Angelica Kauffman in 10 Paintings

Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) was a Swiss Neoclassical painter. Despite the prevalent misogyny in the 18th-century art world, Kauffman gained fame,...

Jimena Escoto 30 October 2025

22 December 2025 min Read

Antonio Canova was the most famous European sculptor of the Neoclassical period. Best known today for the pristine perfection of his marble figures, during his lifetime, his tombs and memorials were in high demand. One of his biggest commissions, never realized as he intended, was a huge equestrian sculpture, which for years existed only in plaster pieces. In 2025, Canova’s colossal horse was finally reassembled and exhibited again at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan.

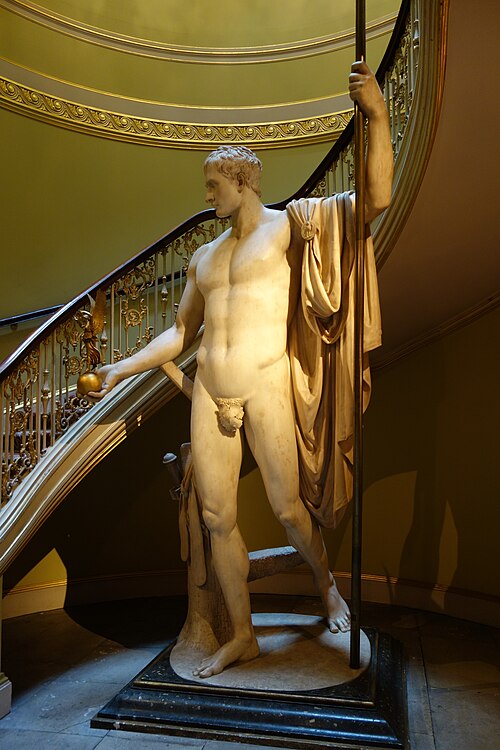

Antonio Canova, Perseus Holding the Head of Medusa, c. 1800, Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

An Italian by birth, Antonio Canova (1757–1822) had a pan-European reputation and a prolific career as a sculptor in the late 18th and early 19th century. His preferred medium was marble, producing everything from portrait busts to idealized figures from classical mythology. Many of his works were based closely on antique originals; for instance, his Perseus Holding the Head of Medusa was modelled on the Apollo Belvedere. His first major success, Theseus and the Minotaur, was actually thought to be a Greek sculpture when first exhibited. However, there is an elegance, almost a prettiness, in Canova’s statues which distinguishes them as Neoclassical.

Canova was an astute businessman. He ran a large studio, which was compared to a factory, both in terms of the number of assistants employed and the specialization of tasks during each phase of production. Initial clay models were routinely cast in plaster, which was more durable and could show clients what the finished work would look like. In the case of the Colossal Horse, the plaster was painted to resemble the intended final bronze.

Antonio Canova, Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, 1802–1826, Apsley House, London, UK. Photograph by Daderot via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Canova met Napoleon on a visit to Paris in 1802. As an Italian, he had no love for the man who had invaded his country and systematically looted some of its most famous artworks back to France. However, Canova recognized power and patronage, and he was encouraged to go to Paris by the Papacy in the hope of securing the return of some of the art.

Napoleon sat for a portrait bust, which would later become the basis of an over-life-size statue of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker. The sculpture was not well received: Canova had represented the French Emperor as an idealized nude. Napoleon, perhaps understandably, found this embarrassing, describing it as “too athletic.” More importantly, by the time the statue arrived in Paris in 1810, the idea that he was a “god of war” or a “peacemaker” was unsustainable. In a final ignominy, the sculpture was sold to the Duke of Wellington after Napoleon’s defeat, and can still be seen in the Duke’s London home.

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, c. 175 CE, Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

In 1807, Canova was commissioned to produce a similarly monumental equestrian sculpture of Napoleon, by the Emperor’s brother Joseph, who had been named King of Naples. It was inspired by the only existing classical example, the bronze statue of Marcus Aurelius in Rome. Napoleon would be shown on horseback in antique armor, riding without stirrups in the Roman style, thus linking him to the emperors of the past.

The plan fell through and, after the restoration of the Bourbon rulers of Naples, the design was adapted to depict Charles III. The sculpture was finished, cast, and erected in 1819, using Canova’s horse and a figure of the king, which may well have been by another artist.

A second plaster horse was then created for a similar monument to Ferdinand IV of Naples. The sculpture was only completed after Canova’s death, the figure of the king being added by Antonio Cali, one of the artist’s pupils. Both statues were placed in the Piazza del Plebiscito in Naples.

The neck and torso of Canova’s Colossal Horse during the restoration process. Photograph by JPS Ilaria Zago. Press materials.

Like the majority of Canova’s plasterworks, the two huge horses became part of the collection of the Museo Civico in Bassano del Grappa. The horses were originally both on display at opposite ends of a gallery. However, the Charles III horse was destroyed during Allied bombing in 1945.

Its scale and the fact that it had been painted green to resemble patinated bronze made the remaining horse something of an anomaly in a collection of small, delicate, and pure white pieces. In 1969, it was broken up into sections and put into storage, largely forgotten about. Only the head remained on display.

The decision to reassemble the horse was taken in 2025. It involved replacing the internal armature with one of non-corrosive materials and constructing a new, stress-proof base. The plaster surface was also conserved.

Antonio Canova, Colossal Horse, 1819–1821, installation view of Eternal and Visionary. Rome and Milan as Capitals of Neoclassicism, 2025, Gallerie d’Italia, Milan, Italy. Photograph by Maria Parmigiani. Press materials.

By undertaking an equestrian commission, Canova was following in a long line of sculptors who ultimately took their inspiration from the Marcus Aurelius monument. He was familiar with Donatello’s Gattamelata, the first large-scale Renaissance iteration. Equally, Canova referenced Greek horses on the Parthenon marbles, which were in the process of being removed to London during this period.

At four meters (over 13 feet) tall, the horse was deliberately designed to be the largest such sculpture in Europe. Canova copied and exaggerated the raised front leg of his horse from the Marcus Aurelius. He gave the horse’s head a sense of drama and emotion with its slight twist, open mouth, and deeply indented nostrils and pupils. At the same time, the vertical neck creates nobility and elegance. The emphasized musculature shows the animal’s power but it also, as in Canova’s figures, idealizes it to create a timeless representation of equine perfection.

Contemporaries remarked how life-like the horse was, and Canova made a large number of preliminary sketches to achieve this. However, he balanced this observation by placing the sculpture within the ideals of Neoclassicism, ultimately creating a heroic symbol of leadership.

Giuseppe Bossi, Napoleon Leaning a Globe, 1806, private collection.

Canova’s horse is one of the highlights of an exhibition currently on show at Gallerie d’Italia in Milan. Eternity and Vision looks at the cultural impact of Napoleonic rule in Italy, 1796–1815, through the work of Canova and lesser-known artists like Giuseppe Bossi—who was a major collector and founded the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan—and Andrea Appiani. 10 sections of painting, sculpture, graphic, and decorative works explore the close ties between Neoclassicism and the Napoleonic regime.

Whilst cities like Florence and Venice found their art plundered by the French, Milan and Rome thrived as cultural centers under foreign rule. Rome remained an international center for art education. Milan’s cathedral was chosen for Napoleon’s coronation as King of Italy, and regalia from the ceremony is on show here alongside Appiani’s portrait of Napoleon as King.

The restoration of Canova’s Colossal Horse plaster emphasizes the range of the sculptor’s work. He is often dismissed as too sweet, too pretty, too perfect. In scale, drama, and effort, his horse tells a different story.

Eternity and Vision. Rome and Milan as Capitals of Neoclassicism is on view at the Gallerie d’Italia in Milan until April 6, 2026.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!