William H. Johnson in 10 Artworks—From Post-Impressionism to Folk Art

William H. Johnson’s paintings show a breadth of styles ranging from realism to Post-Impressionism, and later a folk art aesthetic that would...

Theodore Carter 12 February 2026

20 October 2025 min Read

In the midst of the Jim Crow era, Marian Anderson’s undeniable voice rocketed her to stardom and made her the subject of several enduring works of art with connections to Washington, D.C. Artists helped build Anderson’s legacy through a mural on the wall of a federal government building, a commemoration of her life on a United States postage stamp, and portraits in the halls of the National Portrait Gallery. In life, she was a threat to laws upholding a racist hierarchy. Now, Anderson’s image endures as a symbol of achievement in the face of oppression.

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1897, Marian Anderson began singing at the local Baptist church at the age of six and earned the nickname “Baby Contralto” for her rare, low female voice. After high school, she performed primarily at historically Black colleges and churches, and later at larger venues in the South and Northeast. In 1925, she beat out 300 other singers in a competition sponsored by the New York Philharmonic and earned a chance to perform with the orchestra. Later, she held a concert at Carnegie Hall.

Photograph of Marian Anderson. The Kennedy Center.

However, as a Black artist performing for mostly Black audiences, her career stagnated. She traveled overseas for the first time in 1928, and over the course of several years, she performed throughout Europe and Latin America. Free from the codified racism of the United States, her career flourished.

Anderson returned to the United States with new renown and performed at the White House in 1935. A year later, Anderson gave a benefit concert for the historically Black Howard University in Washington, D.C. This annual concert grew in popularity so that by 1939, Howard sought out Constitution Hall as a concert venue. However, the space was owned and operated by the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), an all-white organization that refused to let Marian Anderson, or any other Black artist, perform.

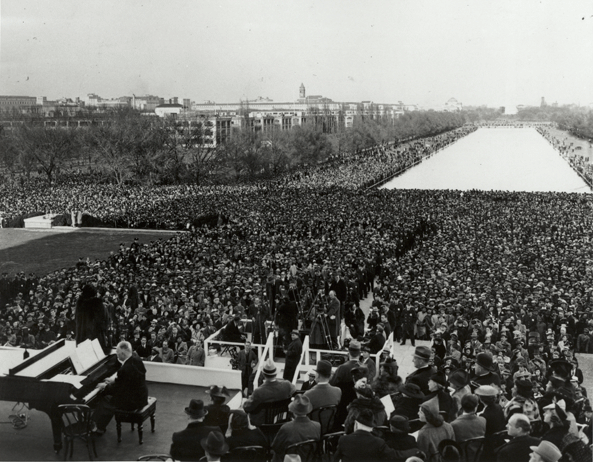

Marian Anderson’s Easter Sunday Lincoln Memorial concert, 1939. Hearst Metrotone News Collection, UCLA Film & Television Archive. YouTube.

After the DAR rebuffed Anderson and Howard University, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned as a DAR member and worked with the National Park Service to organize a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday, 1939, in front of an integrated crowd of 75,000. The concert became a hallmark of Anderson’s career. Years later, she returned to the Lincoln Memorial to perform during the 1963 March on Washington before Dr. King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

The two events forever linked Anderson with the Lincoln Memorial, and more broadly, Washington, D.C.

Mitchell Jamieson, An Incident in Contemporary American Life, 1940–1943, Stewart Lee Udall Department of the Interior Building, Washington, D.C., USA. dar.org.

Just weeks after Marian Anderson’s 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial, Edward Bruce, chief of the Section of Fine Arts of the Treasury Department, formed a committee to commemorate the event with a mural in the Department of the Interior building. After receiving proposals from 172 artists, the committee unanimously selected 25-year-old Mitchell Jamieson and paid him $1,700 to paint the approximately 4 x 2 m (157 15/32 x 78 3/4 in.) mural. The painting provides a unique perspective, focusing on the integrated crowd rather than the star singer.

Marian Anderson performing at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Much of the art Mitchell Jamieson produced in his long career came through federally funded programs, including post office murals, paintings for NASA, a stint as a World War II combat artist for the United States Navy, and as a civilian artist during the Vietnam War. Jamieson’s war experience haunted him, and in 1976, he died by suicide. The Washington Post’s Paul Richard wrote, “…ultimately, he could not and he would not stop remembering and drawing the horrors he had seen and those he had dreamed.”

Laura Wheeler Waring, Marian Anderson, 1944, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA.

Laura Wheeler Waring painted this commanding portrait, over six feet tall, for an exhibit entitled Portraits of Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin, which opened at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Several of the famous portrait sitters attended the opening, as did First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. The collection, featuring 22 portraits by both Waring, a Black woman, and white artist Betsy Graves Reyneau, then traveled the country. The Harmon Foundation sponsored the exhibit and sought to break down racial prejudice through portraiture. The collection is now owned by Washington, D.C.’s National Portrait Gallery.

Educated at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Waring, like Anderson and many other Black American artists of the era, blossomed during a trip to Europe. Upon returning to the United States, she became a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Betsy Graves Reyneau, Marian Anderson, 1955, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA.

The Harmon Foundation continued to fund the expansion of the Outstanding Americans of Negro Origin collection, bringing it to 47 paintings. Betsy Graves Reyneau completed her own portrait of Anderson in 1955. This painting features Anderson in a fur coat like the one she wore on the day of her Lincoln Memorial concert. The columns of the Lincoln Memorial are clearly visible in the background.

Born in 1888, Reyneau was a civil rights advocate as well as a painter. She became one of the first women arrested as part of the suffragist movement while picketing in 1917. Later, she moved to Germany, where she harbored Jews from Nazi soldiers. When she returned to the United States, Reyneau thought the Jim Crow laws were as abhorrent as the bigotry she’d seen in Europe, and through her painting, she worked to erode prejudice until she died in 1964.

William H. Johnson’s Marian Anderson #1 shows the singer during her 1939 Lincoln Memorial concert and was painted that same year. Johnson painted Marian Anderson again several years later, in 1945, as part of his 34-painting Fighters for Freedom series celebrating United States and international peacemakers. In this work, Johnson includes not only D.C. monuments but also iconic buildings and flags from around the world, representing Anderson’s worldwide fame. Anderson’s vocal coach, Kosti Vehanen, is seated at the piano.

In 1926, Johnson moved to Europe to further his career. In France, he studied modernism and married Danish artist Holcha Krake. By the time Johnson returned to the United States in 1938, he’d moved away from the impressionist style and into the flatter images and solid colors of a folk art style.

Albert Slark, Portrait of Marian Anderson on a stamp, 2005, National Postal Museum, Washington, D.C., USA.

In 2005, the United States Postal Service issued a Marian Anderson stamp, the 28th in their Black Heritage series. The painting is the work of Canadian artist Albert Slark, a portraitist who has painted several other stamps featuring prominent Americans.

Upon the release of the stamp, Marian Anderson’s family co-hosted an event with the DAR. In her remarks, DAR President General Presley Merritt Wagoner said of Marian Anderson: “The beauty of her voice, amplified by her courage and grace, brought attention to the eloquence of the many voices urging our nation to overcome prejudice and intolerance. It sparked change not only in America but also in the DAR. I stand before you today wishing that history could be rewritten, knowing that it cannot, and assuring you that DAR has learned from the past.”

Carla Scemama, Art for The Voice of Freedom, 2023. Photograph by Library of Congress via PBS.

Contemporary artist Carla Scemama created this work for the 2023 PBS documentary The Voice of Freedom, produced in the D.C. area. The documentary was part of their American Experience series, “bringing to life the incredible characters and epic stories that have shaped America’s past and present.” The series is currently on hold after the federal government stripped funding from PBS in 2025.

Scemama mostly paints female subjects and seeks “…to put all different kinds of women on the pedestal where they belong.” When asked about this painting specifically, Scemama stated, “My intent was to depict Marian Anderson in color while letting the background inform her character, particularly her historic performance at the Lincoln Memorial, which has become so closely tied to her legacy of resilience and dignity.”

Forever linked with Washington, D.C., and the Lincoln Memorial, Marian Anderson’s story resonates today as a significant turning point in the complex racial history of the United States. Portraits of Anderson—many of which were funded by the U.S. government and remain in D.C. on the walls of federal buildings, or hanging in Smithsonian museums—are reminders of her triumph in the face of injustice.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!