Rachel Ruysch in 5 Paintings

Rachel Ruysch was a Dutch still-life artist renowned for her elaborate and lifelike floral paintings. Her talent earned her a position as a court...

Nikolina Konjevod, 3 June 2025

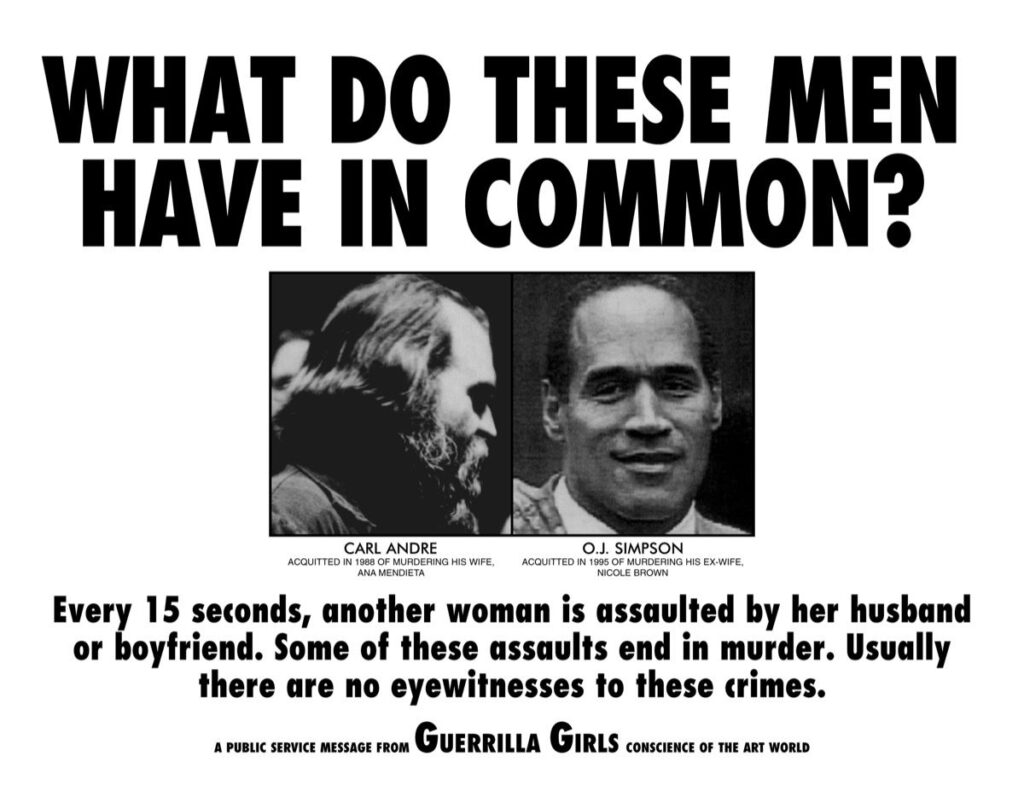

“Where is Ana Mendieta?” was shouted in 1992 by over 500 protesters in front of the newly-opened Guggenheim Museum site in SoHo, New York. (The space would be permanently closed in 2001.) The Guggenheim branch’s inaugural show already stirred outrage with works from only white artists and a gender imbalance of five men and one woman. Yet including Carl Andre (1935-2024) in it was the last straw. Why would that be? The minimalist sculptor has been subject to an accusation. That is, killing his wife and fellow artist, Ana Mendieta. Mendieta’s death remains a mystery, even after the court acquitted Andre in 1988.

The Guerrilla Girls and the Women’s Action Coalition (WAC) were organizations supporting the 1992 protesters. As the congregation in front of Guggenheim SoHo gained momentum, it gave rise to a movement titled WHEREISANAMENDIETA, which has been exposing the systemic erasure in art and cultural institutions of works from women, non-binary people, black people and other people of color among the oppressed and marginalized ever since.

As Mendieta was turned posthumously into an icon of social justice, Coco Fusco, a Cuban-American artist, curator, and friend of Mendieta, expressed her concern:

All of the post-mortem canonization has nothing to do with how she lived or how she was treated during her life. I think she’s become a symbol used by many people to address sexism in the art world through personal attacks directed at Carl Andre. Many younger artists exploit the memory of Ana for their own professional advancement.

Coco Fusco in an interview with Jared Quinton, 2016, Artsy.

It might be time to reconsider Mendieta and her entanglements with social activism in light of her life and her work.

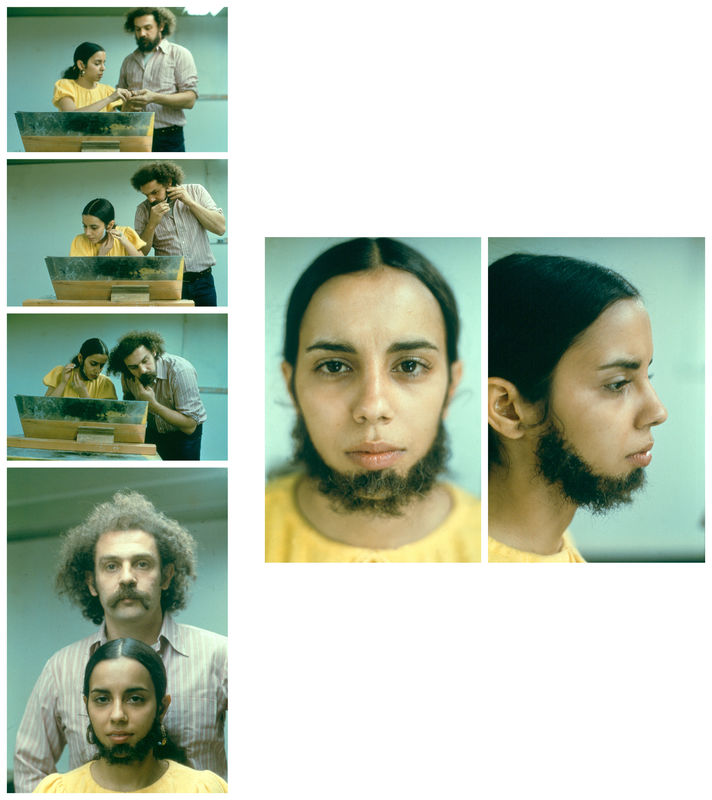

Since her graduation project at the University of Iowa, Mendieta knew how she wanted her art to progress: Untitled (Facial Hair Transplant), her first published work, interrogated the gender binary by gluing her colleague’s facial hair to her chin and, thus, creating a rupture in the social conventions that had framed gender expressions. In 1972, this was a powerful gesture; it remains thought-provoking, while gender has become a much more complex topic today.

Gender roles and the beauty standards they entail continued to be constant themes in Mendieta’s art. “Earth Body” is the expression associated with her. It might describe an individual’s body like that of hers wrapped in soil and unified with the surroundings in The Tree of Life. It might allude to something more subversive as she delved into the gender troubles, particularly those in the form of male violence against women. But fundamentally, Earth Body summarizes her artistic ponderings around self-awareness and humans’ relations with the planet Earth. Through performance, she embodied these thoughts—even though there might be an absence of a physical body—In her Silueta series, for example, Mendieta focused on symbolic bodies: landscapes, outlines, and their spectral qualities. These sign vehicles for her were “a way of reclaiming [her] roots and becoming one with nature” and her identity as an uprooted person:

My exploration through my art of the relationship between myself and nature has been a clear result of my having been torn from my homeland during my adolescence. (…) Although the culture in which

I live is part of me, my roots and cultural identity are a result of my Cuban heritage.Unpublished notes by Mendieta, quoted in Charles Merewether, From Inscription to Dissolution: An Essay on Expenditure in the Work of Ana Mendieta, in Coco Fusco, ed. Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 131.

Mendieta became a refugee when she was 12. She and her sister were part of Operation Peter Pan, which sent Cuban children to the US to avoid the rumored indoctrination centers during Fidel Castro’s regime. Due to the secrecy of the program and their father being a political prisoner, the girls departed unattended for Iowa in 1961. As a US citizen, Ana Mendieta became involved in El Diálogo in the 1970s, when Cuban exile groups attempted to reach a rapprochement with Cuba through negotiations. However, a family reunion did not happen until ten years later, in 1980. As she set foot in Cuba again, Mendieta established herself as a voice of Cuban artists in diaspora and an intermediary between her US friends and the Cuban locals.

Much of Mendieta’s art is deemed ritualistic, as it often elicited the occult and folk traditions from her beloved Mexico (where she often traveled), as well as Cuba. To some, her love for spirituality (contrary to the material world) seems a premonition of her death. On September 8, 1985, Mendieta, 36, fell out of the window of her apartment on the 34th floor. Her husband Carl Andre called the police, stating that “Ana went out of the window.” Despite Andre’s insistence that he remembered nothing and Mendieta had committed suicide, his inconsistent testimonies were at odds with that of the neighbors, who reported hearing the couple quarrel. And Mendieta’s friends, who recalled her fear of heights and her professional achievements at that point, doubted she would have jumped in her underwear out of depression or despair.

Three years after the tragedy, the court acquitted Andre based on insufficient evidence. Carl Andre passed away in January 2024, aged 88.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!