From Victim to Temptress: Salome in Art

For centuries, artists interpreted the biblical story of Salome and turned it into a lasting theme in art. But where did this fascination come from?...

Edoardo Cesarino 22 January 2026

Olga Boznańska was one of the greatest Polish painters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, known mostly for portraits with muted, elegant colors. These portraits reveal the human soul, often filled with sadness and deep gazes. Here are 10 artworks show the personal technique that Boznańska developed over the years, shaped by her personal experiences but also inspiration from various artists and a life spent between different cities.

My paintings look magnificent because they are true. After all, they are honest, noble, and devoid of pettiness, affectation, and deceit. They are silent and vivid, as though separated from the viewers, but with a gauzy curtain. They have their own atmosphere. I showed 30 paintings; I could have shown double that if there had been enough room.

Olga Boznańska’s letter to Julia Gradomska, 1909, trans. by the author.

Olga Boznańska, Self-Portrait, 1906, National Museum in Kraków, Kraków, Poland. Museum’s website.

Olga Boznańska (1865–1940), born in Kraków, Poland, was one of the greatest Polish painters. Although she worked during the Impressionist era, Boznańska never fully identified with the movement. Impressionists usually avoided black but used light, delicate tones and often painted outdoor scenes.

Boznańska used darker shades to express emotions and inner states in her own way. Her paintings are rich in feeling, characterized by elegant tones that create a delicate haze. All of this is perfectly captured in Self-Portrait. She mostly painted portraits, including many self-portraits, and occasionally elements of the natural world and interiors.

Her interest in painting was obvious from a young age. Her father was an engineer and supported her artistic pursuits financially, while her French mother, a drawing teacher, encouraged her creatively. The year 1881 marked a turning point: during a trip to Vienna with her parents, she saw the baroque works of Diego Velázquez and decided she wanted to become an artist.

Olga Boznańska, From a Walk, 1889, National Museum in Kraków, Kraków, Poland. Museum’s website.

In 1885, Boznańska moved to Munich, Germany. At the time, women had limited access to art schools there, so she continued her studies with private teachers. The Bavarian capital became the place where she truly learned how to paint. She quickly outgrew her teachers and drew inspiration from the world around her, spending much of her time at the Alte Pinakothek studying masterpieces by Vermeer, Rembrandt, and van Dyck.

Throughout her life, Boznańska often returned to Poland to exhibit her work. From a Walk was the first piece she showed to Polish audiences. It depicts a woman in a long white dress, holding an umbrella decorated with daisies. The woman’s pale skin blends with the muted, gray-blue background, creating a calm mood. This style, with soft tones, was not really appreciated by critics, who did not pay much attention to its innovative style, using a palette of whites and grays inspired by Whistler.

Olga Boznańska, Study of a Woman with a Girl, 1893, National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland. Museum’s website.

Study of a Woman with a Girl is one of Boznańska’s melancholic paintings. The figures appear thoughtful, with eyes that make them appear slightly distant, creating a nostalgic atmosphere. The young girl sits on the woman’s lap, and both look straight at the viewer with big, dark eyes.

Boznańska admitted that she was naturally a sad person, so her paintings are also filled with sadness and melancholy. This sensitivity is evident in the way she portrayed others. The eyes she paints are often deep and expressive. Sometimes the gaze looks a little blurry, but no matter how she depicts them, they always feel like a window into the person’s soul.

Olga Boznańska, Japanese Woman, 1889, National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland. Museum’s website.

The artist was also interested in Japanese art from an early stage of her career. At the end of the 19th century, this subject became popular in Europe and influenced many artists, including Olga. Boznańska created some works using this style. One example is a Japanese Woman, where a young female wears a light garment and holds a red Japanese fan that matches her lips, contrasting with the white dress. The woman has dark hair and eyes and stands slightly sideways, looking into the distance. Boznańska’s interest in Japanese art is also evident in her occasional choice of Japanese-inspired clothing.

Olga Boznańska, Portrait of Paul Nauen, 1893, National Museum in Kraków, Kraków, Poland. Museum’s website.

During her time in Munich, Boznańska painted a portrait of Paul Nauen, a German painter and teacher. The painting depicts him seated sideways on a sofa, dressed in black, with an elegant cup placed on the table in front of him. At first glance, he appears calm, posed with understated elegance. Yet some critics thought he looked weak, tired, or uninterested, because Boznańska portrayed him naturally, without trying to idealize him. This piece drew a lot of attention at the time. In this case, the criticism proved beneficial for Boznańska, showing her honesty and skill.

She consistently emphasized that she painted what she saw.

Type or race embodies character, and that is true beauty. It contains a soul that thinks, works, suffers, is weary, or tormented. None of these features should be changed. Besides, I cannot improve on nature—I paint what I see.

National Museum in Poznań, trans. by the author.

Olga Boznańska, Interior of the Parisian Studio, 1908, National Museum in Kraków, Kraków, Poland. Museum’s website.

Eventually, Olga Boznańska left Munich for the heart of the art world. In 1898, she moved to Paris, then the center of European art, where Impressionism was flourishing. Her long-held dream of living in Paris had finally come true—a city that, before her studies, had seemed too distant and not very suitable for a young woman, according to her father.

Another painting of Olga Boznańska, Interior of the Parisian Studio, depicts the space she rented, modest and simple, with a chair that looks quite luxurious because of its colors, placed in front of the sofa. The interior is kept in dark tones, with walls covered in numerous portraits. The room was a creative chaos, with cups of brushes often stained with paint and a sofa on which models spent long hours. Boznańska was known for painting slowly and meticulously, which meant her models often had to sit for extended periods.

Olga Boznańska, Portrait de Jeune Dame, 1903, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Museum’s website.

Olga Boznańska quickly adapted to life in Paris. Fluent in French from childhood, thanks to her French mother, she was able to move easily within the city’s artistic and social circles. Over time, she gained increasing recognition, and in 1912, she represented France at an exhibition in Pittsburgh with well-known painters: Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir.

Some of Olga Boznańska’s paintings are now on display at the Musée d’Orsay, including Portrait de Jeune Dame. Here, the artist once again demonstrates her refined taste in color. The woman in this artwork wears a dress in subtle green tones that match the color of her eyes, with a floral brooch adding a touch of elegance. Brown details of the furniture in the background make the scene very refined. All of this creates a scene in which the woman seems to blend naturally into the room.

Olga Boznańska, Girl with Chrysanthemums, 1894, National Museum in Kraków, Kraków, Poland. Museum’s website.

Girl with Chrysanthemums is Boznańska’s most recognizable work. Although painted in Munich, it gained wider recognition after the artist moved to Paris, where she exhibited her work at salons. The painting depicts a young girl standing against a gray background, wearing a very simple gray dress, and holding a bouquet of chrysanthemums. Her pale face and large eyes immediately draw attention. At first glance, her gaze appears almost uniformly dark, but the artist constructed it from several tones.

The longer one looks into such deep eyes, the more emotions can be read from the figure. The simple gray background, with touches of brownish tones in the corners, enhances this effect. Interestingly, the girl is the same model Boznańska had painted earlier in Study of a Woman with a Girl.

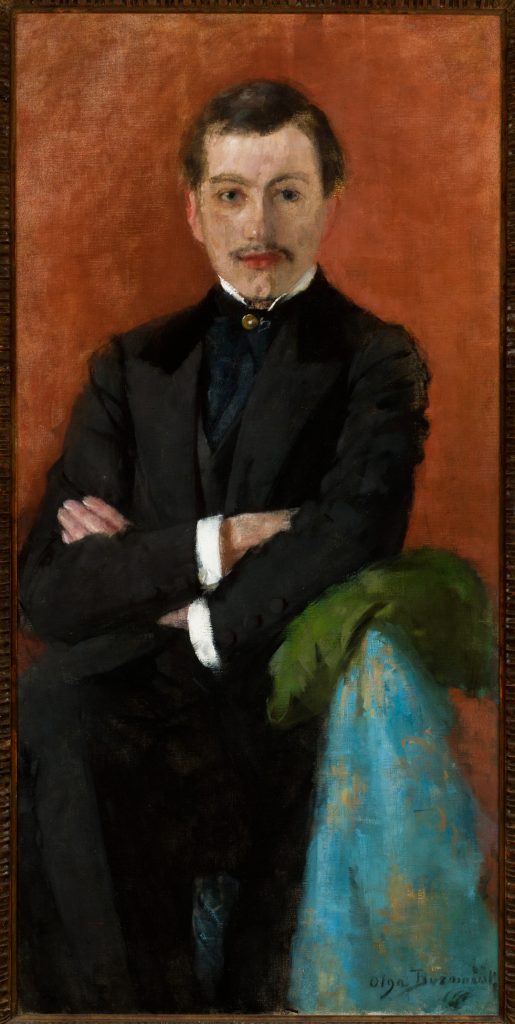

Olga Boznańska, Portrait of Józef Czajkowski, 1892, National Museum in Kraków, Kraków, Poland. Museum’s website.

While living in Paris, Olga Boznańska was engaged to Józef Czajkowski, a Polish architect and painter. They first met in Munich around 1891–1892, when Czajkowski went there to study art. During that period, she painted Portrait of Józef Czajkowski, depicting him in an elegant pose, dressed in a suit with his hands folded. He looks confident, both through his appearance and the look in his eyes. The background is a deep orange, which adds warmth to the painting, possibly suggesting the beginning of a connection between the two.

After completing his studies, Czajkowski returned to Kraków, while she moved to Paris. Despite encouragement from Czajkowski and from Boznańska’s father to return to Kraków, she remained determined to stay in Paris and focus on her career. Their long-distance relationship, combined with her strong sense of independence, eventually led Czajkowski to end the engagement. She consistently emphasized that she wanted to be seen first as a person, and only secondarily as a woman. Painting was more important to Olga Boznańska at that time.

Olga Boznańska, Poppies, after 1920, National Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland. Museum’s website.

Boznańska also painted flowers and still lifes. Poppies, created after 1920, depicts a simple bouquet arranged slightly unevenly in a vase. It is kept in darker shades, with soft edges and visible brushstrokes. The bouquet features red and white flowers against a rich brown background with touches of green. Additionally, Poppies also carry rich symbolic meaning. Perhaps the artist chose poppies to evoke ideas of memory and the fleeting nature of life. In her later years, she faced health problems, but that did not stop her from doing what she loved most–painting.

Whether it was portraits, flowers, or interiors, she continued to bring feeling to all her work.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!