The Frank Stella You Thought You Knew

You may know Frank Stella from the brightly colored, shaped canvas paintings in his Protractor series from the late 1960s to early 1970s. However,...

Marva Becker 11 July 2024

Damien Hirst – a prominent Young British Artist (YBA) and now a billionaire – creates sculptures, paintings, and drawings. In all of these forms, his work challenges the boundaries between art, science, and religion. His 2019 show Mandalas at the White Cube Mason’s Yard, London explored questions of death, life, and beauty and put at the center one of Hirst’s favorite motifs: the butterfly.

Most people know Hirst because of his Natural History series. These artworks present bodies suspended in formaldehyde, creating a “zoo of dead animals.” Hirst’s questioning of biological existence and death takes a literal form with Mandalas.

Mandalas are geometric designs that aid the viewer’s meditation. They try to represent a microcosm of the universe – Hirst is not an artist who shies from daring ideas. Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, or Shinto traditions all use Mandalas. This means that the Butterfly Mandalas (in contrast to the Kaleidoscope paintings) link to Eastern rather than Western traditions.

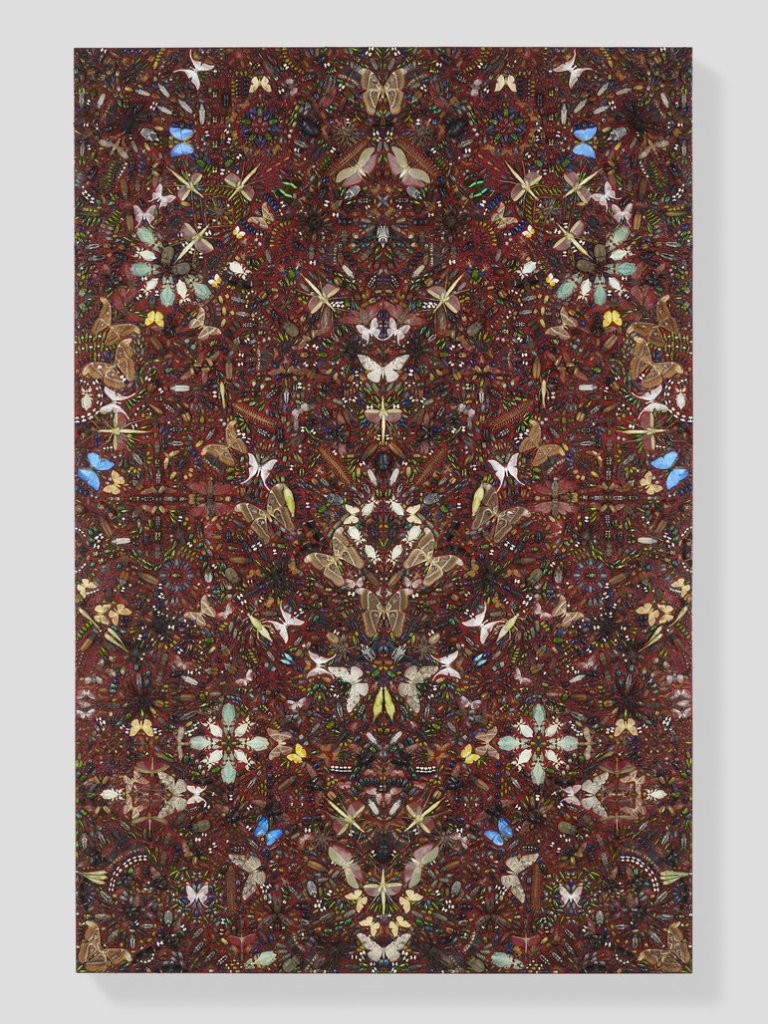

Hirst’s new Butterfly Mandalas are large-scale concentric paintings featuring one of his most well-known motifs, the butterfly. The mandalas, on huge glossy canvases, are concentric patterns of hundreds of butterfly wings. The predominantly circular pieces are incredible in their intricacy. The complex detail becomes more mesmerizing as a result of the particular color palette of each piece.

The butterfly retains its form in death and so it embodies the fascination around mortality. The Greeks used the butterfly to symbolize the soul and in Christian imagery, the butterfly is an image of the resurrection. So, it is no wonder that butterflies fascinate Damien Hirst, who has described the butterfly as a “universal trigger.”

Hirst’s prolonged exploration of the life cycle of the butterfly … is one of the most thoroughgoing and many-sided conceptual projects sustained by any contemporary artist.

Rod Mengham, in the catalogue to accompany the exhibition

Butterfly Mandalas literally gloss and pin back fragility. Stuck into bright and popping household gloss paint the butterflies become eternalized. Each mandala draws the eye to the single, small, butterfly at their center. The viewer is forced to meditate upon the bodiless butterfly and all the ideas that it suggests.

I’ve got an obsession with death … but I think it’s like a celebration of life rather than something morbid.

Damien Hirst cited in Damien Hirst and Gordon Burn, ‘On the Way to Work’ (Faber and Faber, 2001), 21.

Their wings have been dissected from their bodies, but are placed to give an impression of their former corporeality. Like the background paint, the colors of the wings shine bright. Exaggerating this, the uniform placement of multiple butterflies (each ring of the same species) heightens the sense of idealized beauty. Some of the butterflies are very large and obviously rare. Alongside these are more common admiral butterflies; altogether the wings in their mandala arrangement become transfigured into something extraordinary.

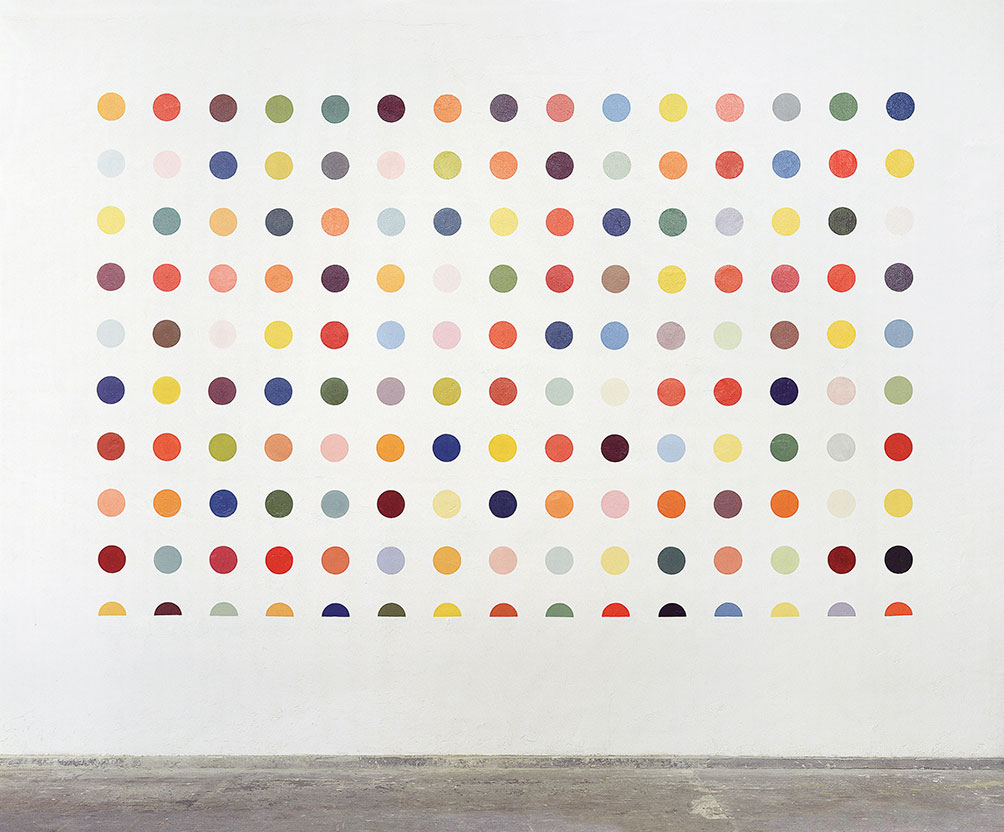

Hirst has worked with butterflies consistently since as early as 1989. His iconic Kaleidoscope series (2001 – present) also use butterflies. Victorian tea trays were the inspiration for their design but their dramatic titles make them much more philosophical.

The Kaleidoscope pieces have spiritual titles, some from the book of Psalms. Many deliberately evoke the grandeur of stained-glass windows.

The Mandala series once again uses some religious titles but in a possibly less pointed manner, like Deity, The Creator, Martyr, Transfiguration, and Baptists. Other titles of the Mandalas include Dromenon, Obscuritas, and Unveiling, for example. Possibly intended to direct the viewer’s meditation?

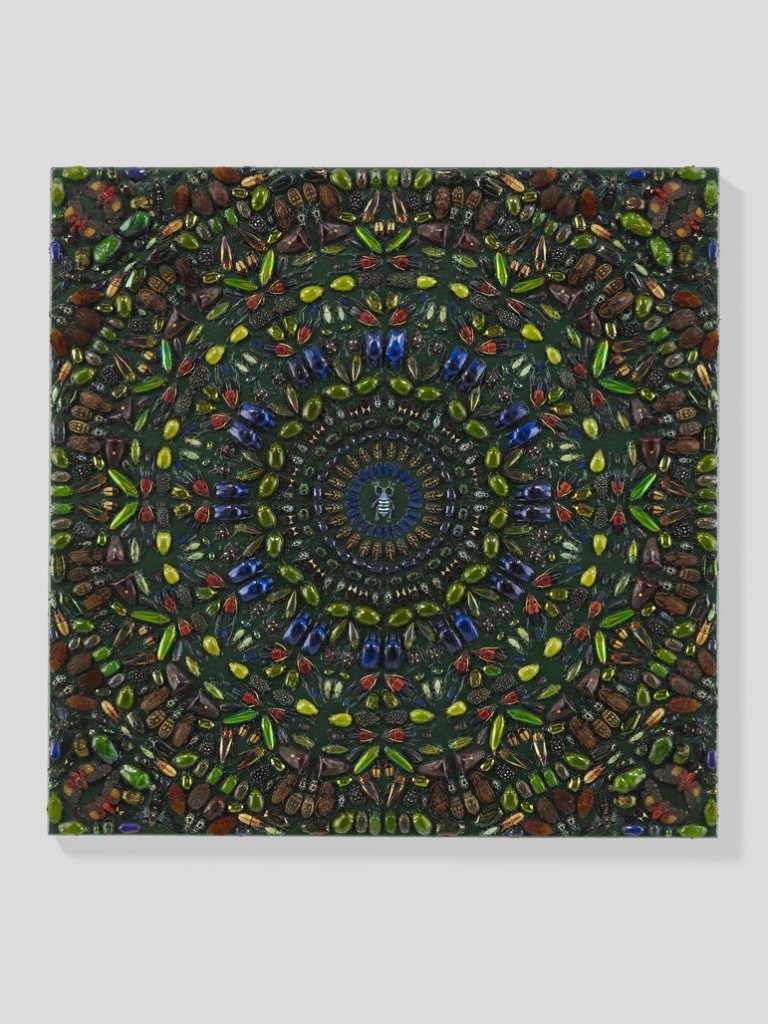

In contrast to the Kaleidoscope and Mandala series‘, Entomology Paintings, which Hirst has been working on since 2009, take their names from Dante’s Divine Comedy. The Entomology Paintings feature not just butterflies but hundreds of insects.

Beautiful and horrific at the same time, you can’t help but be drawn into it, seduced by it, but you want to run away from it.

Damien Hirst in conversation with Tim Marlow, ‘Entomology Cabinets and Paintings, Scalpel Blade Paintings and Colour Charts’ (Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. / White Cube, 2013)

Hirst’s art often necessitates the death of something in order to for it to be looked at. This is not always well received. Like many Young British Artists, his art provokes debate.

In 1988 Damien Hirst was still a student at Goldsmiths. It was in his second year that he organized one of the major initial exhibitions for the YBAs. At the Surrey Docks in London the exhibition Freeze ran from 6 August to 29 September 1988. 16 artists showed their work to an impressive caliber of critics.

In March 1991 Hirst presented a thirteen-foot tiger shark in a tank of formaldehyde at The Saatchi Gallery’s YBA 1 exhibition. It generated colossal press attention and arguably pushed the boundaries of contemporary art. This was the beginning of the Natural History series that truly propelled Hirst into fame.

In more recent years Hirst’s art has become known for making money as well as being shocking.

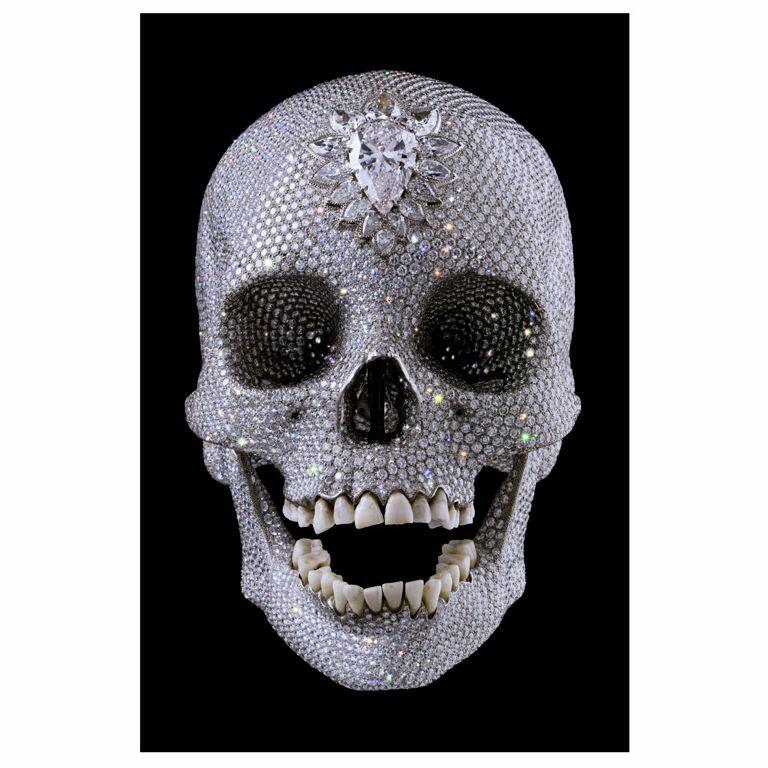

32 platinum plates, 8,601 pavé-set diamonds, and human teeth are the materials in For the Love of God. While Hirst was growing up in Leeds, saying he wanted to become an artist, his mother would exclaim: “For the love of God, what are you going to do next!” The performative sale of the diamond skull at Sotheby’s auction house led to discussions about the concept of media art.

Damien Hirst is a brand, because the art form of the 21st century is marketing. To develop so strong a brand on so conspicuously threadbare a rationale is hugely creative – revolutionary even.

Germaine Greer, writing for the Guardian, 22 September 2008.

Hirst’s dealings with death have always remained a constant, while his monetary value continues to soar.

The Mandalas exhibition was not overtly shocking. It doesn’t do anything too wild – like 2016’s Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable (which was described as “art for a post-truth world” and comes with a documentary available on Netflix). Nonetheless, Hirst’s mandalas continue to captivate, shock, and provoke.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!