Masterpiece Story: The Cardsharps by Caravaggio

The Cardsharps is an early masterpiece of Baroque art by Caravaggio that explores the revolutionary theme of crooked card playing. Let’s delve...

James W Singer 11 January 2026

Few artworks are as heavy in meaning and societal investigation as Ford Madox Brown’s Work. This is a unique masterpiece which manages to depict Victorian society and its deep-rooted issues with a keen critical eye—if a little unsubtly. Here is the story of this fascinating snapshot of life in Victorian England.

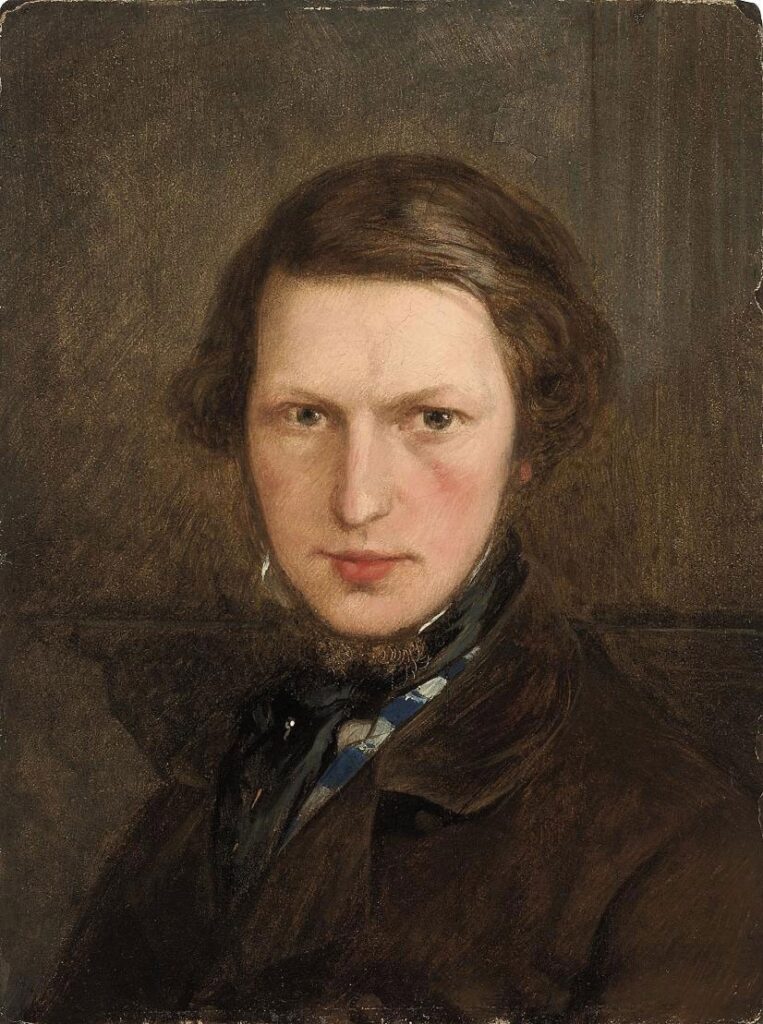

Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) was a Pre-Raphaelite painter by style who dedicated most of his life and art to portraying the societal issues afflicting England in his time. His artworks were often created with the purpose of generating a debate on momentous topics, such as his iconic The Last of England, which spoke to issues of immigration in the period. Brown’s critical (often satirical) takes on what he felt were increasingly shallow societal values have led to him being referred to as a Victorian William Hogarth (1697–1764)—the renowned 18th-century British painter best known for his “moral works.”

Ford Madox Brown, Self-Portrait in a Brown Coat, c. 1844, private collection.

Work is Brown’s most recognizable piece. Depicting a scene in the London suburb of Hampstead, it’s Brown’s attempt to capture a snapshot of Victorian society and its fundamental problems. It is, at its core, thought-provoking and educational, more than it is meant to be aesthetically pleasing or stylistically accomplished. Brown deliberately uses forthright symbolism to convey his message, leaving little room for subtle interpretation. The first and main version of this painting, housed in Manchester, was completed in 1865. It took Brown 13 years. There is also a second, smaller commission, completed earlier in 1863 and housed in Birmingham.

Ford Madox Brown, Work, 1852–1865, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK.

In the mid-1800s, a seismic shift was happening in British society. The Industrial Revolution, which had started in Britain in the late 18th century, was now in full swing. Amongst other impacts, it led to a boom in urban life and factory jobs. This irreversibly changed life for most Britons, and agriculture and farming were now confined to the margins.

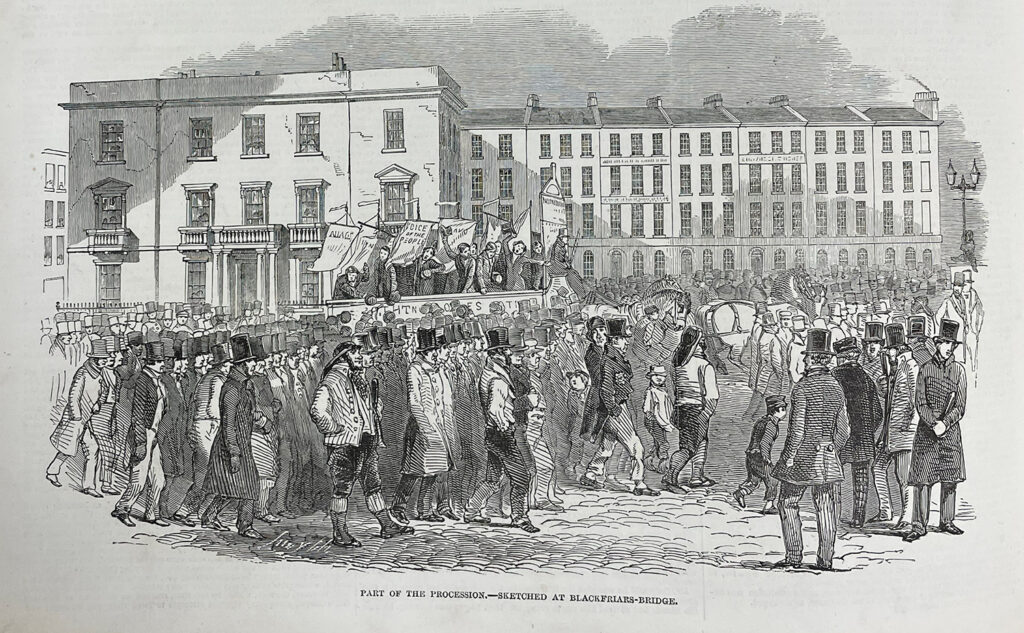

A Chartist meeting at Blackfriars Bridge, The Illustrated London News, April 15, 1848.

In turn, this contributed to the rise of the working class—an increasingly large section of society, which was now sharing the cities with the middle and upper classes. With time, the working class became more aware of their importance and sheer numbers. They began to protest against a political and class-based system that still dismissed them and demanded rights and recognition, such as the right to vote.

Ford Madox Brown, Work, 1852–1865, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK. Detail.

Brown was a fervent supporter of the new working class. His beliefs took inspiration from Thomas Carlyle, a prominent philosopher who theorized the superior moral value of honest physical labour. Carlyle even features in Brown’s masterpiece as one of the two men standing to the far right of the scene (the other is theologian F. D. Maurice, creator of the so-called Christian Socialism movement).

As the title suggests, the central theme of the painting is that of work—or rather, the moral and societal importance of “real” work.

Ford Madox Brown, Work, 1852–1865, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK. Detail.

The painting revolves around the man in the centre-left. He is part of a group of “navvies”—a term that defines manual laborers involved in civic projects, often building canals. Here, they are working on a sewer. Brown uses this man to present a very idealized version of a section of the working class. He is majestic and statuesque in an almost Greco-Roman fashion. Strong and muscular, he stands proud in the centre of the composition, bathed in light. He is even holding a rose between his teeth. He is unquestionably the hero.

To the left are other members of Victorian society, specifically people who have never been taught the value of work. There is a woman distributing religious leaflets and another holding a parasol—examples of the Victorian middle class. The latter, modeled on Brown’s wife Emma, is there to warn against the fleeting nature of beauty (as opposed to the long-lasting impact of honest manual work). At the front, there is a man selling weeds and flowers. His ragged clothes and cagey demeanour put him in stark contrast with the monumental navvy. Though they are from a similar social class, they are nothing like each other.

Ford Madox Brown, Work, 1852–1865, Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK. Detail.

Behind the navvies are two members of the upper class, depicted on horseback, who have never needed to work because of their status. They are at the top of the pyramid, physically and figuratively above the laborers. However, crucially, they are in the shadows, as if being surpassed in importance. To the right of the navvies are other workers, whose trades may be perceived as less valuable. Amongst them, underneath the balustrade, are agricultural workers left behind by the new industrialized society.

Finally, at the very bottom of the painting, is a group of children. The ragged oversized clothes (as well as the black ribbon over the shoulder of the baby) suggest they are orphans. In his catalog entry, Brown explains that the older child—depicted with her back to the viewer—is forced to act as a mother to the others.

Ford Madox Brown, Work, 1852–1865 Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester, UK. Detail.

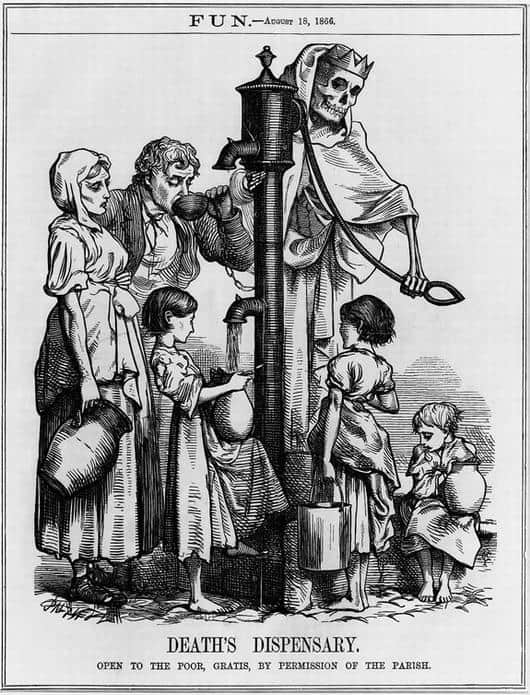

Street children were a significant issue in Victorian England and one that Brown was particularly concerned about. Many were left orphaned because their parents had succumbed to diseases, including cholera. A mixture of overpopulation, poor sanitation, and degrading living standards had caused cholera to sweep through the population, causing deaths and irreparable damage, particularly to the lower classes. The navvy Brown portrayed so idealistically, is working on improving this epidemic through the provision of new water supplies.

George John Pinwell, “Death Dispensary” in: Fun, August 18, 1866. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

However, though Brown depicts some of the workers as heroic, others are much less so, such as the beer seller and the other navvy, who is drinking. Alongside cholera, Brown wanted to highlight what he considered the plague of excessive beer drinking. He considers this to be the cause of immoral and criminal behavior, particularly in the lower classes. As a result, innocent children were left orphaned and living on the streets. Brown uses them in his painting to denounce who the true losers are in a society he perceived was increasingly lacking in moral values.

Gerald Curtis: “Ford Madox Brown’s Work: An Iconographic Analysis”, The Art Bulletin, Dec. 1992 74(4), pp. 623–636.

Rebecca Jeffrey Easby: Ford Madox Brown, Work. Accessed Jul. 27, 2025.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!