Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

Cat at Play is a masterpiece by Henriëtte Ronner-Knip who deserves to have her legacy revised and her fame revived. Art does not need to be radical or revolutionary to be relevant.

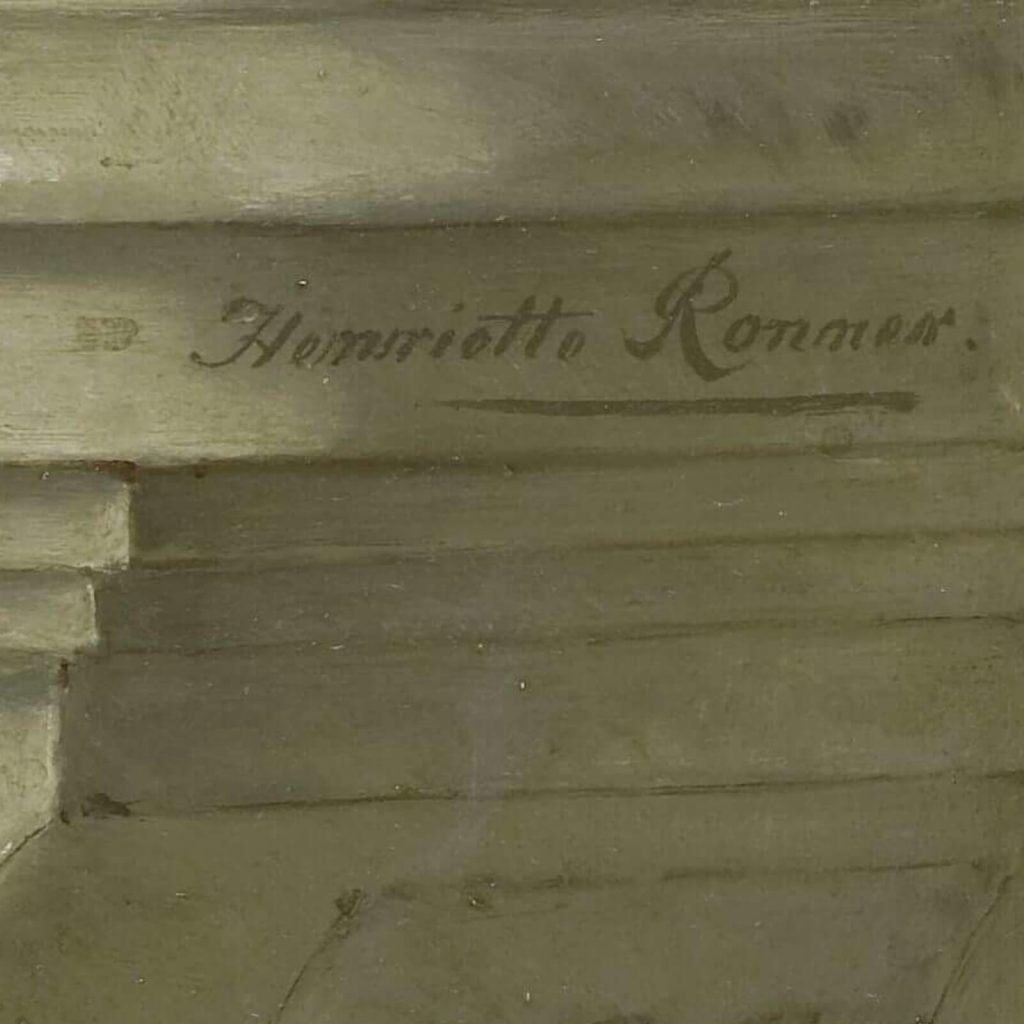

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip (1821–1909) was a woman artist in a field dominated by male artists. She belonged to the late Romantic school that focused on strong emotions, vibrant colors, and bold brushstrokes. Ronner-Knip specialized in portrayals of domestic pets in their bourgeois (middle class) homes. Cats were her favorite subjects: her extensive collection of paintings is dominated by images of cats. Ronner-Knip’s feline paintings frequently evoke viewers’ feelings of sentimentality, curiosity, and playfulness. Cat at Play is a masterpiece of this niche genre. It encapsulates the Ronner-Knip essence.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, 1895, photograph, Cassell’s Universal Portrait Gallery, Cassell & Company, Ltd., London, UK.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip painted Cat at Play approximately from 1860 to 1878. The exact year is undetermined. The painting has small dimensions and would easily fit within a private domestic space. It only measures 32.8 cm high (12.9 inches), 45.2 cm wide (17.8 inches), and 1.8 cm thick (0.7 inches).

The image features a kitten laying on a beveled card table. Domino tiles lay around the cat. A pencil, a paper, and a smoldering cigar add to the scenery. Collectively, the image implies a domino game has just finished, and the players have left the table. The kitten, seizing the vacancy, has jumped onto the surface and seeks the domino tiles as new toys.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Cat at Play is an oil on wood panel. It was a medium quickly losing popularity as stretched canvases became more commercially available to artists in the 19th century. However, oil on panel can be significantly more affordable because it simply requires the sanding and priming of any spare piece of wood. No great skill or expense is needed compared to stretched canvases. Therefore, Henriëtte Ronner-Knip may have preferred oil on wood as her medium because it allowed her to have an affordable pricing for her bourgeois buyers.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip was born in Amsterdam during 1821. Therefore, she was from 39 to 57 years old when she painted her masterpiece. She began painting as a child under the tutelage of her artist-father, Joseph August Knip—decades of experience led to creating Cat at Play. The pensive expression of the cat’s face, the realistic rendering of its fur, and the beautiful coloring of the wooden table are a few masterful details that Ronner-Knip has skillfully captured.

Ronner-Knip believed in live observation of her subjects to glean their physiques and personalities. She would sketch the animals, model them in papier-mâché, and then paint images using the sketches and the sculptures as visual references. Hence, at one point in time, there existed a papier-mâché Cat at Play as a support to the painted masterwork. How interesting!

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Sprinkled throughout the scenery are detailed shadows that are the true magic behind the painting’s realism. A pencil lays in the foreground jutting over the table’s top surface. Its below shadow casts onto the tabletop and then cascades over the beveled edge.

It is impressive how the pencil’s shadow catches the edge’s three rounded surfaces. Greater skill is viewed in the folded paper in the left midground. Not only does Henriëtte Ronner-Knip seize the paper’s dainty border shadow but also its full-bodied reflection in the mirror-like surface of the polished tabletop. Similar illusions occur with the domino tiles scattered across the full sweep of the foreground. They simultaneously cast shadows and reflections, which is a beautiful blending of opposites. Lightness and darkness play together with the same playfulness as the kitten with the dominoes.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Some viewers may dismiss Henriëtte Ronner-Knip’s feline paintings as boring, banal, and unfashionable. Some complain they are just Victorian kitsch. Pretty paintings for vapid-minded collectors. Just empty delicacy and charm. If these dismissals were true, then the Rijksmuseum would not have acquired the piece in 1907, just two years before Ronner-Knip’s death in 1909, and Ronner-Knip would not have been a celebrated and honored artist who was a member of several prestigious art institutions; who received national awards from Belgium, France, Netherlands, UK and USA; and who was collected by the royalty, nobility, and artistic elite of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Just because modern tastes have changed that does not justify disregarding previous generations’ successes. Art does not have to be avant-garde to be respected. Art can be approachable and enjoyable.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Sadly, because modern tastes have changed so much, Henriëtte Ronner-Knip does not receive the recognition or accolades she received in her lifetime. When Ronner-Knip was featured in the 1895 book Cassell’s Universal Portrait Gallery a small biography accompanied her photograph portrait. It praised her artistic reputation and her “fame which there is little doubt will prove to be enduring.” Ironically, this contemporary praise did not endure. Henriëtte Ronner-Knip is now lucky to be a footnote in the volumes of art history books. Her legacy needs revision. Her fame needs reviving. Cat at Play proves it.

Henriëtte Ronner-Knip, Cat at Play, ca 1860-1878, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Detail.

Cassell’s universal portrait gallery : a collection of portraits of celebrities, English and foreign with fac-simile autographs, London, UK: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1895. Digitized 2007. Accessed 19 August 2022.

“Cat at Play.” Collection. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Accessed 19 August 2022.

Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, and Christin J. Mamiya. Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Jordi Vigué. Great Women Masters of Art. New York, NY: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2003.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!