breath of life” he found lacking in most figurative paintings of the era. Writing in 1947, he described his paintings as “dramas”, but added that the use by contemporary artists of figurative subject matter to convey emotions and experiences was no longer practicable: “With us, the disguise must be complete”, he asserted. The “multiforms” brought the painter to a realization of his mature, signature style, the only style the artist would never fully abandon. The fields of color were about to arrive.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!