William Powell Frith

William Powell Frith (1819–1909) was a highly successful English painter of the Victorian Era. He specialized in social scenes, often depicting crowds. Though his name might not be especially familiar to audiences today—particularly outside of the United Kingdom—he was extremely popular in his time. In 1853, he became a member of the Royal Academy of Arts (the most prestigious art institution in England to this day), but his popularity wasn’t only within artistic circles. His artworks gathered large (paying) crowds, which made him something of a celebrity.

From an artistic perspective, Frith was a staunch traditionalist. He opposed new movements, such as the Pre-Raphaelites, which he publicly criticized on many occasions. However, he was very interested in depicting everyday scenes and, in particular, the different classes within Victorian society. He took inspiration from this, and many other things, from a very good friend of his—literature giant Charles Dickens (1812–1870).

A Masterpiece of Its Time

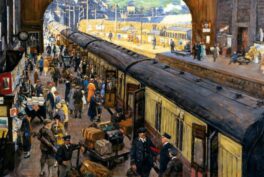

The Railway Station is one of Frith’s most well-known paintings. It depicts a scene at London Paddington train station. There are a number of versions of this painting. The main one, housed at Royal Holloway College in London, is also the largest, spanning over 2 meters (236 1/4 in.) in length. Frith also painted several smaller reproductions in his life, including one currently part of the Royal Collection, which you can see here.

In many ways, this painting exemplifies Frith’s preferences and artistic interests. It is a genre painting, depicting all Victorian social classes in one setting. It is a chaotic scene, befitting the moment it is depicting. There are travelers rushing to board a train that seems to be nearly ready to depart. Above them, workers finish loading the luggage. Within the chaos, there are many stories unfolding in front of the viewer, each with its own individuality.

Though there is no immediate focal point, one of the first scenes capturing the viewer’s attention is in the centre-left of the frame. Here, a mother is kissing her young son, who is holding a cricket bat in his right hand (presumably as he prepares to leave for a summer school). Her husband and older son wait behind them. The models for this scene were in fact Frith’s own family.

Next to them is a towering figure—a man with a long beard who looks somewhat out of place, as if unsure of his surroundings. The inspiration for this character was a Venetian refugee who gave Italian lessons to Frith’s children. In the scene, a cab driver is harassing him as he demands payment.

Yet it is the scene on the far right that takes the viewer by surprise. It depicts a man being arrested as he tries to board the train. It is hidden, and yet in plain sight. The men behind him are stopping him—one physically pulling him down, while the other waits with a pair of handcuffs. It is a surprising scene for a picture that is otherwise dominated by people rushing and heartfelt goodbyes.

The Age of the Railway

Central to the painting is of course the railway itself. This Victorian innovation allowed a disparate group of people to come together and travel toward a shared destination. It was an extremely topical matter, which Frith exploited to give relevance to his artwork.

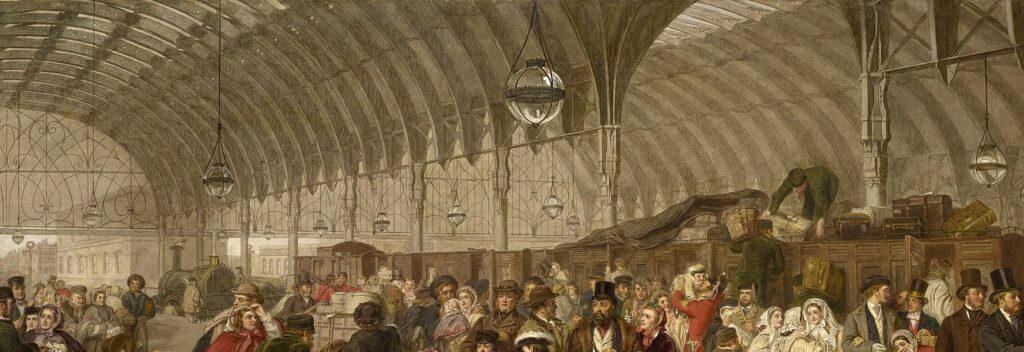

Using trains as a form of mass travel was, at the time, a breakthrough. The Victorian Era was rich in large-scale civil projects. Victorians bought into the vision of a newly connected England through an expanded railway network without reservation. It opened new opportunities and was a strong proof of the innovation leaps that England was able to take thanks to the Industrial Revolution.

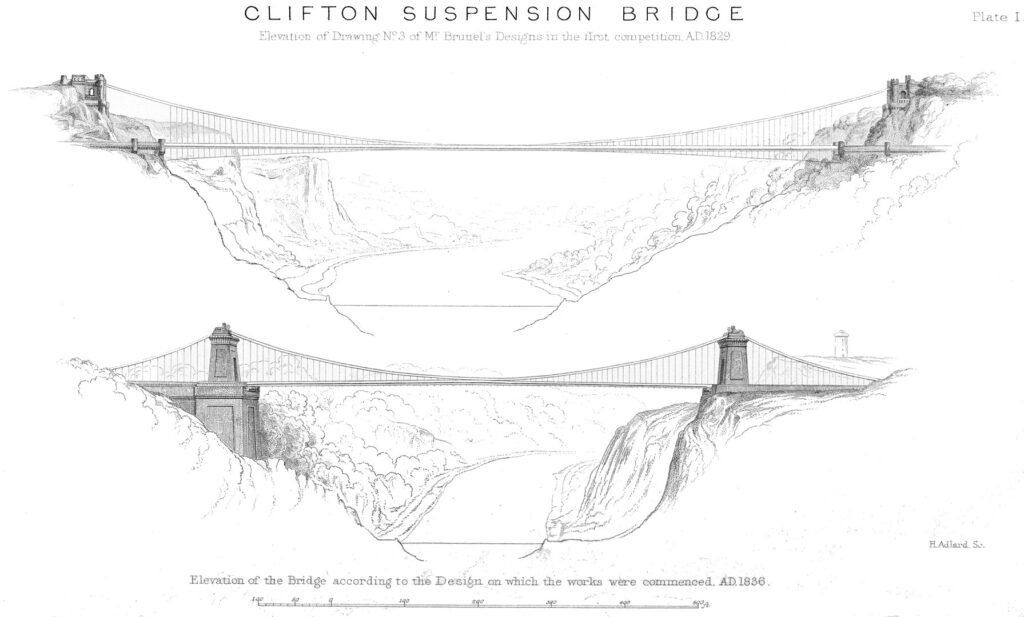

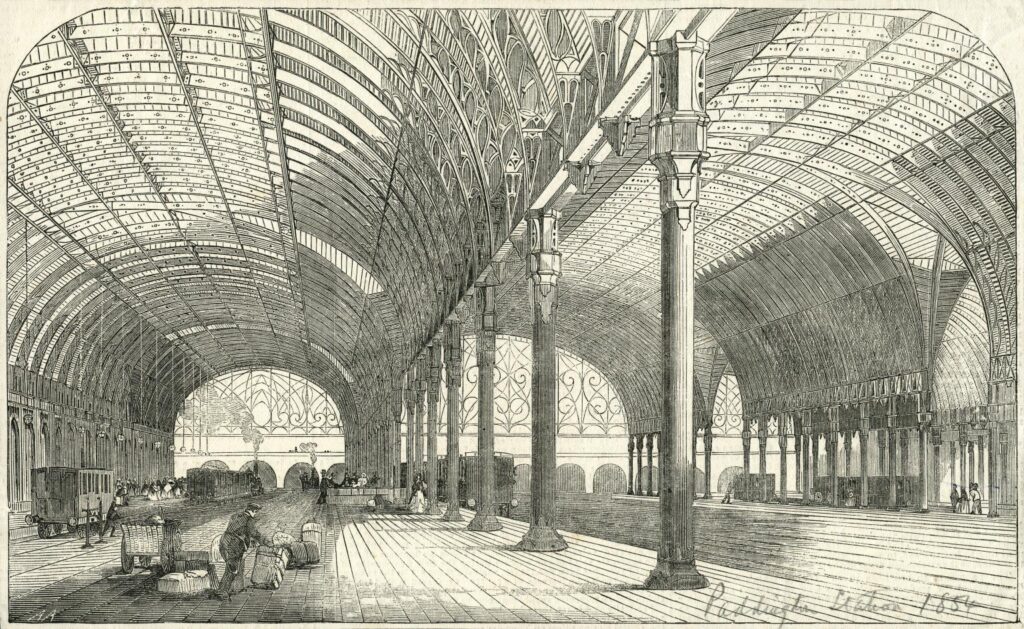

The fact that the scene unfolds at London Paddington specifically is also far from coincidental. Paddington Station opened in 1854, less than a decade before The Railway Station by Frith was completed. It was designed by celebrity engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859). He was the mind behind some of the most daring engineering projects of the time, such as the Thames Tunnel in London and the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol (to this day one of the oldest functioning iron suspension bridges in the world).

Paddington Station was the engineering masterpiece that was supposed to herald the new era of steam and iron. Brunel himself, who lived in the West of England, wanted to give the West Country the railway network and connection to London it deserved. As such, he designed Paddington station to be not only the home of the new Western rail network, but also London’s busiest, largest, and most modern hub. Frith cemented the reputation of London Paddington by making it not just a backdrop but a co-protagonist in his painting.

An Artwork for the Masses

Among its many achievements, The Railway Station also marks a novel way to display art. By 1862, Frith was a well-established artist. He was a Royal Academician with some iconic masterpieces already under his belt, such as Ramsgate Sands and The Derby Day. The expectations of and public interest in Frith’s work were palpable. The public wanted Frith—and he wasn’t going to shy away from it.

The Railway Station was first shown in a one-painting-only exhibition in London, which is said to have gathered paying crowds of over 20,000 people. This was the beginning of a new way of conceiving and displaying art—art made for the entertainment of the masses, rather than for the refined taste of a selected few. Although he was artistically traditional, Frith adapted willingly to this new concept for displaying the work. His artwork was accompanied by a pamphlet, that guided the audience through the picture and helped with its interpretation, helping them feel part of the event.

Frith exploited tastes, fashions, and his own popularity at the time to his advantage—making him wealthy and successful in ways other artists could have never imagined. Perhaps precisely because of its popularity with the masses, his artwork was poorly received by art critics at the time, who lamented a supposed lack of finesse and artistic merit. However, The Railway Station remains an iconic symbol of art in the Victorian Era, by one of its most accomplished painters.