5 Artists Flirting with Nazis

When it comes to art and Nazis, attention often goes to those artists persecuted as creators of so-called “Degenerate Art” or robbed of their...

Jimena Escoto 5 February 2026

29 December 2025 min Read

The invention of the collapsible paint tube in the mid-19th century revolutionized the art world with a single squeeze. What had once required laborious preparation—grinding pigments, mixing oils, storing paint in fragile bladders—suddenly became portable, durable, and ready to use. For the first time in history, artists could leave the studio with unprecedented freedom and paint en plein air, chasing light and color in real time. This little metal marvel didn’t just change how painters worked; it reshaped the way they saw the world and helped ignite an entire movement that would transform art forever.

Two centuries ago, becoming a celebrated artist in Paris meant securing a place within the Academy—the esteemed École des Beaux-Arts. There, students trained under the most revered masters, perfected their techniques by copying the Old Masters, and vied for a coveted spot at the annual Paris Salon, where their work would be scrutinized by the most influential figures of society. As Pierre-Auguste Renoir once wrote to his close friend Paul Durand-Ruel, art collectors “won’t buy even a painting of a nose if the painter is not at the Salon.”1

But entering the Academy was another challenge entirely. An artist had to pass its formidable gatekeepers, prove themselves worthy of painting from live nude models—a privilege reserved for men—and demonstrate their skill through grand historical or mythological scenes, not everyday subjects. And even then, acceptance was far from guaranteed.

Thomas Gainsborough, Romantic Landscape with Sheep at a Spring, c. 1783, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK.

Historical and mythological scenes often called for sweeping landscapes and dramatic outdoor settings. But where did artists find inspiration for such imagined worlds?

One vivid example comes from Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788), who is said to have painted by candlelight at night, using improvised tabletop models crafted from everyday household items. His miniature landscapes included stones, shards of mirror, bits of fabric—and even clusters of broccoli—arranged to mimic rolling hills, reflective water, and trees swaying in the wind.

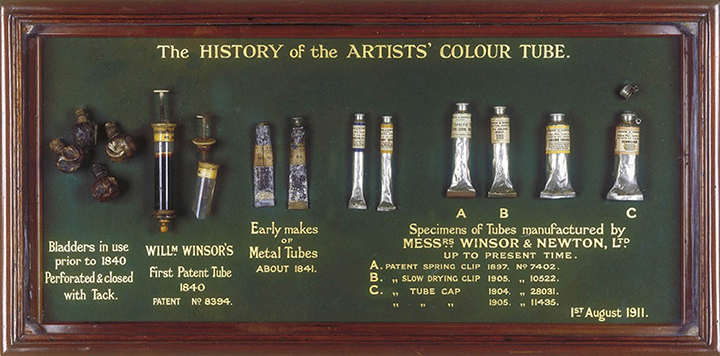

Pig bladders used before the invention of the collapsible paint tube. Cape Ann Cosmos.

If an artist wished to paint outdoors, the work began long before he ever reached the landscape. He had to mix his own paints by hand, grinding pigments and oil together on a stone slab until the paste was smooth and free of lumps. The process was time-consuming and the paint dried quickly, causing most painters to work with only a limited palette during each session.

Paint storage offered its own challenges. In those days, pigments were stored in a pig’s bladder and sealed with string. Using them meant puncturing the bladder with a pin and squeezing out paint. But it proved a messy ordeal. Once opened, the bladder could not be effectively resealed, and the paint lasted only a day or two before oxidizing. Artists adapted by working methodically, completing all passages of one color before advancing to the next.

Complicating matters further, the delicate bladders frequently burst open unexpectedly—hardly ideal companions for travel.

John Goffe Rand, Self-Portrait, c. 1836. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, USA. History Today

Like many artists, American portrait painter John Goffe Rand (1801–1873) struggled to keep his paints from drying up before he could use them to paint his canvases. Rand was born in 1801 in Bedford, New Hampshire to a family of farmers. As a young boy, he was expected to join the family business—but his heart was elsewhere. Drawn to art, he left for Boston, where he began as an apprentice cabinetmaker and later worked grinding pigments for paint. His passion soon led him to portrait painting. Though he lived and worked in both Boston and New York, it was during his time in London that he would leave his most lasting legacy.

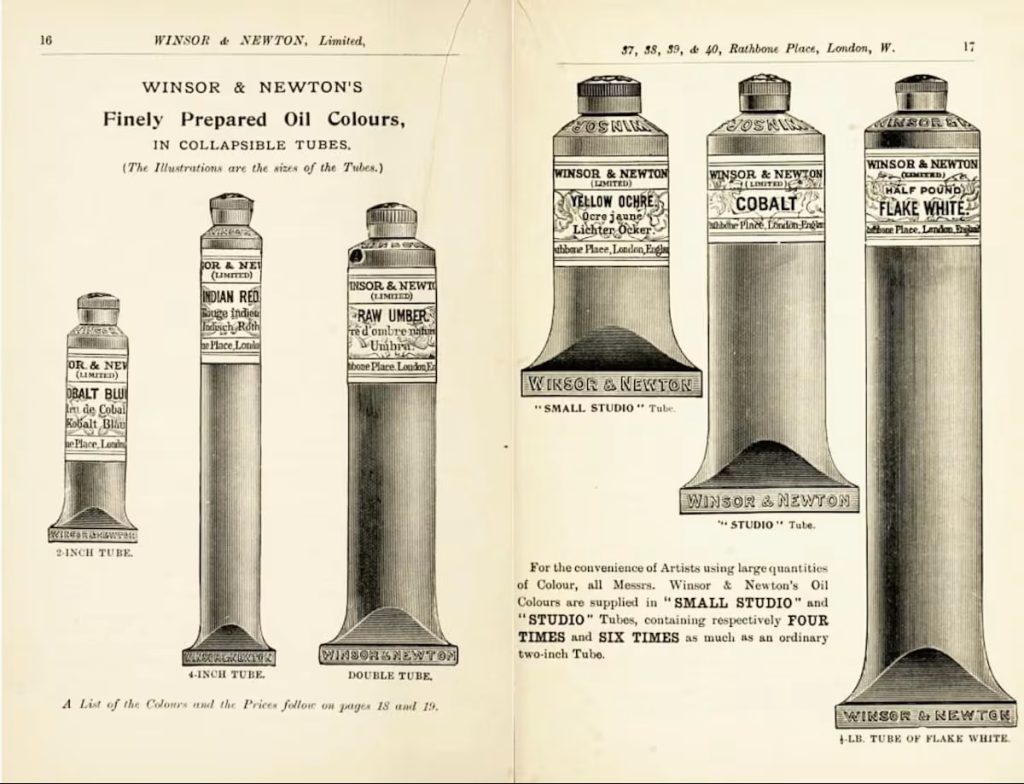

Winsor & Newton collapsible tubes. El País.

In 1841, Rand transformed painting forever when he patented a flexible tin tube for storing oil paint. Unlike the pig bladder, his tube didn’t leak, burst, or spoil the colors inside. It was sealed with a screw cap, could be opened repeatedly, and kept the paint fresh with an airtight seal.

But creating this invention posed numerous challenges: Rand had to find a material that wouldn’t react with the paint—a metal stable enough to keep its contents pure, yet soft enough to roll up without cracking. Tin proved the perfect solution: inert, malleable, and durable.

His patent, Improvement of the Construction of Vessels or Apparatus for Preserving Paint, was issued by the United States Patent Office on September 11, 1841 as Patent no. 2,252.

For the first time in history, artists could complete an oil painting on-site, en plein air—in the countryside, at the beach, or on the streets of Paris. They recorded the effects of natural light, painting one color atop the next, following Camille Pissarro’s advice: “Don’t paint bit by bit, but paint everything at once placing tones everywhere.”2

Until then, artists used a limited number of colors, which had remained nearly the same since the Renaissance. But thanks to Rand’s invention, artists began purchasing them from suppliers. New pigments were invented by French industrial chemists in the 19th century, such as chrome yellow and emerald green. In time, materials became more affordable and more accessible.

The tin tube. El País.

Even so, the shift came with its share of challenges. Painting outdoors took some getting used to. Claude Monet once ventured out to sea to paint an arched rock for his Waves at the Manneport (1885). The artist was so concentrated on his work that he was thrown against a cliff by rough waves and dragged into the sea along with his materials. His painting was destroyed.

In a letter to his companion, Alice Hoschedé, Monet wrote:

After another rainy morning I was glad to find the weather slightly improved: despite a high wind blowing and a rough sea, or rather because of it, I hoped for a fruitful session at the Manneport; however, an accident befell me. Don’t alarm yourself now, I am safe and sound since I’m writing to you, although you nearly had no news and I would never have seen you again. I was hard at work beneath the cliff, well sheltered from the wind, in the spot which you visited with me; convinced that the tide was drawing out I took no notice of the waves which came and fell a few feet away from me. In short, absorbed as I was, I didn’t see a huge wave coming; it threw me against the cliff and I was tossed about in its wake along with all my materials!

My immediate thought was that I was done for, as the water dragged me down, but in the end I managed to clamber out on all fours, but Lord, what a state I was in! My boots, my thick stockings and my coat were soaked through; the palette which I had kept a grip on had been knocked over my face and my beard was covered in blue, yellow etc.

Letter to Alice Hoschedé, November 27, 1885. Seattle Art Museum.

Claude Monet, Waves at the Manneport, ca. 1885, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC, USA.

The invention of the paint tube kickstarted an unexpected revolution. In the words of Renoir:

Without paints in tubes, there would have been no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro…no Impressionism.

Jean Renoir, Renoir: My Father, Mercury House, 1988, p. 734.

By freeing artists from the confines of the studio, it transformed not only how paintings were made, but the site and intent of artistic production. This newfound mobility allowed artists to work directly from life to capture fleeting light, movement, and atmosphere with unprecedented immediacy. In doing so, the paint tube did more than alter technique—it helped announce the dawn of modern art, reshaping artistic practice and changing the landscape of painting forever.

The History of the Artists’ Colour Tube & The Manufacture of Collapsible Metal Tubes for Artists Colours, c. 1911. Winsor & Newton.

If you want to learn more about the Impressionist movement, check out our French Impressionism Online Course! It will help you deepen your understanding of Impressionism.

Renoir to Durand-Ruel, Letter from 1882 in: Lionello Venturi, Les Archives de l’Impressionsme, 1939. vol I. p. 115.

Perry Hurt, “Never Underestimate the Power of a Paint Tube”, Smithsonian Magazine, 2013. Accessed: Dec. 18, 2025.

Perry Hurt, “Never Underestimate the Power of a Paint Tube”, Smithsonian Magazine. May 2013. Accessed: Dec. 18, 2025.

Mathew Lyons, “John Goffe Rand Invents Paint Tubes”, History Today. Vol. 73. Issue 9. September 2023. Accessed: Dec. 18, 2025.

Chris Munkholm, The Invention Path to Plein Air and Impressionism. Cape Ann Cosmos. September 26, 2022. Accessed: Dec. 18, 2025.

Michael Rosenthal, Thomas Gainsborough, Oxford University Press 2003.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!