Salvatore Busuttil and the Grand Tour Souvenirs

Art and tourism have a long and complex relationship. At the peak of the Grand Tour in Rome in the 19th century, countless artists had made a living...

Justin Fenech 1 January 2026

19 February 2026 min Read

Akseli Gallen‑Kallela (1865–1931), one of Finland’s most famous painters, holds a distinctive place in European art at the turn of the 20th century. His career spans across styles and continents: from early Naturalism to Symbolism, from the Kalevala to East African landscapes, from Parisian studios to the desert of New Mexico. Over four decades, he kept rethinking his approach to painting, responding to political changes, personal experiences, and new landscapes. His works show the range of his artistic ambition, but also the threads that held his practice together—the search for a modern Finnish identity, the aesthetic demands of the fin de siècle, and the ongoing conversation between myth, memory, and lived experience.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Boy with a Crow, 1884, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland.

Painted when the artist was only 19 years old, Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Boy With a Crow marks a key moment in the emergence of Nordic Modernism. Clearly influenced by French Naturalism, the painting also hints at the Symbolist sensibility that would later define much of Gallen-Kallela’s work—an inwardness attuned less to the reality of the external world than to the boy’s inner, subjective world. The boy is presented without idealization or sentimentality, an autonomous subject rather than a moral or political emblem.

This approach reflects broader shifts in Scandinavian art during the 1880s, as artists exposed to Paris began challenging academic conventions. The painting’s simplicity, subdued colors, and ambiguous narrative helped establish a distinctly Nordic modernist language that emphasized nature, interiority, and national identity without overt Symbolism or Social Realism.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Démasquée, 1888, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland.

Démasquée is one of the best-known works from Gallen-Kallela’s Paris years (1884–1889). Depicting a nude woman who has just removed her mask, contemporary critics have likened it to Manet’s Olympia—the direct gaze, the studio props, the stillness. Yet, Gallen-Kallela complicates the scene with layers of cultural references: a vanitas-like skull half-hidden behind a lily, japoniste fans, and, more importantly, the Finnish ryijy rug on the sofa, whose intense red pattern echoes the painter’s own heritage and the Finnish cultural identity he would soon help define.

Démasquée thus becomes more than a genre scene: it is an early experiment in cultural translation, where the unmasked figure mirrors the artist’s own search for an authentic voice amid the competing artistic currents of the late 1880s.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Aino Myth, Triptych, 1891, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland.

After returning to Finland and marrying Mary Helena Slöör in 1890, the Aino Triptych marked the painter’s first engagement with the Kalevala (the Finnish epic) and stands as a foundational work in the formation of Finnish national art. The triptych follows the encounter between the aging sage Väinämöinen and the young maiden Aino, whom he hopes to marry. The initial meeting in the forest, Aino’s refusal and flight, and her final metamorphosis in the water use a pictorial language that moves beyond descriptive realism toward a more poetic, stylized mode of representation.

Gallen-Kallela was searching for a visual language that could translate Finnish myth into a modern idiom, and the Aino Triptych became his breakthrough. In this early synthesis of folklore, landscape, and psychological depth, Gallen-Kallela found the direction that would define his career and help shape the visual identity of the Young Finland movement.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, The Defense of the Sampo, 1896, Turku Art Museum, Turku, Finland.

Gallen-Kallela’s Defense of the Sampo marks a shift in the artist’s Kalevala imagery, moving toward a bold, graphic style that would become central to his mature work. The painting depicts the battle in which Väinämöinen and his companions struggle against the sorceress Louhi for possession of the Sampo, the mythical source of prosperity. Unlike the earlier, more naturalistic Forging of the Sampo (1893), this scene is articulated around strong diagonals, flattened forms, and a vivid color palette that heightens the drama of the confrontation.

This moment was a turning point at which Gallen-Kallela’s interest in decorative abstraction, woodcut-like contours, and Japanese prints merged into a new visual language. The painting transforms a mythic episode into a modern national allegory, asserting cultural resilience at a time when Finland remained under Russian rule.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Lemminkäinen’s Mother, 1897, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland.

Lemminkäinen’s Mother occupies a significant place in Gallen-Kallela’s Kalevala cycle, revealing how the artist fused national mythology with the stylistic experimentation characteristic of the fin de siècle. While rooted in the epic’s narrative—Lemminkäinen’s mother retrieving and reassembling her son’s body from the river of Tuonela in the hope of resurrection—Gallen-Kallela introduced stylized, non-naturalistic elements such as the black, mirror-like water and the narrow band of golden light from heaven, signaling his engagement with the broader Art Nouveau search for a “new style” suited to modernity.

At the same time, the mother’s sculptural hands and muscular arms still reflect his classical academic training, while the composition also echoes the European Pietà tradition, revisited through a Finnish lens. This work exemplifies the tension between international influences and the desire to articulate a national visual identity. Gallen-Kallela transformed a mythical episode into a meditation on maternal devotion and cultural resilience, offering a new interpretation of the Kalevala at a moment when Finland was questioning its destiny.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, sketch for Ilmarinen Ploughing the Field of Vipers, 1899, Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki, Finland.

Gallen-Kallela created Ilmarinen Ploughing the Field of Vipers for the 1900 Paris World Fair, where Finland—still under Russian rule—presented itself as a culturally distinct nation. The painting draws on one of the Kalevala’s most perilous episodes: the sorceress Louhi forces the heroic blacksmith Ilmarinen to plough a field alive with serpents. Gallen-Kallela transformed this ordeal into a stark, emblematic confrontation.

In some versions (such as this sketch), he deepened the political meaning by placing the Romanov crown on the head of one of the vipers (the white one)—turning the field of snakes into a subtle allegory of Russian imperial oppression. This small but unmistakable symbol transforms the mythic episode into a veiled commentary on Finland’s own struggle, fusing national epic, modernist stylization, and political resistance into a single, strong image.

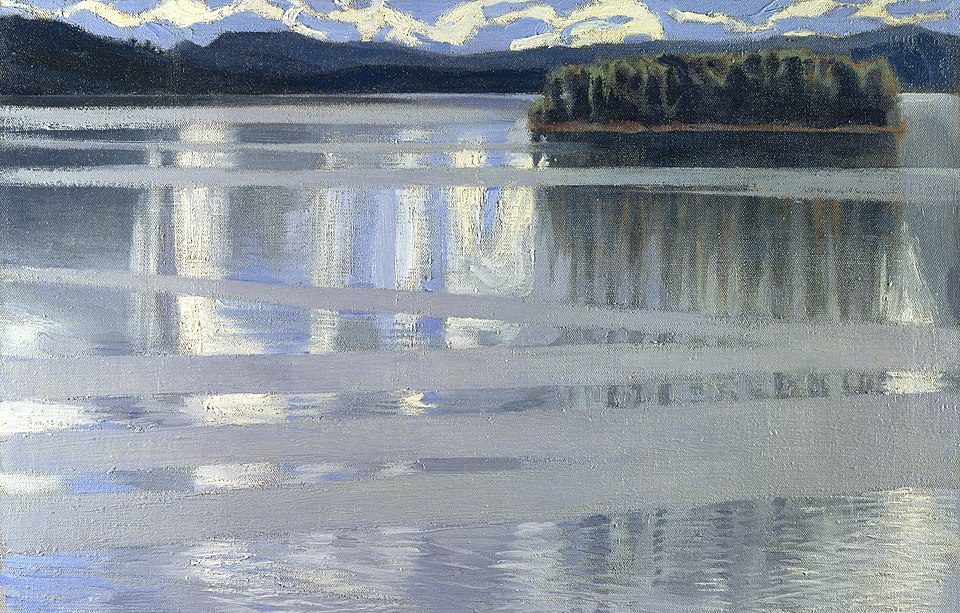

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Lake Keitele, 1905, National Gallery, London, UK.

Lake Keitele shows the artist’s shift from narrative illustration toward a simplified, modern landscape idiom. At first glance, the painting appears serene and naturalistic. Yet, its most striking feature—the silver diagonal bands that glide across the lake’s surface—reveals a deliberate stylization that moves far beyond observational realism. These bands, often interpreted as the wake of Väinämöinen’s magical boat in the Kalevala, transform the lake into a place where myth and nature converge.

Unlike the emotionally charged Lemminkäinen’s Mother, Lake Keitele abandons figuration altogether, allowing Gallen-Kallela to explore a more abstract, almost meditative language rooted in pattern, repetition, and the play of light. Gallen-Kallela produced several versions of the composition, suggesting that Lake Keitele became a site of experimentation where the artist tested the boundaries between representation and abstraction.

In 1907, in the midst of rising cultural nationalism and his own deepening commitment to Finnish identity, the painter officially changed his name from Axel Gallén—the Swedish form of his name which he used up to that point—to the more Finnish version, Akseli Gallen‑Kallela. He added Kallela after the name of his studio in the Finnish wilderness, which had become both a home and a symbol of his artistic mission.

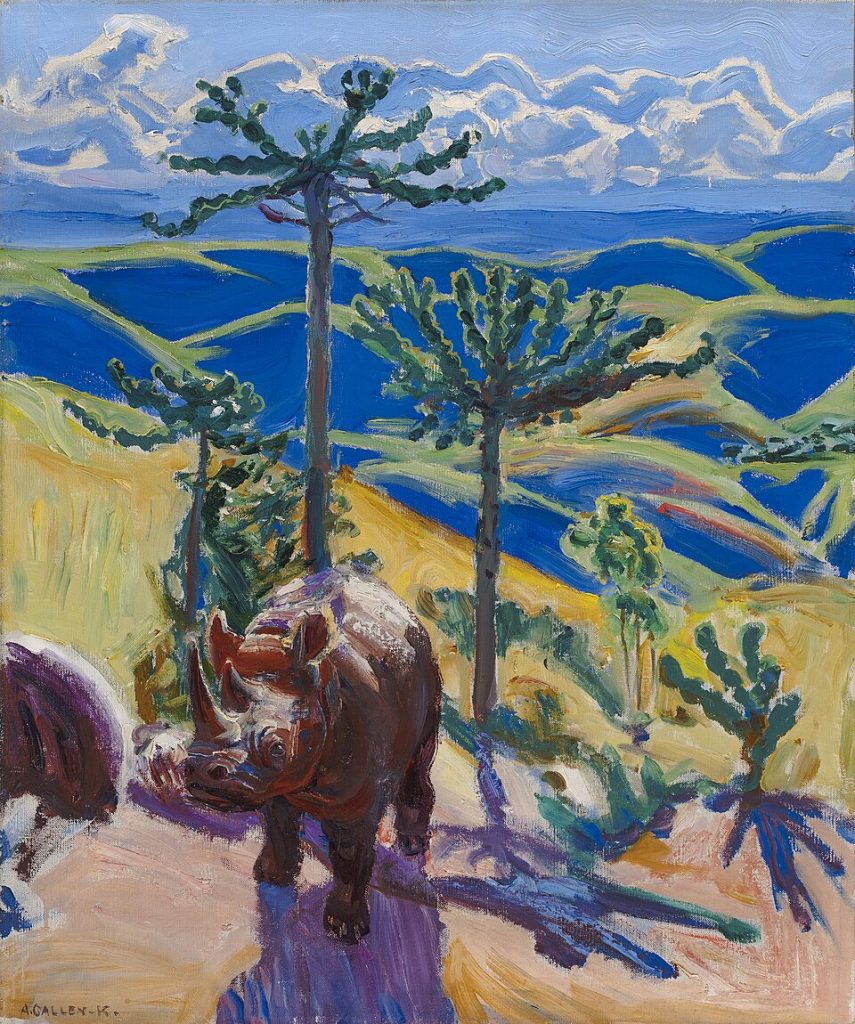

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Rhinoceros and Euphorbia Trees, 1909–1910, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

This name change marks the moment when the artist aligned his public identity with the cultural aspirations of Young Finland and with the Kalevala‑inspired project that defined his mature work. After first moving to Paris with his family in 1908, the Gallen-Kallelas settled in Nairobi, Kenya, for two years (1909–1911). During this time, the artist explored Expressionism and produced some of the most colorful works of his career, inspired by his new environment.

Rhinoceros and Euphorbia Trees belongs to the extraordinary body of work Gallen-Kallela produced during his East African journey, a period that marked a significant expansion of his visual vocabulary. The work captures a rhinoceros moving through a colorful landscape punctuated by the sculptural silhouettes of euphorbia trees—forms that fascinated Gallen-Kallela for their unusual geometry and imposing presence. Unlike the mythical intensity of his Kalevala subjects, this painting reflects a new, observational mode: the broad, freer brushwork and the heightened color palette reveal his encounter with African light and landscape, as well as his growing interest in Expressionist color and form.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Kirsti Playing the Cello, 1917, private collection. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Kirsti Playing the Cello is one of Gallen-Kallela’s most intimate and contemplative portraits, painted at a moment of profound political and personal transition. Created on the eve of Finland’s independence, the work turns away from the heroic nationalism of his Kalevala imagery. Instead, it focuses on the quiet concentration of his daughter absorbed in music.

The interior is warm and quiet, its soft palette and gentle light emphasizing the scene’s stillness, while the simplified forms reflect the more restrained yet modern naturalism that characterized his post‑African years. The cello becomes a stabilizing axis, suggesting the grounding role of home and culture at a time when the world outside was marked by war and uncertainty. In this gentle, introspective image, Gallen‑Kallela reveals a private side of his artistic identity, using the domestic sphere to explore harmony, resilience, and the anchoring force of everyday moments.

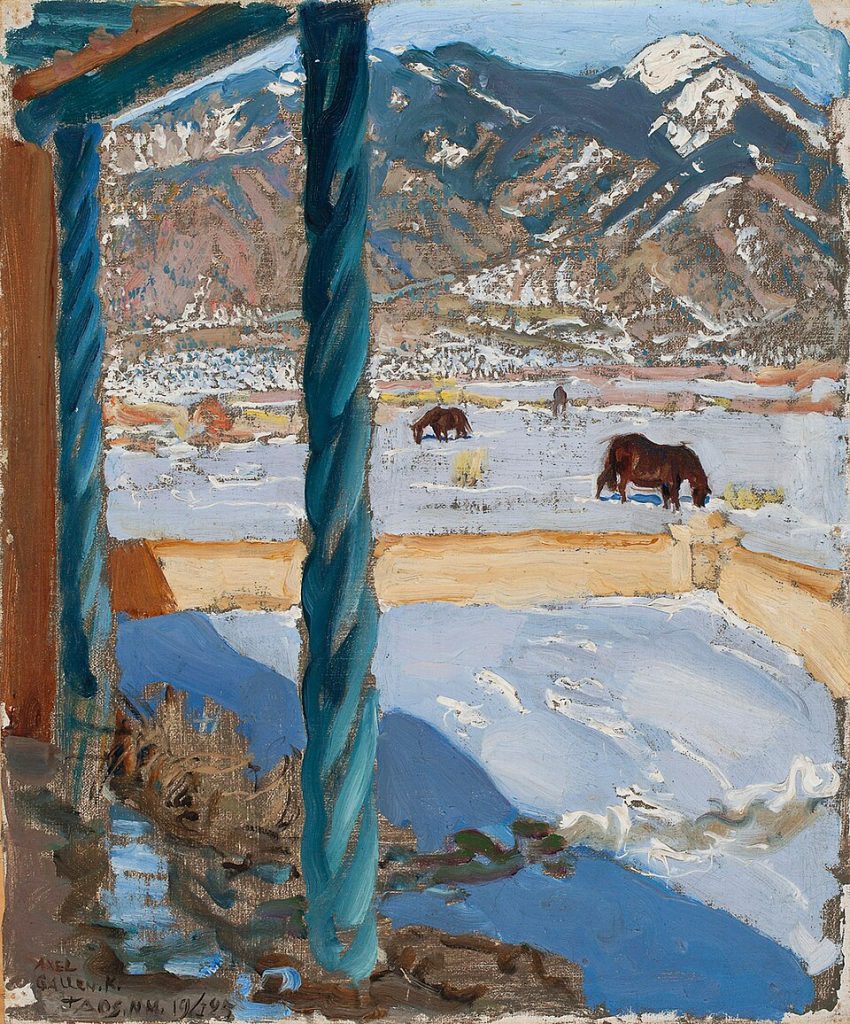

This painting dates to the time Gallen-Kallela spent in America (1923-1926), and in particular in the Taos art colony in New Mexico. The Native American art, the clarity of the high desert light, and the Pueblo architecture of Taos offered him a new visual language and renewed inspiration after the upheavals of the First World War and the Finnish Civil War. The painting depicts a sunny winter day in the New Mexican desert, as seen from the artist’s porch.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Taos Home in Sunlight, 1925, Ateneum, Helsinki, Finland.

Horses stand quietly in the snow‑covered yard, their small, dark forms anchoring the middle ground, while the distant mountains rise in luminous colors under the sharp desert light. The composition is simple, yet there is a fine balance between cool and warm tones that shows how the Taos landscape reshaped the artist’s sense of color, light, and structure once again.

The years following Taos Home in Sunlight marked the final chapter of Akseli Gallen‑Kallela’s long artistic journey. After leaving New Mexico in 1926, he returned to Finland with a renewed sense of clarity and purpose. His late work mainly comprised public commissions—most notably his fresco for the National Museum of Finland—and more intimate explorations of landscape and memory. Though his style no longer underwent the dramatic shifts of earlier decades, the final years revealed an artist who continually refined his pictorial language. When he died in 1931, Gallen‑Kallela had become not only one of Finland’s most famous painters but also a figure whose career embodied the tensions and aspirations of a young nation finding its modern identity.

“Finland’s National Painter: Akseli Gallen-Kallela,” Scandinavian Review, Spring 2007, 94, 3.

Charlotte Ashby: “Modernism in Scandinavia,” London, 2017.

Joe Martin Hill: “Inventing Finland,” Art in America, March 2007.

Rachel Sloan: “Gallen-Kallela: Helsinki, Paris and Düsseldorf,” The Burlington Magazine, 2012, Vol. 154, no. 1311.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!