Masterpiece Story: The Pineapple Picture

Known as the “pineapple picture,” this enigmatic 17th-century painting captures the royal reception of King Charles II. The British royal...

Maya M. Tola 3 September 2024

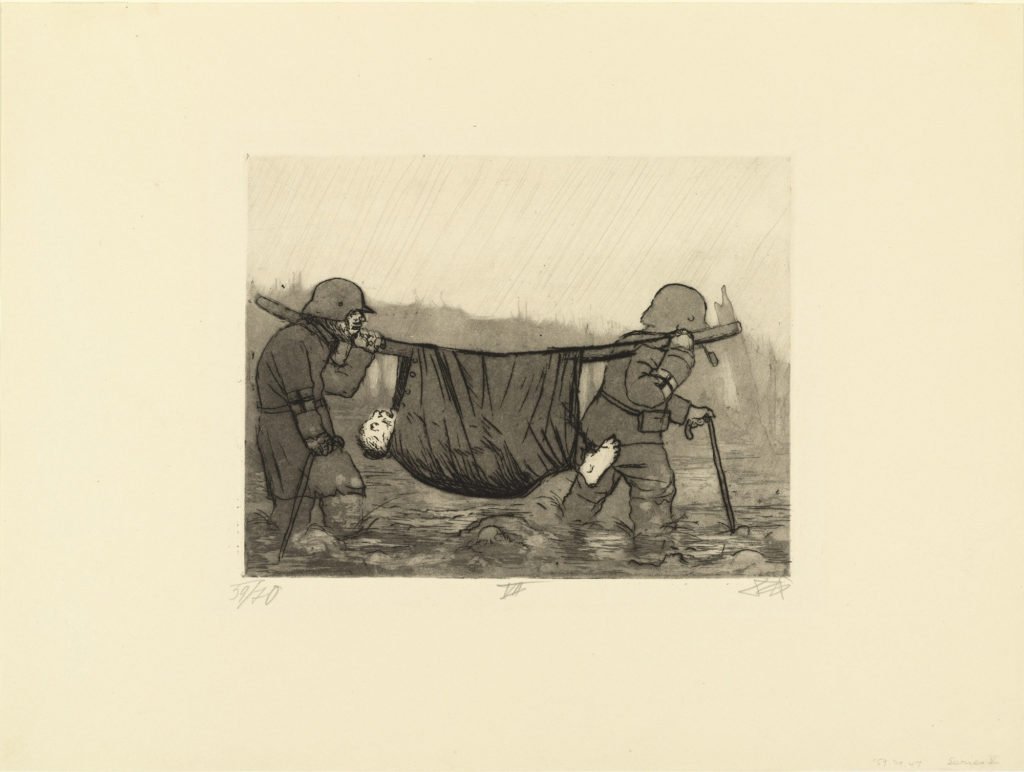

When the First World War, also known as the Great War, broke out, everyone was thrilled. The soldiers went happily to fight for their countries. All sides thought they would be winners and were arrogant towards their opponents. Many artists went to the battle, some even voluntarily. One of them was Otto Dix. However, the horror and the wretchedness of the trench warfare soon erased all hope for a quick victory.

Otto Dix is a very interesting figure in the art world of the 20th century. He survived the First World War and saw his works censored by the Nazis. Dix was a member of the New Objectivity movement (Neue Sachlichkeit). It evolved during the interwar era in Germany as an opposition to the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter). After the Great War, the Blue Rider took a non-figural direction due to the German defeat. The artists of the New Objectivity, including Max Beckmann and Georg Grosz, wanted to draw attention to the horrible reality of the new German society without idealizing it at all; a reality perfectly depicted in the etchings of Otto Dix.

According to Giulio Carlo Argan, a distinguished art historian, Otto Dix was to painting what Erich Maria Remarque (the author of All Silent From the Western Front) was to literature: the precise, merciless, almost photographic narrator of the horrors of the war and its obvious stupidity.

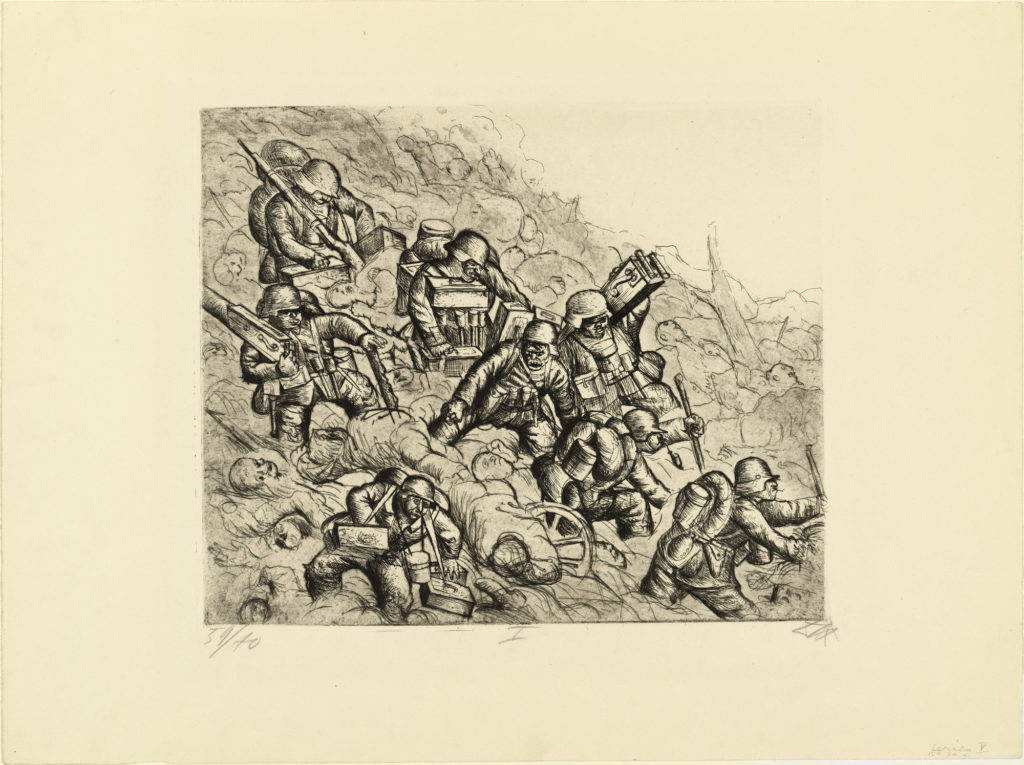

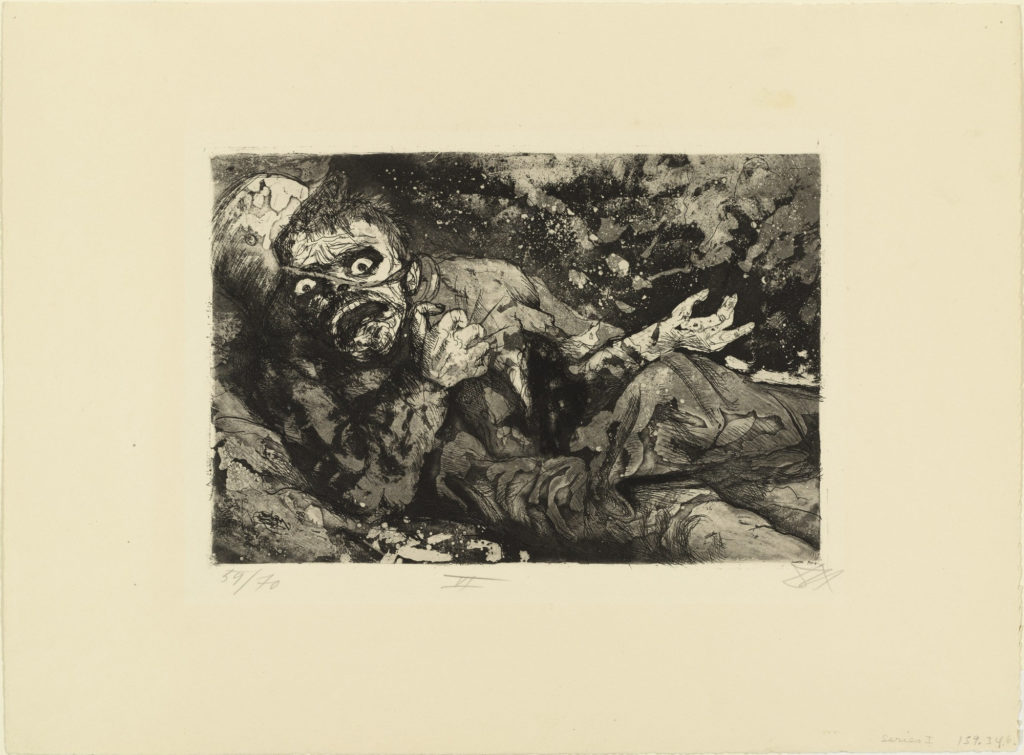

As aforementioned, Dix joined the war voluntarily. In order to kill time and to avoid the tediousness of the trenches, he started drawing. He used mostly coal and ink on postcards and drew what was in front of him; death, rot, bombs, mice, mud, and void. He sent around 300 drawings to a girl in Dresden, with whom he was friends. His family received another bunch.

The sketches were intended to be a visual testimony of the war without communicating an anti-war position. They profile the place and time without showing if any political side was either right or wrong.

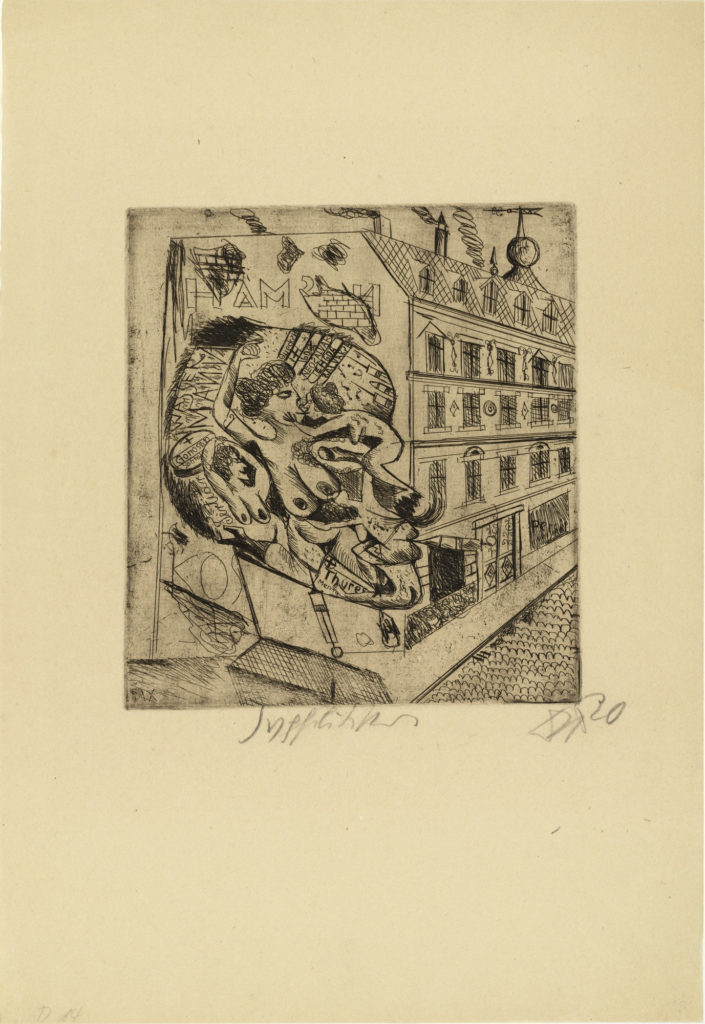

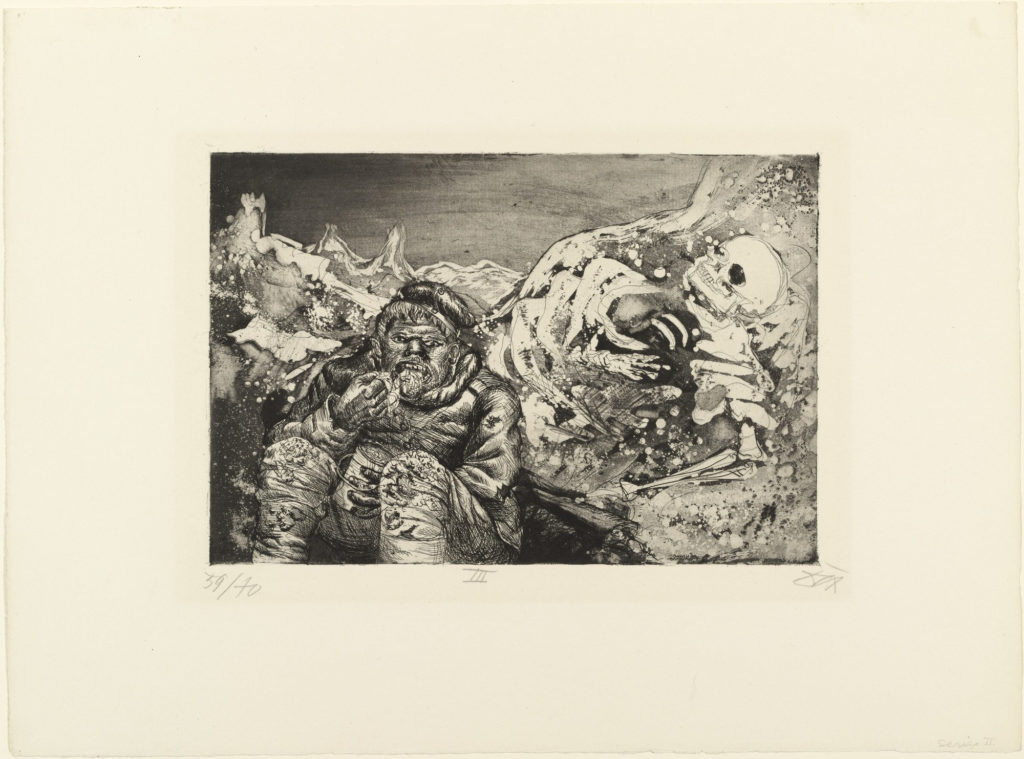

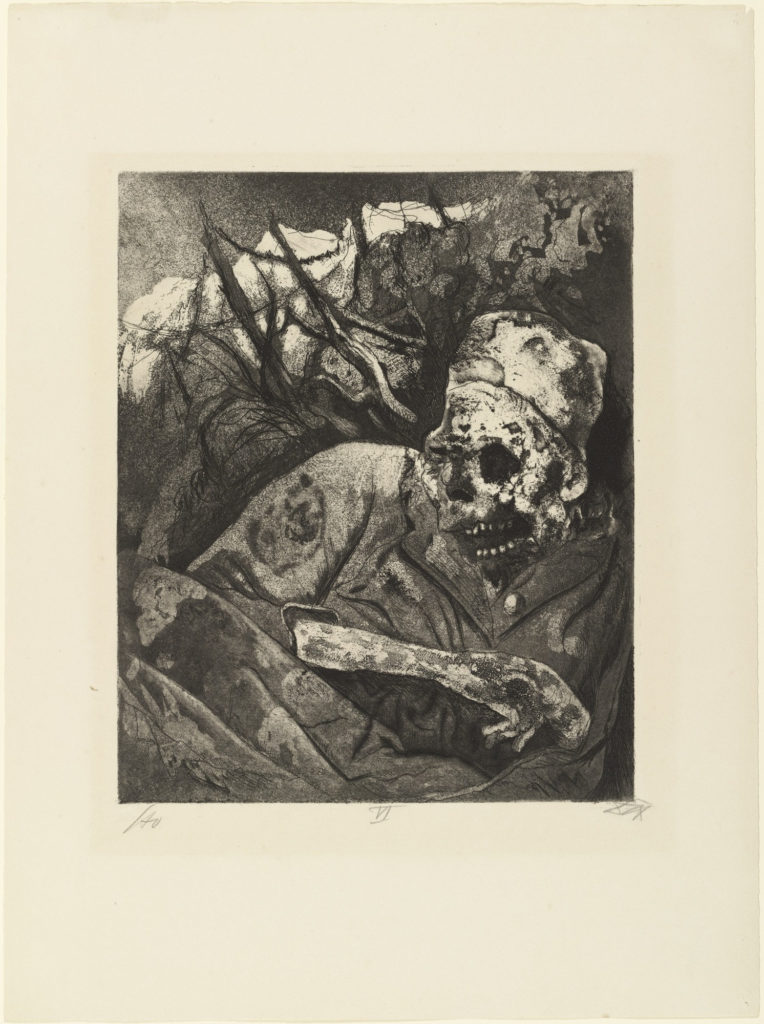

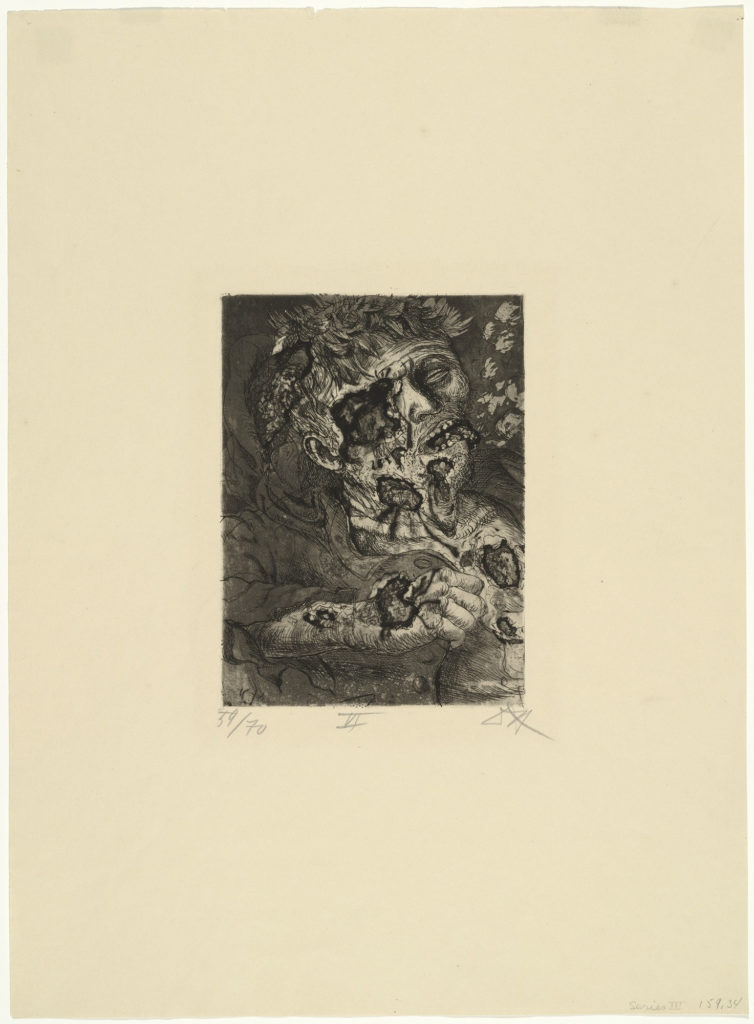

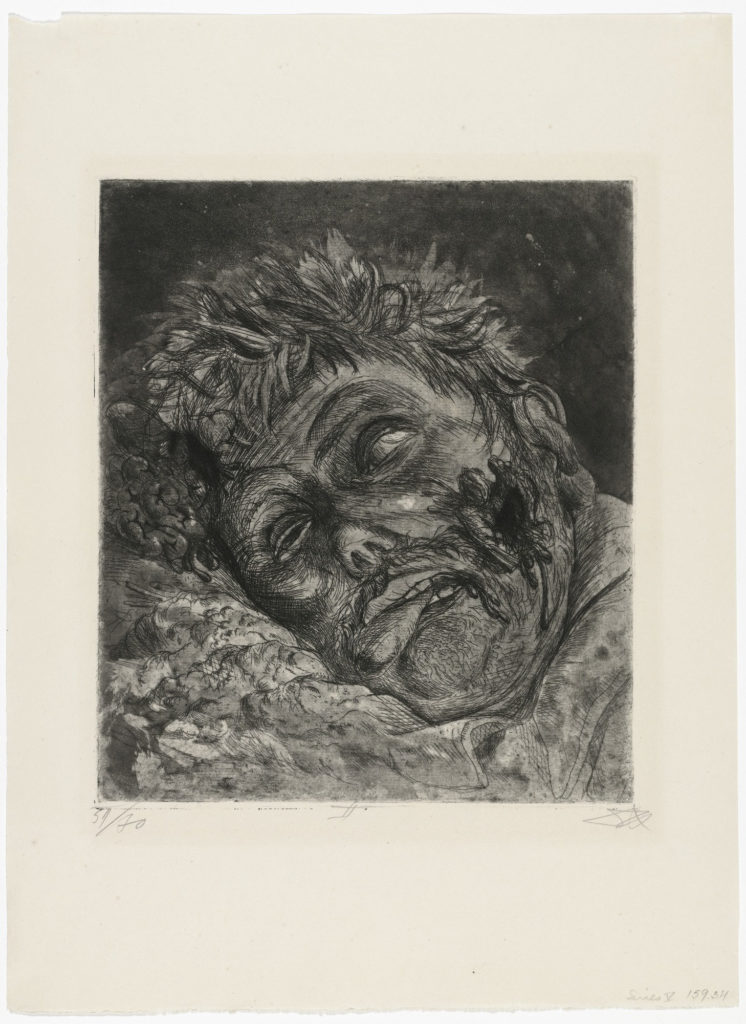

Dix made violent, stressful, and sharp lines as a result of his Cubist and Futurist influences. Moreover, the agony of the trench had a huge impact on him. After the war, he suffered from terrible nightmares in which he found himself back in the trenches among corpses and ruins.

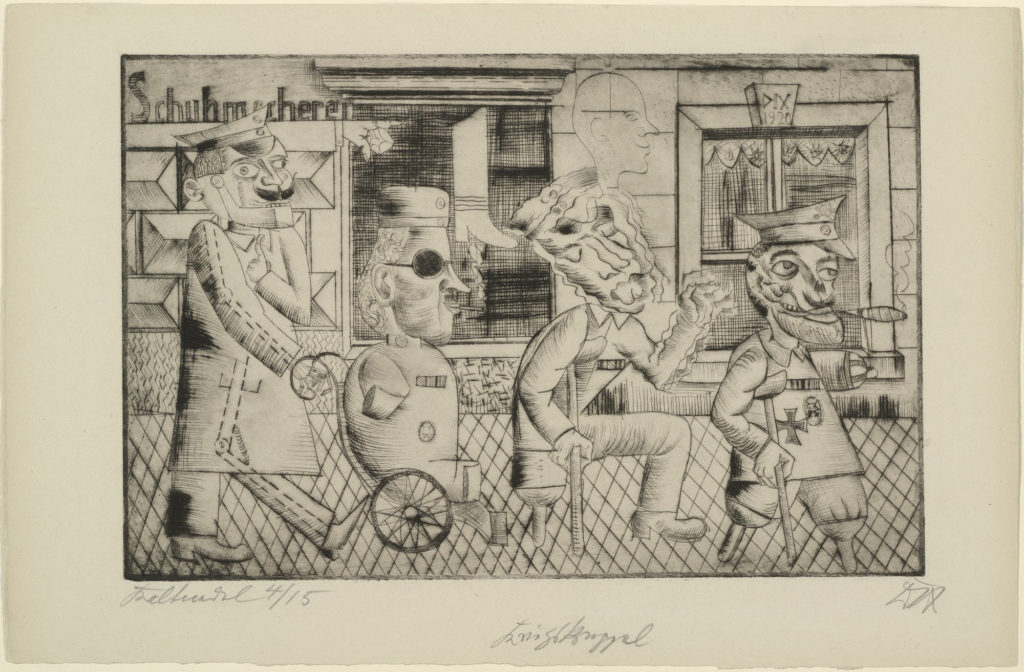

So, he drew the everyday life of the defeated German society, with a bitter and sarcastic point of view. During this time, he learned etching and drypoint techniques, which he used in his series The War (Der Krieg).

Another major source of inspiration for Dix were photographs of wounded soldiers. Their faces were horrifically disfigured and deformed by fragments of bombshells, mortars, and mines. Many of the survivors had to go through multiple surgeries in order to have a more human face again, while others used specially fabricated masks so they could have a basic social life. Dix asked a photographer friend to magnify such photos for him.

Otto Dix made The War series during the winter of 1923-1924. It consists of 5 portfolios, each containing 10 etchings and drypoints. The feeling of these is nightmarish; besides, “corpses are faceless”. Dix didn’t use any color in these images. By this he sought to transport the viewer to the war zone; the battlefield, crippled soldiers, prostitutes, disease, hunger, and gas masks were common themes in these etchings. The War was published in 1924 on the anniversary of the outbreak of World War I and was exhibited in 15 German cities that year.

I did not paint war pictures in order to prevent war. I would never have been so arrogant. I painted them to exorcise the experience of war. All art is about exorcism.

Otto Dix, National Gallery of Victoria

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!