As the third piece in our series, I present my favorite paintings from the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (MnBA) of Rio de Janeiro. There are works by Brazilian as well as European masters. The most interesting to me were the works that represent Brazil’s environment (such as the jungle and exotic fruits), people, historical events and typical scenes of life. So it comes as no surprise that my favourite paintings are all made by Brazilian artists.

Djanira da Motta e Silva: Caboclinhos, 1952

Djanira (Brazil, 1914 – 1979) – she’s often referred to by her first name – was a female painter who excelled in the naïve art genre in Brazil. Fellow artists consider her artistic work very important in showcasing Brazilian popular culture. Her paintings can be grouped into three main topics: religion, Brazilian landscapes, and common scenes of Brazil. This painting in Belas Artes of Rio falls into this latter category. Caboclinhos depicts a festival scene with a group of musicians playing among coconut trees. Caboclinhos is a traditional dance that is performed during carnival in Pernambuco in the northeast of Brazil. Djanira’s musicians play the typical instruments for caboclinhos: a flute and a Brazilian bass drum. The musicians wear shirts, linen trousers and a handkerchief – typical on the fields in hot weather. Likewise, the black character represents Brazilian society.

Read about Candomblé, a traditional celebration in Brazil of African origins.

Djanira’s most powerful tools in her painting are her bold colours and the absence of perspective. Both of these tools result in a childlike work that gives the impression that the artist paints without any formal education, just from her heart. In fact, she mostly learned to paint by herself. Her inspiration came from her childhood. She grew up in the town of Avaré (a town in São Paolo state, basically a big ranch), where she saw the farmers’ simple and laborious life. Her contemporaries stigmatized her art as “primitive” and thus they marginalized her within Brazilian modernism. However, being an outsider gave her independence from the academic schools, allowing her to elaborate her own imagery of social topics.

Pedro Peres: Elevation of the Cross in Porto Seguro, 1879

This work depicts a very important moment in the history of Brazil, which has been painted by many artists: the erection of the cross in Porto Seguro. Porto Seguro in Bahia State was the place on the Brazilian shore where the Portuguese landed with their conquering ships in 1500. The picture builds on the contrast of the cross in the centre and the “savages” who surround it. Portuguese colonists erected the cross in their typical clothing, which symbolises Christianity and the European values of the time.

In the surroundings we see the Brazilian jungle, with lush trees and naked, tribal-looking people. That period’s elitist viewpoint considered the indigenous as savage groups. So this is the way Peres depicted them: without clothes, almost barbarian. He created the picture following the European narrative and the rules of European academic painting. In the colonies at that time, this wasn’t unusual!

When looking at this picture, the viewer is bound to recall another important and often painted moment of Brazilian history: the first mass directed at indigenous people. Jesuit missionaries, who arrived in Brazil together with the colonists, carried out the mass. Their mission was to convert the indigenous to the Catholic religion. Victor Meirelles, another famous artist and teacher of Peres, painted a very famous interpretation. At the end of the 19th century, when Peres made this painting, it was popular to depict historical moments on paintings. Consequently, these artists – like Peres (Portugal 1841 – Brazil 1923) – created a Brazilian universe from a European point of view.

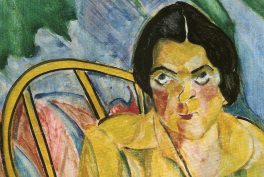

Emiliano Di Cavalcanti: Settlers, 1944

Di Cavalcanti (Brazil, 1897 – 1976) worked on freeing Brazilian art from European influences. He developed this idea during his trip to Europe. Instead, he wanted to embrace modernism by creating national art. This mission is actually not that easy! Despite painting about the Brazilian reality, the main source of inspiration for Brazilian painters were European artists – Picasso most of all. Di Cavalcanti still didn’t manage to completely remove all European influences. Unsurprisingly, among the main topics of his works we find mostly Brazilian subjects: mulatto women (children from white and indigenous parents), carnivals, black people, tropical landscapes.

Settlers depicts the scene of a black and a mulatto woman picnicking on a deserted landscape. In front of them are some of the typical fruits of the region: papaya, mangos, figs. The women are barefoot, wearing simple clothes, resting and daydreaming. Di Cavalcanti was charmed by women, so female characters are often the topic of his paintings. While in other paintings his women are elegant, here their clothing and their huge naked feet rather represent the peasant class and the closeness of earth. These motifs are central to Brazilian popular culture.

The silent, daydreaming facial expression of the characters lends the painting a bit of a melancholy feeling. Likewise the mainly monochromatic brown shade of the whole painting. He often added an element of misery to his paintings of working class people. Besides, he expressed his political views in his art in a subtle way. He was a very active communist and even went to jail twice because of it.

Antônio Parreiras: Gragoatá After the Storm, Niteroi RJ, 1886

I find it fascinating to look at old pictures of existing towns and landscapes and to compare them with their current look. That’s why I really like this picture! This painting depicts a district of the Brazilian Niteroi city (Rio de Janeiro State) called Gragoatá, which is essentially part of Rio de Janeiro today. Niteroi was an important shipping town at the end of the 19th century. Over the course of a century, this small place grew into a bustling business district of the rich – the other side of Rio de Janeiro. Many artists of the fin de siècle found inspiration in Niteroi.

Check out our budget-friendly practical guide to Rio de Janeiro and read about the best neighborhoods to visit.

Thus, there are plenty of paintings where art lovers can locate the exact view or vantage point. This painting portrays Praia Grande beach, which Parreiras (Brazil, 1860 – 1937) painted outdoors. The palm trees are typical of the Brazilian beaches. Similarly, among the hills in the background we recognize the famous Pão de Açúcar (Sugarloaf Mountain), the symbol of Rio. Despite Praia Grande being a significant harbour at that time, the painting rather catches an atmosphere of abandonment and underdevelopment.

On the picture we see a shipwreck and restless sailors who have just survived the storm at sea. However, these figures are not the protagonists of the scene, rather they are just part of the landscape. Hence, the painter uses the same colors for them as for the surroundings. Parreiras studied academic landscape painting at the Academia de Belas Artes in Rio. Interestingly, it was in the same building that houses the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes now. No surprise then that his paintings are in accordance with the European academic landscape painting style. In fact, he didn’t only go to Niteroi to paint, but it was his home town too. A few years after creating this painting he founded his outdoor painting school there.

José Correia de Lima: Portrait of the Heroic Sailor Simão, Coalman of the Steamboat Pernambucana, 1853

This portrait by José Correia de Lima (Brazil, 1814 – 1857) is an exception in the 19th century. Although at that time Brazilian portrait painting was exclusively reserved to the elite of the society, Correia de Lima chose a sailor, and above all, a black man as the subject of his painting. Nevertheless, black figures did appear on images, but only in the context of work (mostly slaves). Simão, the sailor on the picture, was a real person: a free man from Cape Verde, who saved a boat load of people in a shipwreck near the shore of Brazil. With this heroic act he became famous in the country. Newspapers wrote about him and poets dedicated writings to him.

In the painting, Simão’s shirt is half open, allowing a glimpse of his muscular body. Depicting black men with a focus on bodily features was typical at that time. Simão’s look is rather sad. He is holding a rope, which symbolises sailor men. The dark background is very simple, fitting to the social class of the sitter. Correia de Lima’s other paintings were of nobles. In those he created more detailed backgrounds: curtains, the inside of a room, a landscape through the window. José Correia de Lima was an academic painter with a tragically short life. I can’t help but imagine how many great portraits of the working class have never been created with this loss.

Antônio Henrique Amaral: Sequence One, 1971

Amaral (Brazil, 1935 – 2015) was a painter famous for his “banana” paintings, one of which I will introduce. While other painters also used bananas as subject, Amaral is the artist who made this fruit famous. His work is an important example of tropicália. This movement set the goal to create something uniquely Brazilian while taking influences internationally. It existed in music as well and included such well-known artists as Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil who fused Brazilian popular tunes with pop-rock.

Amaral was interested in politics, and after the rise of the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964), politics heavily influenced his work. He produced two series of banana paintings: he called the first one Brasiliana depicting healthy bananas. The second series was called Campo de batalha (“Battlefield”), where the paintings feature mutilated, rotting bananas. These fruits were hung, bound or violated by forks, knives and other metal weapons. The banana paintings bring across a political message: the rejection of the dictatorship in Brazil. Using violent images as a protest against the dictatorship connects him with his contemporary Brazilian artist, Antônio Dias, one of whose paintings I presented in my post about MALBA museum.

Sequence One belongs to the second series: it shows a branch of green bananas which are tied up with a rope. The green (and a bit of yellow) are the colours of the Brazilian flag, while the rope around the bananas reveals the terrible situation in the country at that time. Amaral boldly uses a close-up and cartoonish style with bright, simple colours in most of his works which are reminiscent of vibrant pop art and Andy Warhol.

Address: Avenida Rio Branco, 199 – Centro (Cinelândia) Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

Entrance: 8 BRL. Free on Sundays