Ferdinand Hodler – The Painter Who Revolutionized Swiss Art

Ferdinand Hodler was one of the principal figures of 19th-century Swiss painting. Hodler worked in many styles during his life. Over the course of...

Louisa Mahoney 25 July 2024

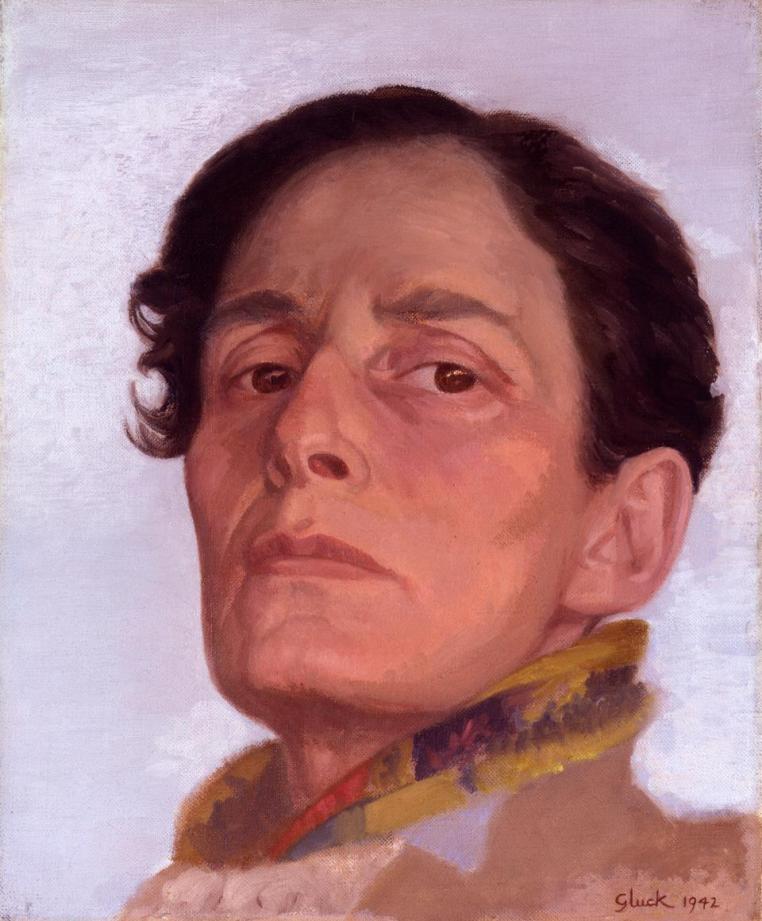

DailyArt Magazine wants to join in the promotion of tolerance and raise awareness of the prejudices faced by LGBTQ+ people. Therefore, we feature a queer Jewish British artist, Gluck, who chose to live the way Gluck wanted, not compromising on social conventions and gender norms. Gluck refused any forenames or prefixes and out of respect we will avoid using gendered pronouns when referring to the artist.

Gluck was born in 1895 as Hannah Gluckstein. The artist’s Jewish family owned the Lyons catering empire in London. Gluck’s parents weren’t in favor of Gluck pursuing an artistic career, but nevertheless, they trusted Gluck with a fund that allowed the young artist to make a life of their own.

Gluck attended St John’s Wood School of Art between 1913 and 1916 before moving to west Cornwall and joining the artists’ colony in Lamorna and purchasing a studio. However, Gluck didn’t want to be a part of any movement and always insisted on solo exhibitions.

To create Gluck, the young artist chose this name and began dressing androgynously in trousers and ties (Gluck even posed for Tatler Society Magazine at the beginning of their career). However, Gluck didn’t chase fame, mostly painting flowers and portraits. “No prefix, suffix, or quotes,” said the back of Gluck’s prints.

Cheska Hill-Wood, gallery manager of the Fine Art Society, with which Gluck was connected, said:

It wasn’t that she didn’t want to be a woman, and it wasn’t that she wanted to be a man. She just wanted to be Gluck.

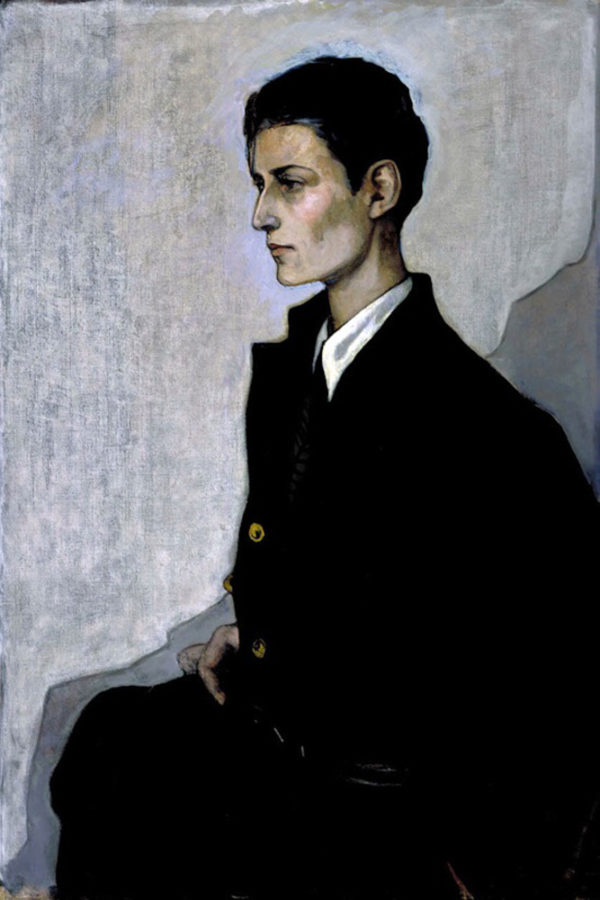

In 1923, Gluck met an American artist Romaine Brooks and the two painted portraits of one another. Brooks’s painting of Gluck, Peter (a Young English Girl) was very controversial because of the blatant androgyny of the sitter. Yet, the most important person in Gluck’s life was Nesta Obermer, a socialite married to an American businessman. Nevertheless, Gluck and Obermer symbolically married on May 25, 1936. Medallion celebrates the couple’s outing to Fritz Busch’s production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni. As Gluck’s biographer wrote:

They sat in the third row, and she felt [that] the intensity of the music fused them into one person and matched their love.

Diana Souhami, Gluck: Her Biography.

It was the first public declaration of Gluck’s love and commitment. Gluck wrote to Obermer:

Now it is out, and to the rest of the Universe, I call Beware! Beware! We are not to be trifled with.

With time, Gluck became very possessive and demanding with Obermer, who broke off their relationship in 1944. Moreover, Obermer destroyed all evidence of their life together.

Gluck began a new relationship, as troubled as the one with Nesta Obermer, with Edith Shackleton Heald, the first female reporter in the House of Lords. Having moved into Healds’ house in Sussex, Gluck often argued with her and her sister Norma and furthermore retired from painting. However, in 1973 Gluck organized an exhibition of 52 works at the Fine Arts Society which was very successful with critics and buyers.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!