5 Ultracontemporary Artists Redefining the Korean Art Landscape

The dynamic South Korean art scene is quickly becoming one of the most prominent globally, blending rich traditions with cutting-edge innovation. And...

Carlotta Mazzoli 13 January 2025

David Hammons: Body Prints, 1968-1979, at The Drawing Center (closes May 23) and Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art (closes June 27) are currently on view at institutions just steps away from each other in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood. In each of these exhibitions the use of the artist’s body to make art resounds from one space to the next.

The Drawing Center is currently presenting a selection of thirty-two body prints created early in Hammons’ (born 1943) career while he was living in Los Angeles, California. Photographs documenting the artist’s process illuminate the performative use of his body to create these works. The retrospective of Laura Aguilar’s (1959-2018) career is a comprehensive look at a Chicana, queer, Los Angeles-based artist and self-taught photographer who used her nude body as a subject for self-portraits in nature. Aguilar’s work is an exploration into the complexities and complications of marginalization.

The David Hammons exhibition at the Drawing Center is the first of its kind. Laura Hoptman, curator and executive director, had been sitting on the idea to mount a show of these early works for many years. Viewing these thirty-two prints together is a monumental experience given that this body of work has never been shown as a group. It is quite the curatorial feat, given that many of these prints were either sold or given away by the artist during the period of production. Since then, these prints have found their way into numerous and prominent public and private collections, with many remaining to be discovered. Meanwhile others continue to be discovered on the secondary art market.

Hammons created these mono prints while living in Los Angeles. At the time he was surrounded by a community of Black artists and activists who were instrumental in the Black Art Movement of the late 1960s/early 1970s. The production of body prints by Hammons reflect the creative milieu of the time when artists were exploring new paths for artistic expression through performance, assemblage, installation and other unconventional means. They sought to develop an aesthetic that was authentic to their Black experience and identity. In addition to these immediate influences, the use of white, female bodies as living paintbrushes by the mid-twentieth century French artist Yves Klein was also of consequence and highlighted in an exhibition of both artists in 2014.

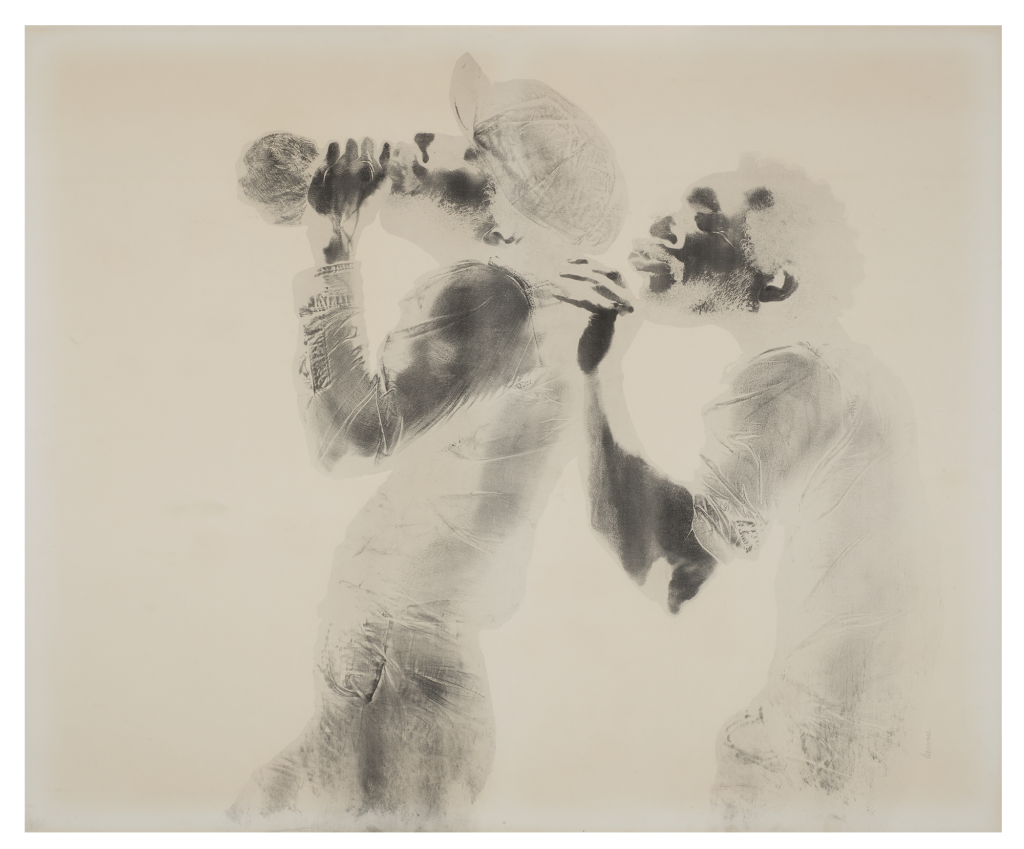

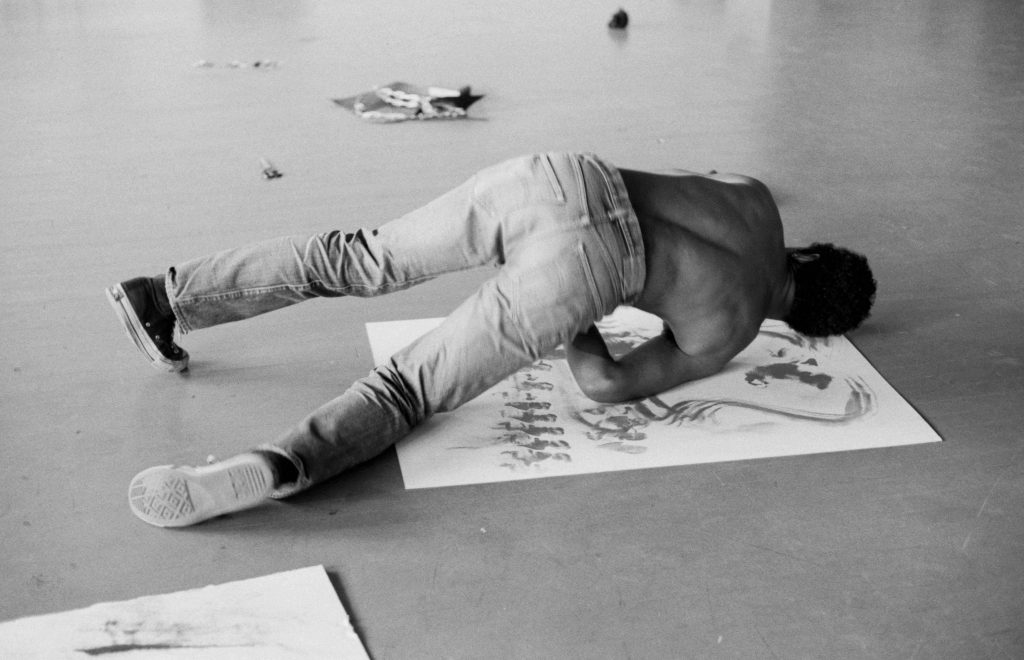

Hammons created these mono prints by greasing up a part of his body with baby oil or margarine and then pressing that body part onto a piece of paper. He then sifted powdered pigment onto the areas where his body came into contact with the paper, a process that made the imprint visible. In addition to pigment, the artist used other materials and built up the images through collage and silk screen. He did not limit the use of his body as instrument to just paper but used found materials such as windows or doors in a similar manner.

Hammons used his own body for most of these prints, but in some instances others were invited to participate in the process. Such was the case with fund raisers that were held in the 1970s to benefit the Just Above Midtown (JAM) art gallery in Manhattan. At these events, the artist, with the assistance of JAM founder Linda Goode Bryant and artist Senga Nengudi, applied baby oil to the bodies of participants who then imprinted their bodies onto sheets of paper. These prints were sold to support a gallery space created for the exhibition of Black artists. However, it is worth noting that Hammons never used this space to formally exhibit his body prints.

In addition to this dynamic collection of body prints, The Drawing Center is showing photographs documenting Hammons’s studio practice during this period. These photographs were taken by Bruce W. Talamon, a long-time friend and collaborator. The photographs illustrate the performative aspect of the Hammons’ process which involved awkward positions to achieve the desired compositions. He also used his own body to create images of male figures shown in a variety of situations and arrangements. Exaggerated features and body parts combined with symbolic imagery, such as the American flag, are repeated throughout.

“In an interview in 1986, Hammons told his interlocutor that his aim was to ‘mak[e] sure that the Black viewer had a reflection of himself in the work.’ The body prints are the first example of Hammons making artworks that not only speak to, but also mirror, an intended audience.”

Drawing Papers 144: David Hammons: Body Prints, 1968-1979, The Drawing Center.

The image of the American flag wrapped around a Black body unmistakably references the atrocities, past and present, that continue to take aim at the Black body. Hammons masterfully used his own body to make images that are intentionally layered with meaning and ideas that remain just as potent today.

The Laura Aguilar retrospective consists of seventy works spanning three decades of production. This exhibition was organized in 2017 by the Vincent Price Art Museum, in Monterey Park, California, in collaboration with the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center. This show was guest curated by Sybil Venegas, Independent Art Historian and Curator and Professor Emerita of Chicana/o Studies at East Los Angeles College. It also made stops at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum in Miami, Florida and the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago. The final stop in New York City is at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, a museum whose sole mission is to exhibit and preserve LGBTQ art.

Aguilar was born to a Mexican-Irish mother and Mexican-American father in Los Angeles, California. She identified as a large-bodied, working-class queer Chicana woman. She addressed these aspects of her identity as well as her personal struggle with auditory dyslexia and depression throughout her career. Aguilar confronted the underrepresentation, under-appreciation and limited access that she experienced personally and professionally. While seemingly unsurmountable, the barriers that Aguilar faced over the course of her lifetime informed her artistic endeavors.

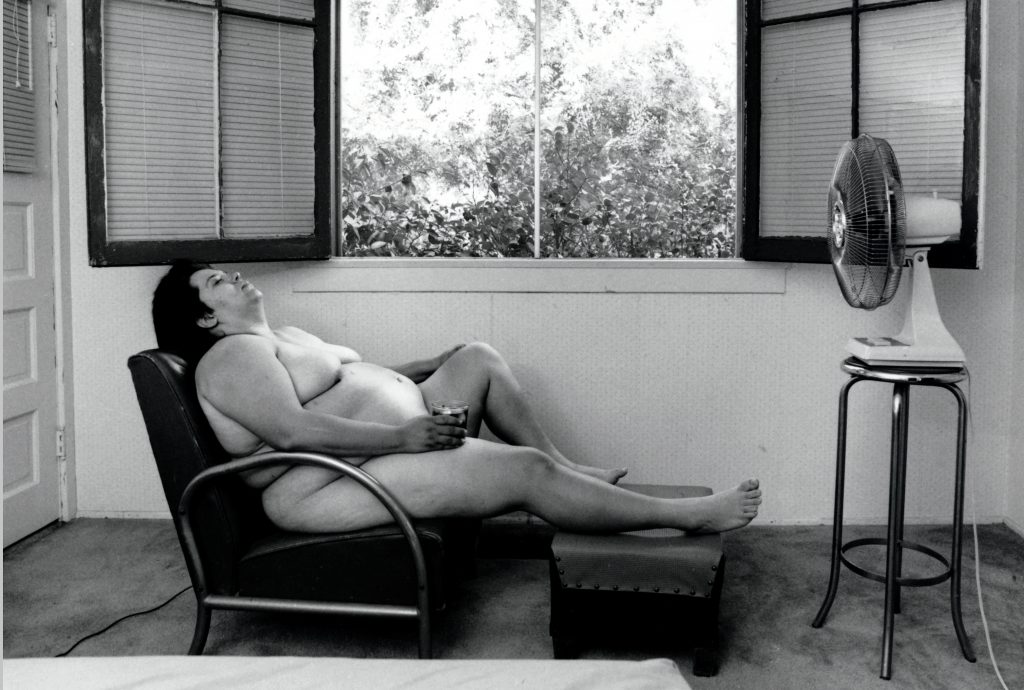

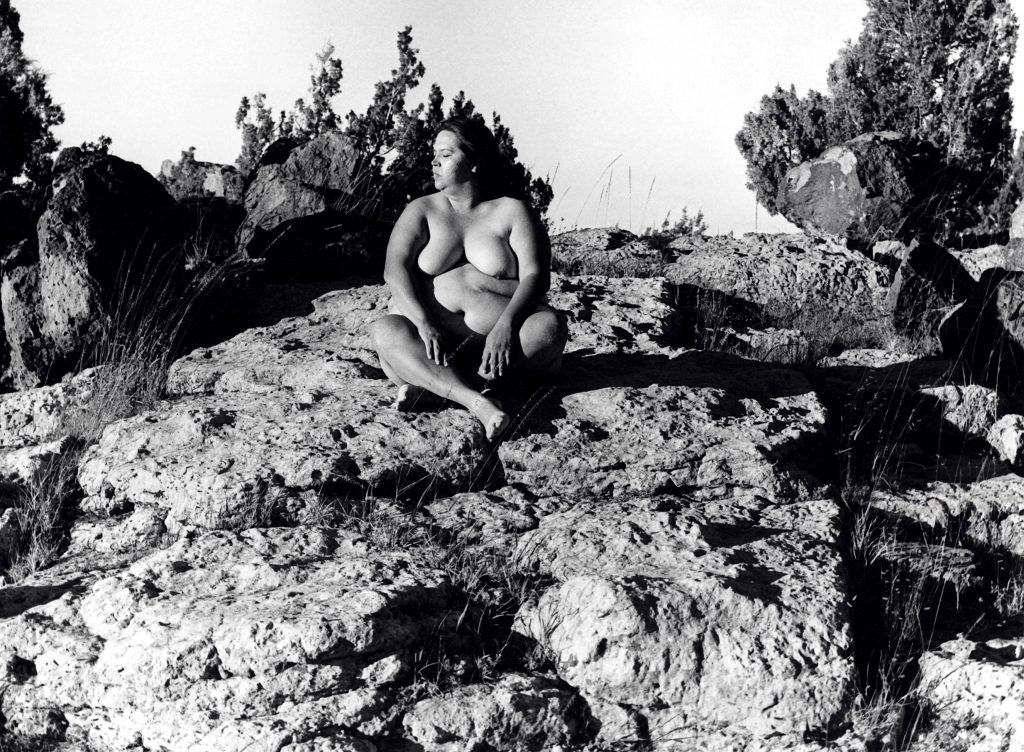

The Aguilar retrospective includes early series of works that eventually led to the photographs most often associated with this artist. By the end of the 1980s, Aguilar turned the camera on herself, creating photographs that made for some of the most striking images of the late twentieth century. With regard to the difficulties that the artist had with reading, writing, and understanding others in conversation, the pivot towards her body as subject, as a means of connecting with the viewer and the landscape, is a masterful balance of fragility and strength.

“I think a lot about why I photography myself nude I know it started at a place of shame . . . before I don’t think I really every look at myself no one else look at me notice me so I just pick up that I don’t exist. . . . Now somedays I find myself just standing there looking at myself naked in front of the mirror thinking, looking to find something new to photography and there come this big smile on my face and I think yes you are crazy and its ok.”

Laura Aguilar, letter to photographer and teacher Joyce Tenneson.

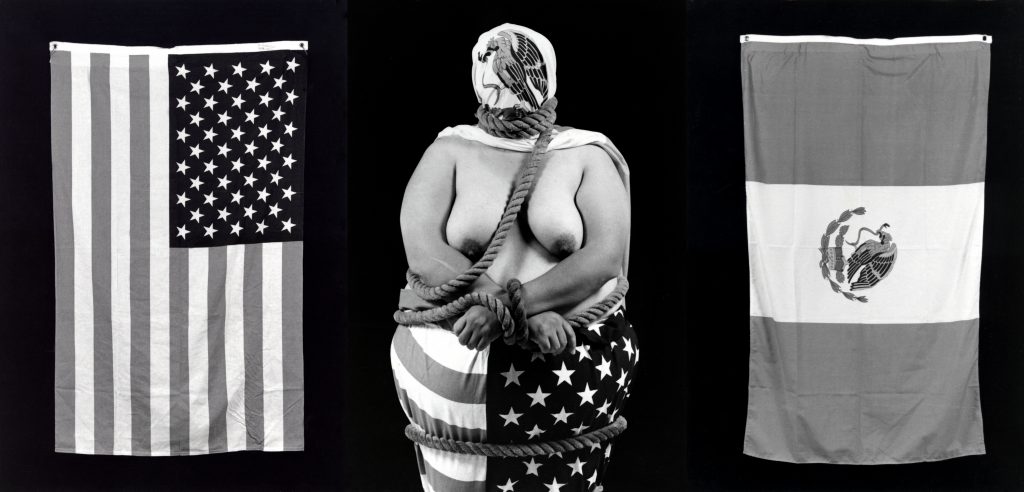

In Three Eagles Flying, 1990, the bottom half of Aguilar’s nude body is wrapped in the American flag and her head is wrapped in the Mexican flag. A rope binds her hands together, winds around her body, and wraps around her neck in the style of a noose. On either side of her hang the flags of each country, to which she felt simultaneously connected and disconnected. Thirty years later this image has not lost its relevance. The viewer is left to understand this naked body as bound and suffocated, a body whose personhood has been taken away; her ability to speak, advocate for herself is not an option. This is a body whose agency has all but been eradicated by the objects that are representative of nationalism, patriotism, and oppression.

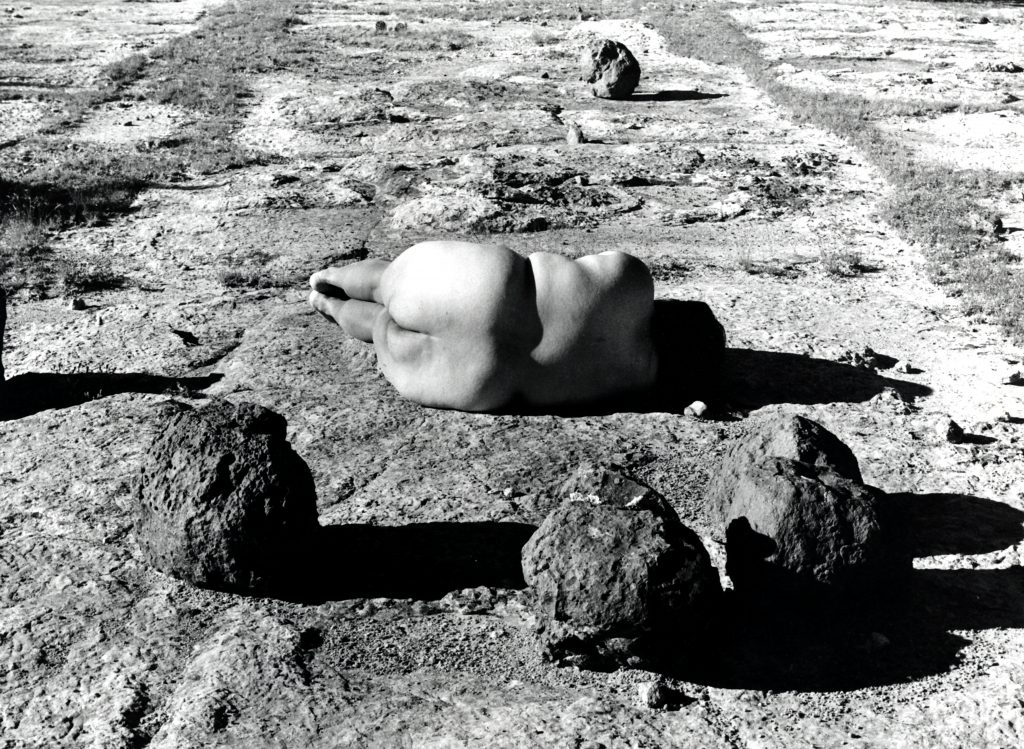

In the mid-1990s, Aguilar photographed herself in the nude for her Nature Self-Portraits. This series of black and white photographs show the artist in positions that mimic her natural surroundings. Liberated of clothing and other restraints, physical and psychological, the natural curves of the artist’s body are harmonious with the landscape. These environments were comforting places where the artist could be vulnerable and let her guard down. In these landscapes, her body is in contact with the earth and bathed in sunlight. The feeling of the sun on Aguilar’s body made up for the lack of touch and intimate experiences not felt in real life. Even though she formed connections within her community, lingering themes of disconnect are evident throughout.

Aguilar continued to photograph her nude body and others in nature, eventually switching to color for her Grounded series from 2006. In these later photographs the formal and spiritual connections between the artist’s body and nature is further enhanced. Sadly, three years ago her body succumbed to diabetes and her life ended at the age of 58. Aguilar left behind a body of work that will continue to influence future generations. This retrospective is evidence that Aguilar had plenty to say and maintained ultimate control in her choice of expression and the use of her body.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!