Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

Lucian Freud (1922-2011) is regarded as the pre-eminent British figurative painter of the last 60 years. Francis Bacon, two decades older, and David Hockney, a decade younger, are his main rivals. For years I hated Freud’s paintings of huge, misshapen bodies in improbable postures, done with coarse hogshair brushes and heavy impasto; masses of thick white paint with cold blues, greens and browns. Freud’s nudes in the last decades of the century dramatically challenged conventional erotic associations with naked flesh in art. But an exhibition of 56 of his self-portraits at the Royal Academy in London showed how powerful, disturbing and accurate his work really is.

His early self-portraits reveal an exceptionally handsome man, clear skin largely white and pink with glossy dark hair; touches of blue, painted with a fine brush, often with that sidelong stare that self-painting necessitates. No lines on the face, the fine sable brush strokes making the skin seem taut and tense. His paintings of the 1940s and 1950s have that precise, detailed, hallucinatory character we associate with some Surrealist painters. Like Rembrandt, Freud painted himself time and again through an active career of over 60 years.

But the full-length portrait of his naked body, Painter Working, Reflection (1993), painted when he was 71 years old tells another truth about the body and it is emblematic of his practice since the 1950s. Freud refuses the word “nude” and goes against art history by painting his subjects “naked”, with all that word’s connotations of exposure.

The models, friends and family members whom he paints, adopt their own poses and he stands up to paint them, usually taking months and working every day. For this self-portrait Freud adopts a gladiatorial pose, his brush held like a broadsword as though in combat with himself, though the plain background and lack of perspective make him seem unbalanced in his unlaced slippers. Exposed to us is a sinewy body, impastoed with thick strokes of grey-white and brown paint, head thrust forward and eyes fixed on the self, both internal and external. Not even the aged Rembrandt subjected himself to such visceral self-scrutiny.

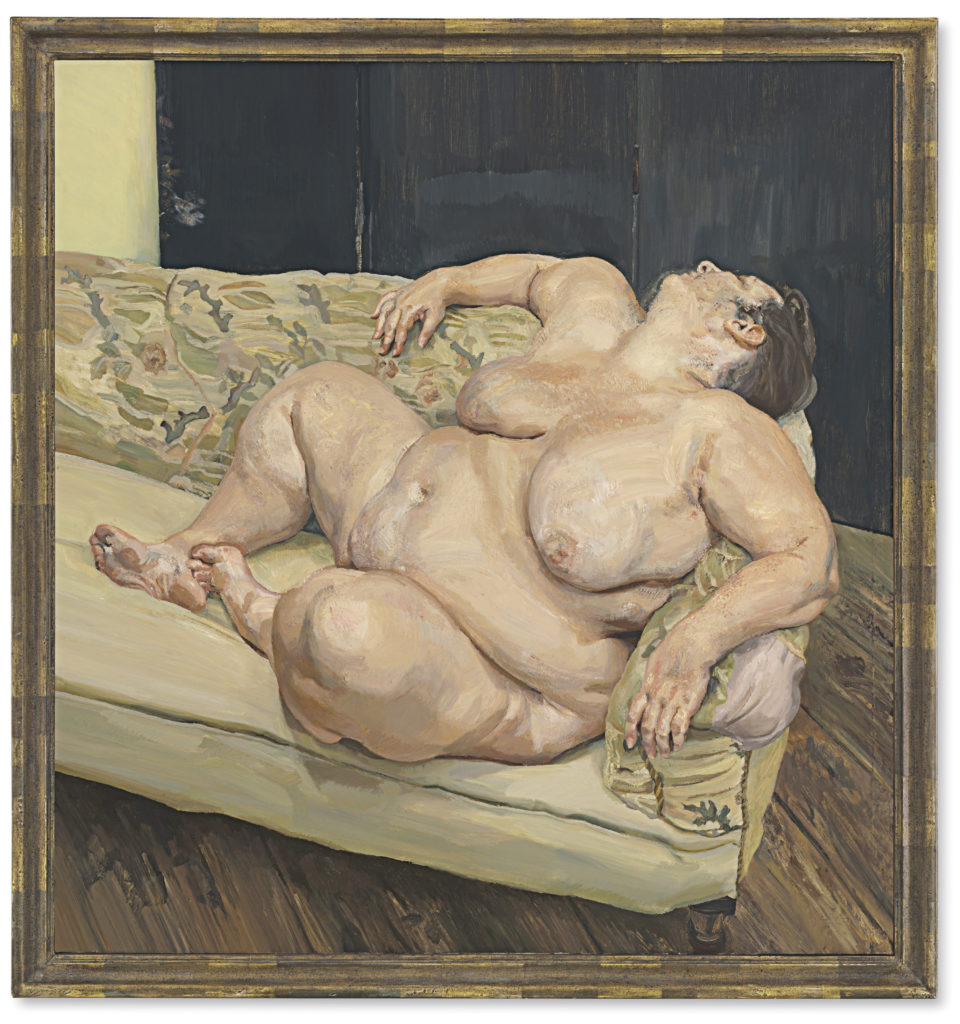

Reflection (Self-portrait) 1985 is limited to his head and shoulders and captures the essence of Freud’s work at the height of his powers. It doesn’t have the overpowering bulk of the enormous fleshy portraits, like Benefits Supervisor Resting, (1994) which made him famous by the end of the century and which sold in 2015 at Christie’s for $50 million.

Reflection is a tonal painting with a palette ranging from patches of light-reflecting white on the nose and chin, through brown to the shades of grey brush strokes forming the background. Conventionally in painting skin is pink, but only the ears are that color in this portrait, and there seems to be just one brush stroke of pink on the collarbone, set against the darkest shadow of the portrait. The hair still has the vibrancy of the earliest self-portraits, perhaps a touch of vanity, but the face is almost gaunt with dark hollows against the varied, shiny brown tones of the rest of the skin. Freud is said to wipe clean his brush after every brushstroke and this may account for the camouflage-like dark and light stripes of the forehead.

But it is the eyes which are the most suggestive part of the painting. Are they blue against the dull whites? Do they suggest a self-doubt where most of the portraits in the exhibition suggest assertiveness, arrogance, even? Does the slight angle of the head suggest a certain wariness? A reluctance to reveal too much?

The title is ambiguous: is this a man reflecting on his image or just reflecting it back to himself noncommittally? Freud’s face appears in miniature in several paintings of other people and his feet or his shadow in others. Freud had a reputation as a womanizing, aggressive man – one self-portrait in the Academy exhibition shows him with a black eye received from a taxi-driver – and in his early portraits some of his female sitters appear tense and anxious, struggling to retain their own identity before his relentless gaze.

‘The task of the artist is to make the human being uncomfortable” Freud said and in the massive nudes upon which his reputation is built his models look as uncomfortable as I used to feel just looking at them. But the late self-portraits suggest a more existential discomfort akin to Shakespeare’s perception of humankind as no more than a “poor, bare, forked animal”. The portrait of the artist reduced to its essentials.

Author’s bio

Philip Simpson left school at 16, worked in various jobs and was obliged to do national service in the military before going to university. Most of his professional life concerned media education in one form or another. For ten years he was Head of Education at the British Film Institute and for a further ten he was Head of the Department of Radio, Film and Television at Canterbury Christ Church University. Between 2005 and 2016 he was a voluntary guide at Tate Britain and Tate Modern. He acted as a guide on private tours of major exhibitions at the Tate, including exhibitions on the work Mark Rothko, JMW Turner and Henry Moore.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!