The Ishtar Gate: A Gateway to Babylonian Grandeur

The Ishtar Gate, one of the most iconic remnants of Ancient Mesopotamia, stands as a testament to the grandeur of the cradle of civilization. This...

Maya M. Tola 24 July 2025

Nestled in the plains of present-day Pakistan and northwest India lies one of the world’s most enigmatic ancient societies: the Indus Valley Civilization. This remarkable era left behind cities so advanced in urban planning, sanitation, and organization that they continue to impress modern engineers. The intrigue deepens with the many unanswered questions it left behind, including its undeciphered script, ambiguous social structure, and haunting and unexplained decline.

Named after the Indus River, this civilization thrived in the northwestern regions of South Asia across modern-day Pakistan, northwest India, and parts of eastern Afghanistan. Its key cities, like Harappa and Mohenjo-daro, took root in lands blessed with natural water sources and fertile soil. Seasonal flooding provided predictable irrigation, fueling agriculture and trade.

Brick mounds in the Indus Valley were first noted in 1829, but their significance remained unclear, with many believing them to be remnants of ancient castles. A breakthrough came in 1912, when British civil servant John Faithfull Fleet discovered seals inscribed with an unknown script while working with the Indian Civil Service. These artifacts hinted that a significant and previously unidentified civilization had once thrived in the region.

This discovery prompted Sir John Hubert Marshall, then Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, to begin formal excavations at Harappa in 1921, followed by Mohenjo-daro in 1922. The findings revealed a remarkably advanced urban culture, ultimately leading to the identification of over 1,500 Indus Valley sites across India and Pakistan.

Seal from the Indus Valley Civilization, ca. 2000 BCE, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH, USA.

The Indus Valley Civilization demonstrated extraordinary levels of organization, reflecting a strong centralized authority. Cities were constructed using standardized baked bricks, and there is compelling evidence of a regulated trade system supported by uniform weights and measures. These tools of commerce, often made of chert or stone, were consistent across vast regions, indicating a high degree of coordination.

Thousands of seals, many inscribed with undeciphered script and symbolic imagery such as horned figures, suggest administrative or ritual functions in overseeing trade and governance. This was a society in which commerce, construction, and perhaps even spiritual life were managed with remarkable uniformity.

Standardized cubical weights, Mohenjo-daro, ca. 2600–1900 BCE, British Museum, London, UK. Photograph by Zunkir via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-4.0).

The Indus cities of Mohenjo-daro and Harappa stand out as exceptional examples of ancient urban design. These sprawling settlements were meticulously planned, featuring grid-patterned streets, standardized brick construction, and advanced drainage systems, all of which were centuries ahead of their time. Streets intersected at precise right angles, and many buildings were strategically oriented to capture prevailing winds, providing a natural form of air conditioning. This level of civil engineering reflects not only practical ingenuity but also a sophisticated understanding of environmental adaptation and urban functionality.

Sherd, ca. 3000–2500 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The Indus Valley Civilization built one of the earliest urban sanitation systems in the world. Many homes had indoor toilets connected to covered drains that emptied into street-level sewers, demonstrating a level of hygiene far ahead of its time. These toilets were built with chutes that led directly into the public sewer system.

Homes were often multi-story, with private wells, courtyards, and direct links to a central drainage network. Drains from houses were connected to larger public drains running along the main streets. Cities also had brick-lined canals, manholes, and other features for handling waste.

Ceremonial Vessel, Harappa, ca. 2600–2450 BCE, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

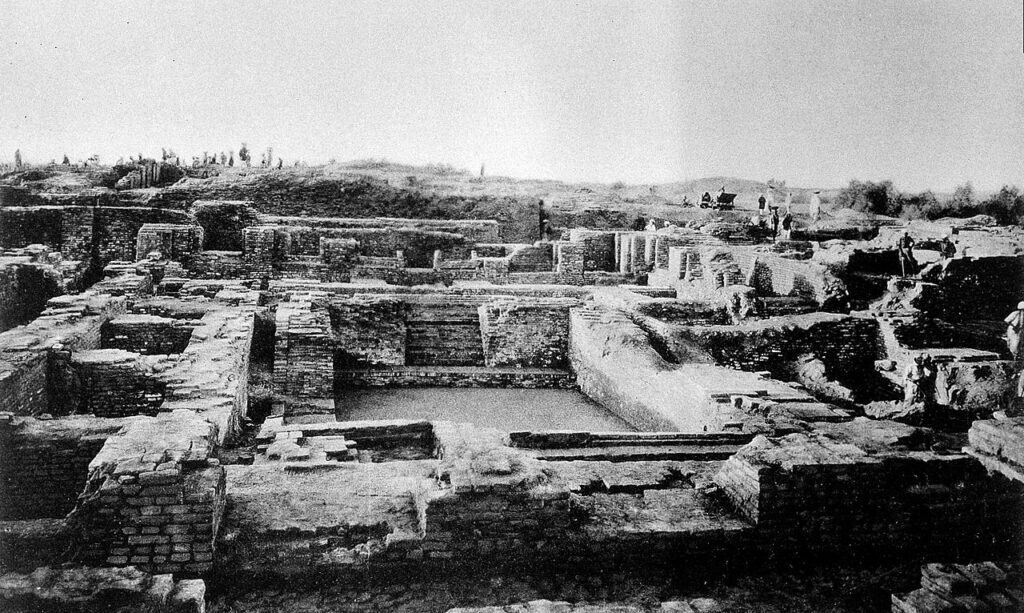

One of the most famous structures of the Indus Valley Civilization, the Great Bath is a name coined by archeologists, as its original purpose and name remain unknown. Located in Mohenjo-daro, it stands as one of the earliest public water tanks in the ancient world. Built alongside wells, reservoirs, and bathing platforms, it reflects the central role of water in both daily life and possibly ritual practice.

While the true function of the Great Bath is uncertain, many scholars believe it was used for ritual purification, based on its central location. Some historians draw connections to later Indian traditions that emphasize cleansing rituals.

The Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro, archeological excavations between 1922 and 1927. Wellcome Collection.

The Indus Valley Civilization had a thriving economy based on agriculture, craftsmanship, and long-distance trade. They cultivated wheat, barley, peas, cotton, and dates, and domesticated animals such as cattle, buffalo, and elephants.

Indus artisans excelled in bead-making, pottery, terracotta figurines, and shell carving. They were among the first in the world to spin cotton into thread, a skill that may have later spread to the Mediterranean world. Their craftsmanship is especially evident in the production of seals engraved with animal motifs and symbolic imagery.

There is clear evidence of trade with Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) as early as 3500 BCE, through both land and sea routes. Indus goods such as carnelian beads and cotton textiles have been found in Ur and Sumer, showing that the civilization was deeply connected to regional trade networks and played a significant role in early global commerce.

Reclining mouflon, ca. 2600–1900 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The Indus script appears on over 4,000 artifacts, including seals, pottery, and tablets. It features a combination of animal symbols such as bulls, elephants, and unicorn-like figures, as well as geometric patterns. Despite extensive study, the script remains undeciphered, making it one of the great mysteries of the ancient world and a source of endless fascination for archeologists, linguists, and South Asian history enthusiasts alike.

All that is known about the Indus Valley Civilization comes from archaeological evidence, as no bilingual inscription (like a Rosetta Stone) has been discovered. This lack of linguistic access significantly (and heartbreakingly!) limits our understanding of their beliefs, governance, and social structure.

Pashupati Seal, Mohenjo-daro, ca. 2600–1900 BCE, National Museum of India, New Delhi, India. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Life in the Indus Valley appears to hint at an advanced civilization. Artifacts indicate that personal adornment was common. Men and women wore items such as necklaces, bangles, and earrings. Terracotta figurines, often interpreted as fertility symbols, suggest that women may have held important roles in both domestic and spiritual life.

The discovery of toys such as wheeled carts, animal figurines, and spinning tops demonstrates a focus on children and leisure, offering a rare glimpse into the everyday experiences of this ancient culture.

Carnelian bead, ca. 2900–2350 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

The religious beliefs of the Indus Valley Civilization remain uncertain, however, archeological evidence suggests a focus on natural forces, sacred animals, and possibly deities resembling a proto-Shiva or Mother Goddess figure. Although no large temples or religious structures have been discovered, the presence of ritual bathing sites and figurines points to established spiritual practices. Worship may have centered on fertility and nature-related symbols, hinting at early links to later Hindu traditions.

Small toy whistle, 3000 to 2500 BCE, Brooklyn Museum, New York City, NY, USA.

The people of the Indus Valley Civilization had a distinct genetic identity, separate from their later Vedic descendants. They lived before the arrival of groups such as the steppe pastoralists from Central Asia, who introduced Vedic culture and Indo-European languages that helped shape the next phase of South Asian civilizations.

The Indus Valley population descended from a blend of two ancient groups: indigenous South Asian hunter-gatherers, who had lived in the region for thousands of years, and early farmers from the Iranian Plateau, who migrated into the subcontinent and mixed with local communities.

The Great Bath, Mohenjo-daro. Photograph by Soban via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

The decline of the Indus Valley Civilization began around 1900 BCE, and by 1300 BCE, many of its cities were completely abandoned. Scholars have proposed several possible causes for this gradual collapse, including climate change, shifting river systems such as the drying of the Saraswati or Ghaggar-Hakra River, and environmental disasters like floods or droughts that may have devastated agriculture. A massive earthquake may also have altered river courses and disrupted settlements. Some theories suggest that migrating groups from the Caucasus region could have contributed to the decline. The archeological record suggests their decline likely unfolded slowly over time.

Steatite seal with inscription in Indus script along with impression, British Museum, London, UK. Photograph by Zunkir via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Indus Valley Civilization remains one of the most compelling and enigmatic chapters of human history. While much about it continues to elude modern understanding, evidence suggests that aspects of its culture may have endured through eastward migrations, shaping the later Vedic civilization and influencing the foundations of subsequent Indian traditions.

Its legacy survives both in the enduring mysteries it left behind and in the subtle threads of continuity woven into South Asia’s ancient past. Perhaps the greatest hope lies in the eventual decipherment of its script as such a breakthrough could unlock an entire lost chapter of antiquity.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!