Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

Self-Portrait by Marie-Denise Villers showcases the genius of a leading female artist of Napoleonic France.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802,The Louvre, Paris, France.

Marie-Denise Villers (1774-1821) was a Parisian female artist who specialized in female portraits during the Neoclassical era of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Her life and career, therefore, spanned the infamous French Revolution of 1789 and the glorious First French Empire. Villers began to paint in 1799, under the tutelage of the era’s preeminent painters such as Jacques-Louis David. The same year, she displayed her first major work in the Paris Salon. She married Michel-Jean-Maximilien Villers and continued her painting career with his encouragement to become a rare career woman in the art world of Napoleonic France.

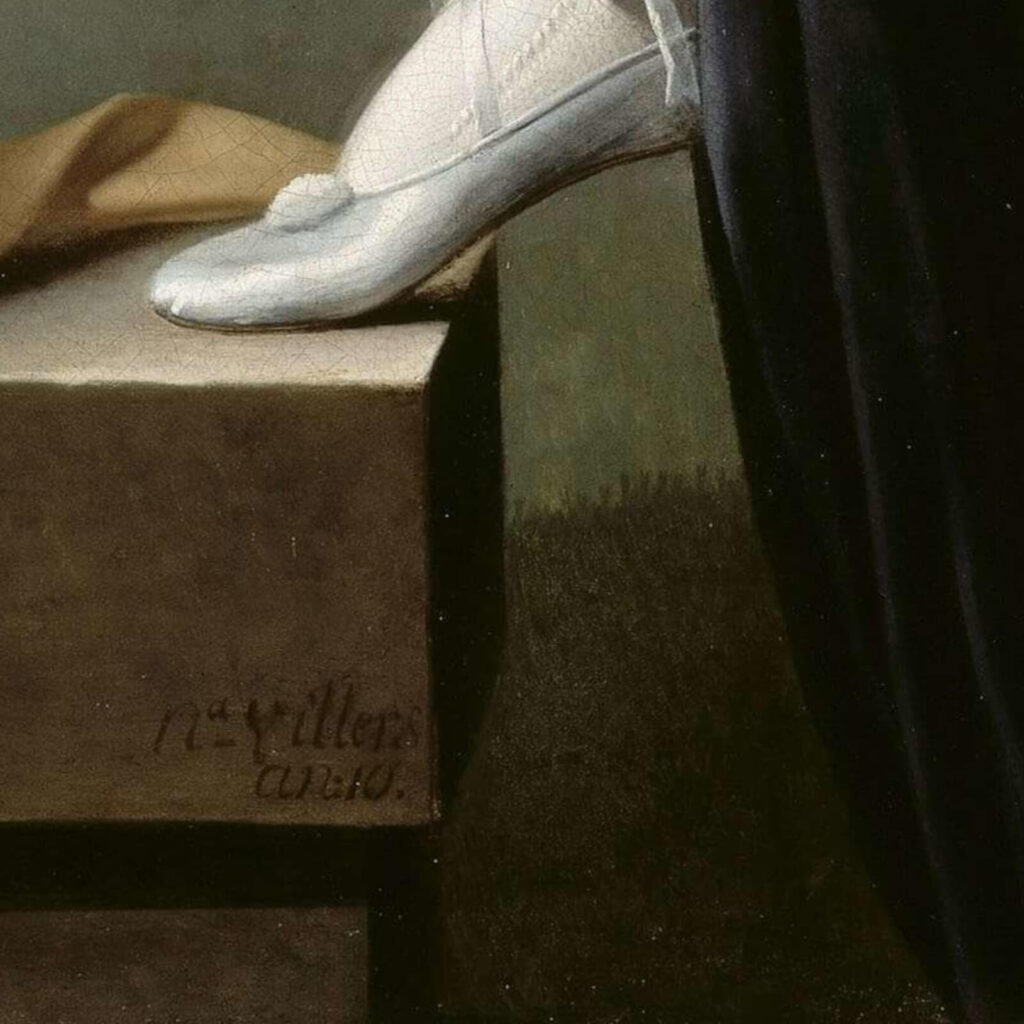

Self-Portrait, first displayed at the Paris Salon of 1802, is a highlight in Marie-Denise Villers’ career. It demonstrates her technical flair with beautiful rendering of skin and fabrics that lead to the vast appreciation of her portrait paintings. The painting is often presented as the Portrait of Madame Soustra however, Louvre’s latest findings confirm it is in fact a self-portrait.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

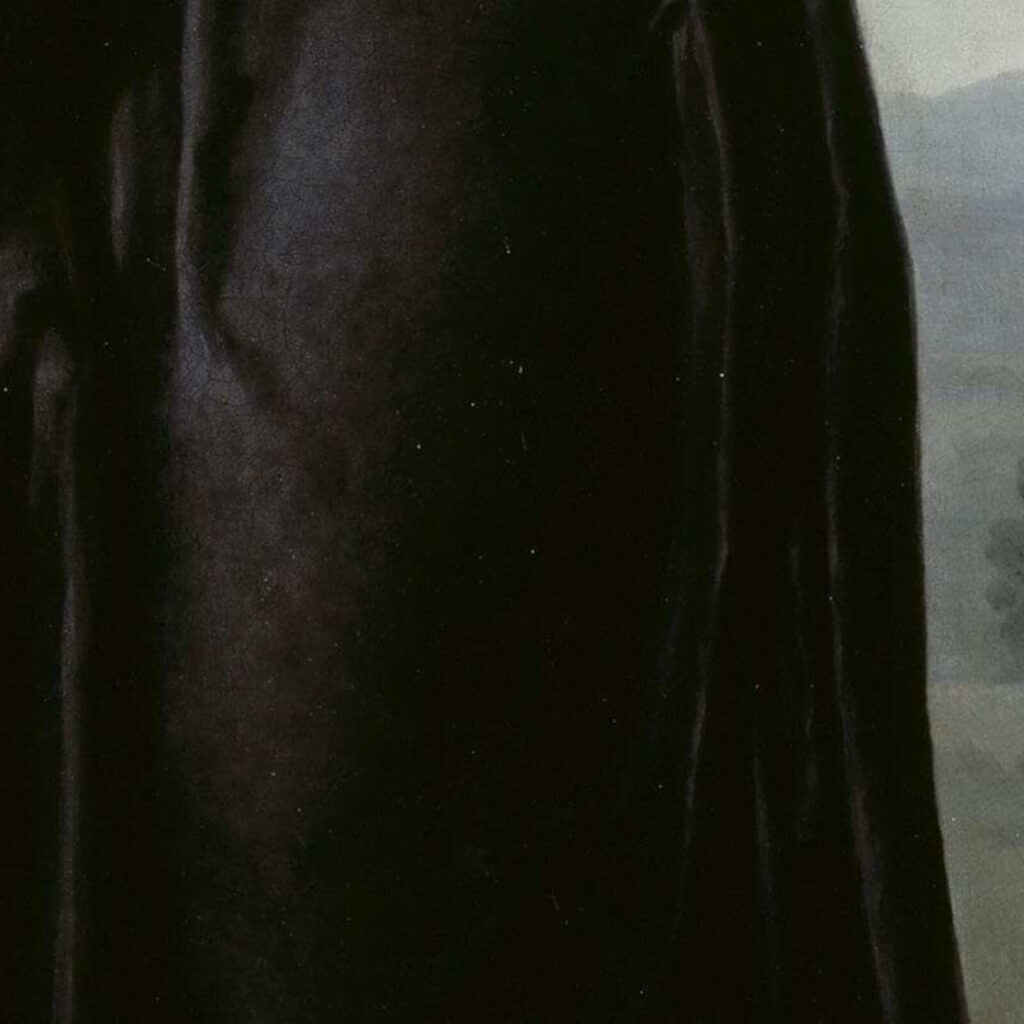

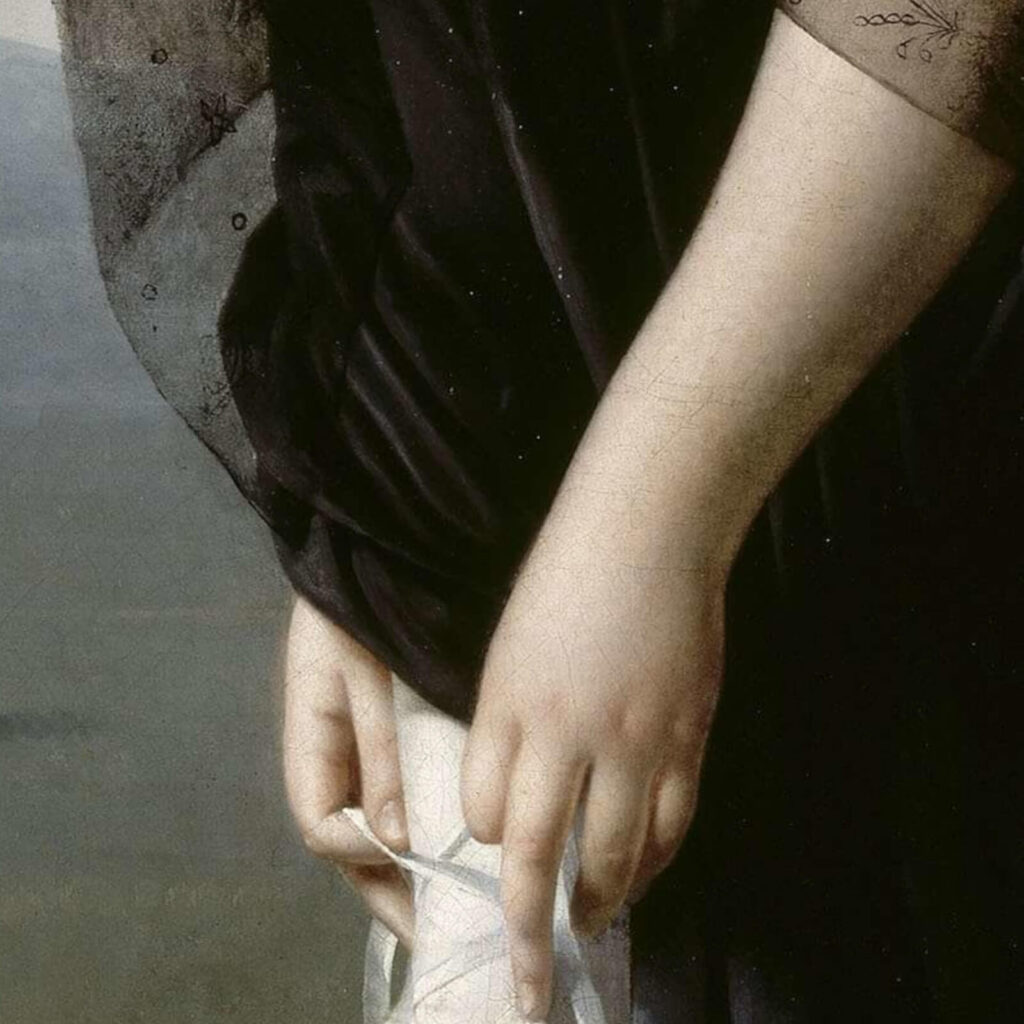

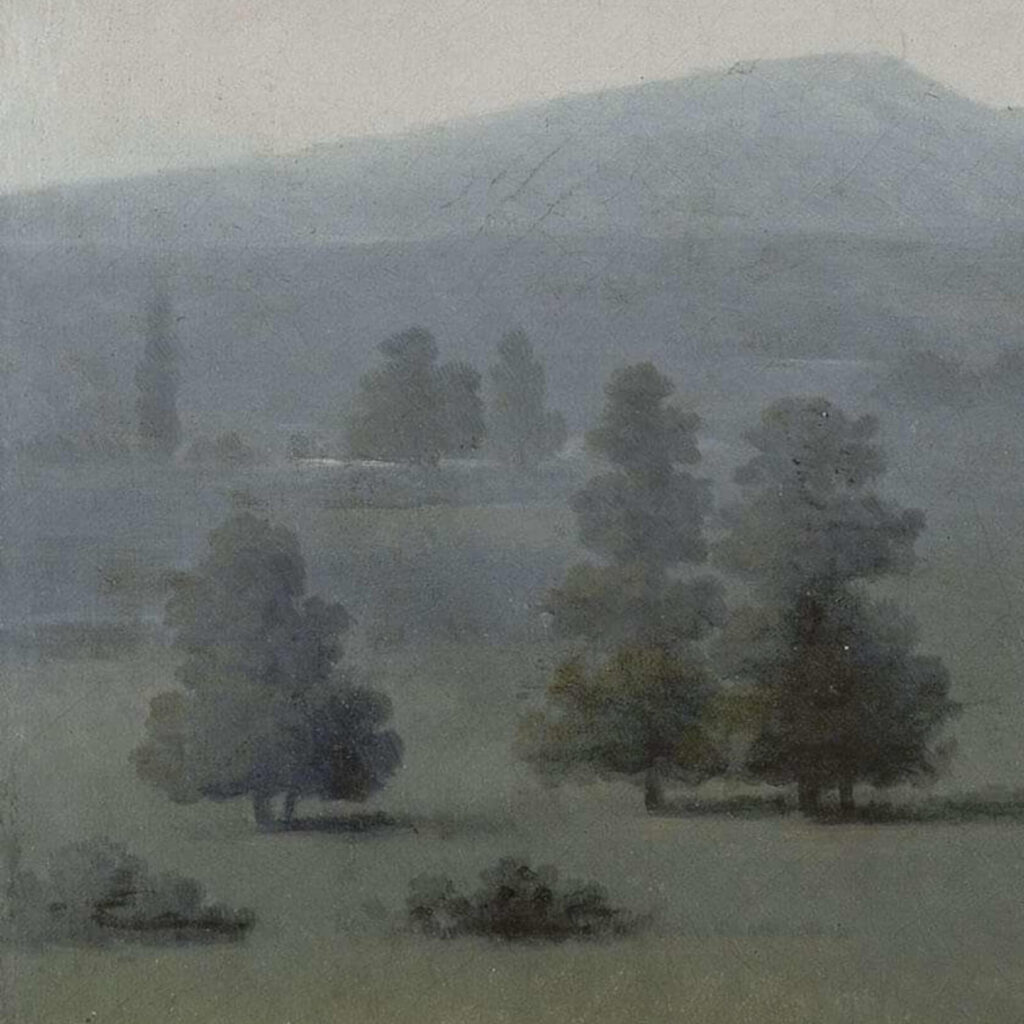

Self-Portrait is an oil on canvas measuring 1.46 m (4 ft 9 in) high and 1.14 m (3 ft 9 in) wide. It presents a 28-year-old Marie-Denise Villers leaning on a bench to tie her shoe after a walk in the countryside. With her gold-colored gloves already sitting on the bench alongside a single pink rose, she crouches over the shoe in a black silk skirt, a red silk bodice, a white cotton chemise, and a black lace shawl. Her clothes form cascading waves of wrinkles that imply her body beneath, reflecting the sunlight. The lace shawl forms wispy layers that frame her delicate face. The image blends the mastery of a beautiful portrait with the mystery of a genre painting.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

Jacques-Louis David and other artists of the time commented on how realistic the portraits created by Marie-Denise Villers were compared to the sitters. Consequently, the face of Self-Portrait is naturally assumed to be a very accurate likeness. In addition to being a talented artist, Villers had porcelain skin, blonde hair, large eyes, and small red lips. She definitely fit within the traditional standards of female attractiveness in early 19th-century Europe.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

Marie-Denise Villers depicts her face shrouded in a flowing lace shawl. As it gathers on the left, it forms layers of transparency, translucence, and opaque. The darkest areas show many layers of lace blocking the viewer’s gaze, while the lightest areas imply a single layer tinting the viewer’s perspective. The lace shawl is a great study of sheer fabric, varying layers, and filtered light.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

Marie-Denise Villers did not use her own hands for her Self-Portrait. She used the hands of a model, Marie-Louise Soustras. Perhaps Villers felt that Soustras had a more appealing set of hands to capture? Regardless, Villers blends the hands of Soustras seamlessly into the portrait. An uninformed viewer would never know. However, because of this use of the model’s hands, the portrait inadvertently was mistitled Portrait of Madame Soustras for over a century due to a letter stating that Madame Soustras posed for it. She did, but just for the hands! Rarely has a hand model caused so much confusion.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

A pair of gold silk gloves and a single fresh pink rose lay on the brown wooden bench at the foot of Marie-Denise Villers. The painting implies that Villiers was walking in the countryside and picked that rose along her way. She could have noticed or felt her loose right shoe and stopped to retie her shoelaces after placing the rose that on the bench. Then she removed her full-length gloves. She lift her right foot onto the bench and began to tie her laces.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

The viewer has just caught her in an indelicate moment as her ankle is revealed and her hands are exposed. There is a certain 19th-century risqué sensuality to this captured moment. However, Villiers does not look shocked or appalled but instead steadily looks at the viewer with an almost confrontational confidence. Villiers knows that she is doing nothing ethically wrong. She is just a woman tying her shoe after it became loose after a walk! And so she acts with calm and composure.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

Marie-Denise Villers captures a country walk, but where is she walking? Perhaps she is in Île-de-France, the region surrounding Paris, which was still very rural in the 19th century? However, such a sweeping vista is rare in Île-de-France. There always seems to be a road or a cottage somewhere because Île-de-France is the most populated of the 18 regions of France. Therefore, Villers may be portraying herself away from her native Parisian territory. Perhaps the viewer sees the landscape nearby a beloved vacation home? Many French, especially Parisians, have a vacation home deep in the country, frequently in the northwestern region of Normandy. Regardless, wherever Villers is walking, she is certainly not having a walk in Paris with the uninhabited landscape and distant mountain.

Marie-Denise Villers, Self-Portrait, 1802, The Louvre, Paris, France. Detail.

Prior to the 1990s, Villers was a fairly unknown female artist because many of her works were falsely attributed to her teacher and tutor, Jacques Louis David. If we look at it in a different light, this confirms the exceptional mastery that Villers displayed in her works. However, professional compliment aside, the misattribution led to Villers being almost a non-entity. She was a footnote in art history instead of an independent subject worthy of study.

Thankfully, the reputation of Marie-Denise Villers has been revised in the last 30 years. Several works, such as Self-Portrait and Portrait of Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, helped gain momentum in recognizing her achievements. It is easily said that there are probably several more masterpieces by Villers to be found and to be added to her legacy. Some are probably hanging in museums and houses, somewhere under the name David, School of David, or Unknown Artist.

Marie-Denise Villers certainly needs to be added to the greater narrative of Western European art. Eventually, perhaps 50 to 100 years from now, she will be spoken on equal terms as David, not because she was a great female artist, but because she was a great artist. Greatness cannot be hidden forever.

Marie-Denise Villers, Portrait of Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes, 1801, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Bauwens, Malika. “Marie-Denise Villers, Celle Qu’on a Prise Pour David.” Beaux Art Magazine. Grand Format, 12 April 2023.

“Etude de femme d’après nature.” Collection. Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. Retrieved 22 February 2024

“Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes.” Collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

Quinn, Bridget, and Lisa Congdon. Broad Strokes: 15 Women Who Made Art and Made History. San Francisco, CA, USA: Chronicle Books, 2017.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!