Indus Valley Civilization: Echoes of a Forgotten Past

Nestled in the plains of present-day Pakistan and northwest India lies one of the world’s most enigmatic ancient societies: the Indus Valley...

Maya M. Tola 28 August 2025

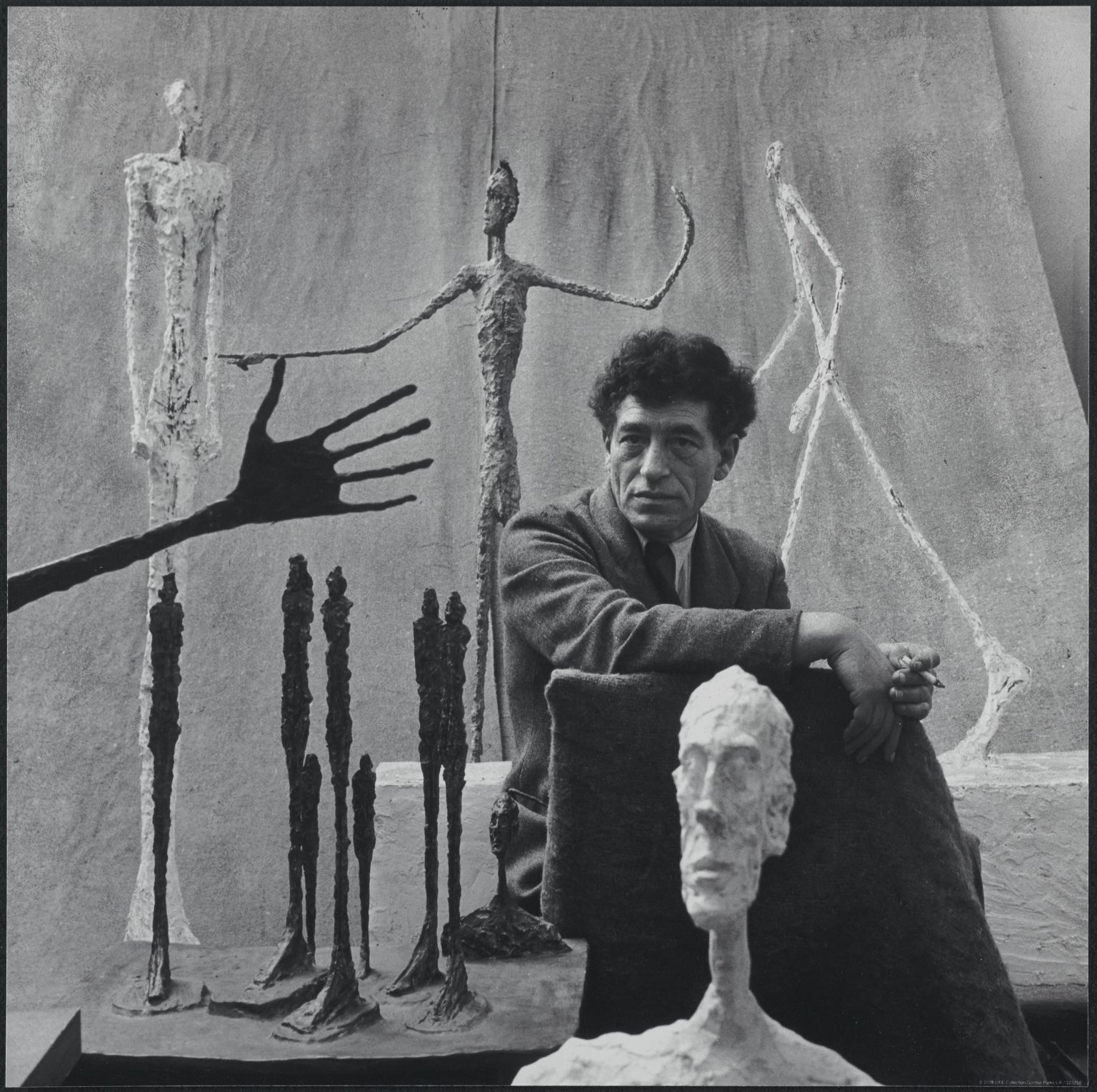

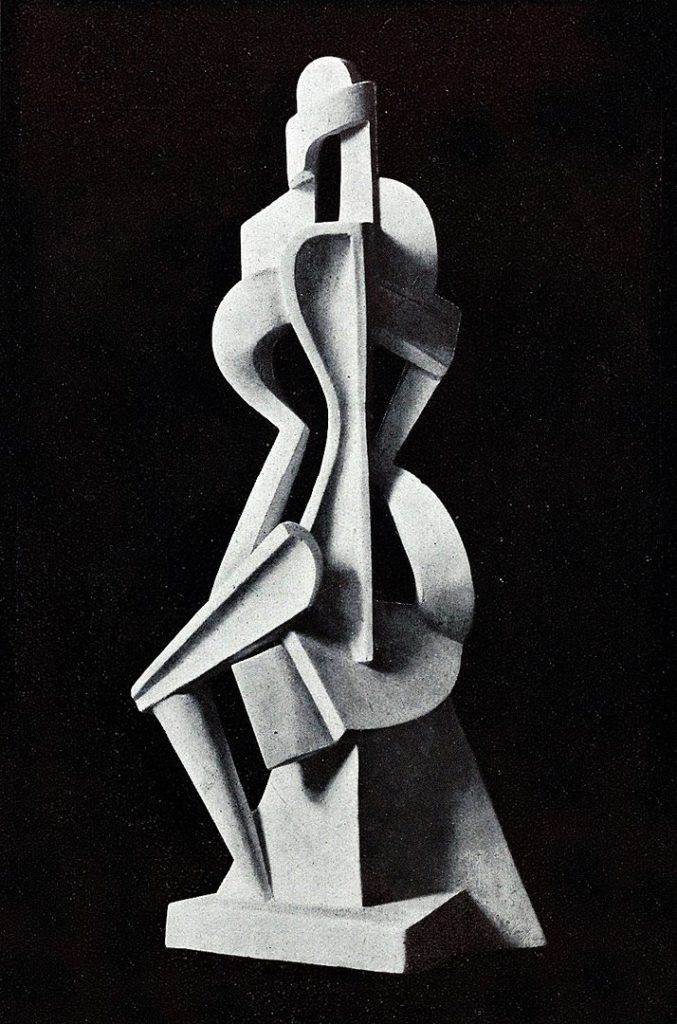

Cycladic figurines have a mythical aura. Their gleaming abstract forms speak of timeless beauty. But what actually are they? Why do they look like a Brancusi sculpture (or why do Brancusi sculptures look like them)?

…people thought the marble carvings from the Cyclades were ugly and vulgar. But not today. The abstract forms of the Cycladic figurines became fashionable and they have influenced many artists in the 20th century. They even continue to inspire contemporary artists today.

This came about at the end of the 19th century when artists began to delve into museums and ethnological collections. They were looking for inspiration from “primitive” civilizations so that they could return to the idea of essence and the supposed origins of creative possibilities.

Artworks became symbols or signs for what they represent. People began thinking that the Cycladic figurines were a universal reference to humanity. For the eyes of someone today, used to the idea of abstraction, it is no wonder that these artists were attracted to the forms of the Cycladic figurines. At the time, however, it was quite a turn of events for the ancient artifacts. The Western art world, which had previously been fixated on representational art, turned its gaze toward them. Consequently, they were elevated from their status as artifacts to artwork.

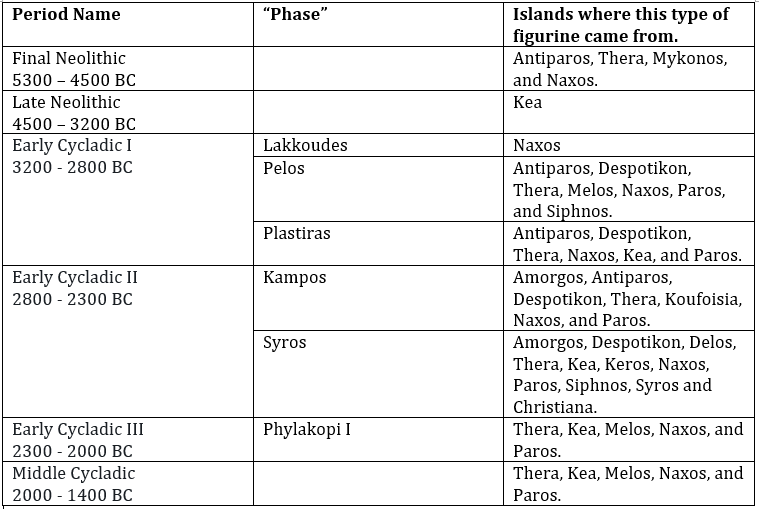

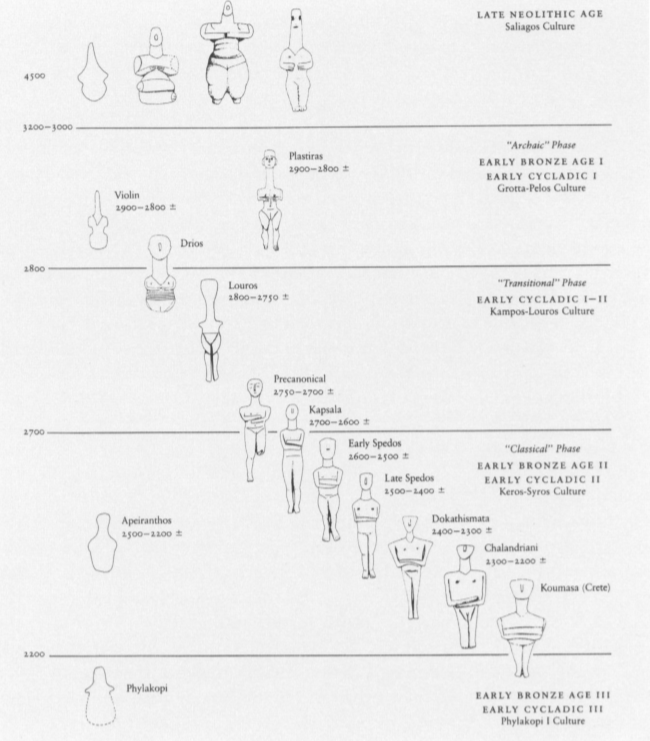

Generally, we might say that Cycladic figurines come from a society that existed about five thousand years ago. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. What we might recognize as a “Cycladic figurine” could come from quite a wide range of places and times, which scholars have divided into periods.

Firstly, there is the Early Cycladic (EC, 3200-2000 BCE, corresponding with the “Early Bronze Age”). Then, scholars distinguish three periods on the basis of things like settlements, techniques, and grave goods (aka the stuff we have): Early Cycladic I (EC I, 3200-2800 BCE), Early Cycladic II (EC II, 2800-2300 BCE) and Early Cycladic III (EC III, 23000-2000 BCE). Do bear in mind that these dates are pretty murky and the boundaries between our artificially imposed period are not discrete. Figurines are also found in periods on either side of the Early Cycladic: the Late Neolithic and the Middle Cycladic.

The Cyclades are a group of about thirty small Greek islands in the Aegean Sea. They sit between the mainland and Crete, the biggest Cycladic island.

Cycladic figurines, unsurprisingly, originate from this part of the world. What’s a little more complicated is that the society that produced them was not one homogenous group of people. The Cyclades are extremely tiny and have very limited resources. Consequently, each island community would have been small. There is evidence that there was travel by boat all around the Cyclades: moving resources, ideas, and people between each community.

Labeled groups of figurines will have existed at a particular time in a particular place. You won’t find all the figurines all over the place at all periods, which does make sense if you consider that the Cycladic period is a period of about 1200 years!

You can isolate types of figurines quite specifically to time spans and places. Some, like “violin types” (see a few paragraphs below) or the early “Plastiras” types, which have long necks are quite distinct in their form.

To be very generalist, at first (in the final Neolithic) we have quite plump figures (like the one below) and then increasingly the figures become more and more naturalistic.

Around the beginning of EC II (roughly 2800–2300 BCE) figurines that are now labeled “canonical” were being used. They have quite constant features, such as folded arms, flexed knees, tilted heads, and slanting feet. The “Kapsala” variety (see below) comes from a cemetery on Amorgos and is some of the earliest examples of what we now know as the canonical type.

The “Spedos” variety is the most prolific type of canonical figurine and has the most longevity. Most of the canonical figurines seem to be nude female figures, which researchers sometimes interpret as representations of the fertility of Chthonic goddesses.

Sometimes you’ll see figurines labeled with things like “Keros-Syros culture,” which is actually synonymous with “Early Cycladic II.” The latter label (EC II) is possibly clearer because not all figurines labeled “Keros-Syros culture” come from the islands Keros or Syros – such as this figurine, which was actually found on Amorgos.

This FAF figurine, which lives at the British Museum currently leads us to demystify phrases like “FAF type.” The above is a folded arm figurine, which abbreviates to FAF, which is a lesson in not being intimidated by scholarly terms because more often than not they are very simple! We’ve labeled what we see without imposing an interpretation. Are they cuddling a pregnant tummy or perhaps having tummy pains? What does the gesture mean?

“Violin types,” for example, have a weird shape that we can’t explain and so we’ve just named it after the object it brings to mind. Intriguingly, violin-type figurines are the most common type of representation of the human body in the Early Cycladic I period.

The Parian Marble FAF figurine is minimal and anthropomorphic (as is the Violin-shape figurine above). Our FAF from Amorgos is also heavy, so probably not practical to carry around, but it also can’t stand up by itself. This may not have been that ridiculous because it’s possible that this figurine was not intended for the living. On Amorgos, there are lots of cemeteries and many of them contain figurines.

We know this thanks to Greville-Chester. He was a vicar from the late 19th century who liked to travel around Egypt and the Cyclades collecting things, and, fortunately, recording their find-spots.

Finally, there is also the lack of legs, and, in fact, deliberately broken legs. This is not uncommon. On an island called Keros (where there are no settlements) there are two major deposits of figurines, known as the “Keros Hoard”. What’s really interesting is that the around 600 figurines are all in fragments and their breakage was deliberate. Was this a figurine dumping ground or (more tantalizingly) some kind of ritual activity?

Simple answer: we don’t know. As alluded to above, we don’t have very much contextual evidence from the Early Cycladic (3200-2000 BCE). Don’t get me wrong, there is plenty to get archeologists extremely excited about (tombs and pots for example), just not enough for a crystal clear understanding of day-to-day life for a person in those times or an exploration of religious beliefs.

Our primary sources are cemeteries and some bits of settlements. There is also not the same amount of evidence for all periods, for example, there are no settlement remains from Early Cycladic I (3200-2800 BCE) but lots of cemeteries and the reverse for Early Cycladic II (2800-2300 BCE).

Now, the astute reader will have noticed that this must mean the Cycladic figurines often come from graves (buried with people of all ages and gender). Which means, they were buried by people for other people. This also means it’s a bit weird to treat them solely like a piece of Giacometti sculpture.

They could be apotropaic, substitutes for sacrifices, companies for the dead, symbols of social status, cult items, or votive offerings… Interpretations are endless. Although we find them as grave objects, who knows how they were used in life?

Just because they were found in a grave doesn’t mean they were made for the grave. It’s still likely that these figurines were part of life. Exactly what part is, sadly, unclear. A word that might get associated with them is “ritual” – but, if we’re honest, that word is quite opaque and doesn’t really get us any closer.

The figurines are very tactile (think about the shape of an Oscar) and most of them can’t stand up on their own. It is very probable that they were personal objects of some kind. They do range in size though, from teeny tiny to ginormous; but whose to say that the different sizes don’t signify different purposes?

The figurine above is notable because it is 71.3 cm tall and would have been longer originally because it is broken at the knees. The breakage, for whatever reason, was embraced. With the ends of her legs being smoothed and rudimentary feet carved at the stumps. This kind of love and care is found in other broken figurines and suggests their symbolic, sentimental, and/or material value in the lives of the Cycladic people.

Our tall Female figurine of the Spedos variety seems to be gazing upwards, which is a posture not uncommon among Cycladic figurines. In fact, there is a great variety of poses and some really fun examples too. We have compositions of figurines playing instruments and even seated in groups. Unlike the generic figurines, these sculptures convey a sense of time and movement.

The “cupbearer,” for example, is a rare type of seated figurine. Scholars aren’t sure precisely why or what the sculptor is trying to show – a libation to some gods. Personally, I love the cup-bearer because I think it looks like someone having their morning coffee and people-watching in the sun.

Although gender is not a concern of the sculpture scholars tend to call this a male purely because it is a human in action. Similarly, we tend to think of Cycladic figurines as female based on schematic indications of female biological attributes. Such as those featured on the figurine below:

It has incisions indicating the arms, the pubic triangle, and the joints but an almost total lack of modeled features, such as breasts. It seems to have a swollen abdomen, which might imply pregnancy. Confusingly, many of the features we might regard as female (swollen belly, breasts, abdominal creases) can be found on figurines interpreted as male. This confusing (for us) mix of features is the norm, not the exception.

The Marble seated harp player (above) was included in The Met Museum’s “masterpieces” volumes in both 1993 and 2006 next to the likes of Modigliani.

Now, considering this is an object from an archeological site of unknown origin, that is quite a remarkable achievement. The fame and fortune do, however, come with some negative consequences.

Once the figurines transitioned from artifact to art they began moving all over the place. Essentially, once the art market started valuing them so highly their object status and context got pretty much totally lost. Sadly, we now only know the specific contexts for about 40% of the figurines, which means we’ve lost the corner pieces to our puzzle of working out their meanings.

In the 1980s there was even a scandal when someone did a study attributing “masters” to specific figurines; neither is this likely valid nor does it increase our understanding of the objects. It was a ploy designed to add monetary value. As in, looking at a “style” of the ancient figurines and deciding that a particular “artist” made it. Our figurine below, for example, is attributed to the “Bastis master,” whose “stylization of the human body that is elegant almost to the point of mannerism” – according to the MET allegedly). It goes without saying the “value” of such figurines tripled.

The number of forgeries also soared when the figurines became art. In part, this is due to the aniconic nature of our figurines. With very basic marble training almost anyone can fool the market. So long as you use a plausible Aegean marble, there is no way of checking the authenticity, especially since provenance has flown out the window when it comes to Cycladic figurines.

Interestingly, the Cycladic museum in Athens will buy Cycladic Figurines from the art market, calling it “rescuing” – with a view that the Cycladic figurines should stay in Greece (read Athens, not the Cycladic islands). An expensive business.

There is also the upside: the fame and glitter of the art world bring attention (and money) to these objects from a past society.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!