Masterpiece Story: Sistine Madonna by Raphael

We’ve seen them on postcards, gift wrap, T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even tattoos. With their serene expressions and relaxed posture, Raphael’s...

Javier Abel Miguel 8 February 2026

The complex of the Santi Apostoli basilica in Rome, located just steps away from the bustling Piazza Venezia, is a place steeped in history. If you wander into the adjoining cloister—a space remarkably intimate and serene compared to the chaos of the city center—you will find, nestled among ancient tombs and weathered marble inscriptions, a cenotaph dedicated to Michelangelo Buonarroti.

Wait a moment—a cenotaph? Indeed. A funeral monument where the body of the deceased is conspicuously absent. But why would it be absent if Michelangelo is famously buried in the Santa Croce basilica in Florence? Well, let’s start from the beginning.

Michelangelo Buonarroti passed away in Rome on February 18, 1564, just weeks shy of his 89th birthday. He died in his modest residence at Piazza Macel de’ Corvi, near Trajan’s Forum. It was shortly before five o’clock in the afternoon when the master breathed his last. Legend has it that he had been working on his final masterpiece, the Rondanini Pietà, almost until the very end.

Immediately after his death, a fierce dispute arose over his final resting place.

Michelangelo, Rondanini Pietà, 1564, Sforza Castle, Milan, Italy. Photograph by Paolo da Reggio via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Even though Michelangelo was a Florentine, he had spent the last three decades of his life in Rome. While he had always expressed a wish to be buried in his hometown of Florence, the Romans—who had come to regard Buonarroti as their own—were unwilling to let him go. Consequently, his mortal remains were moved the following day to the Santi Apostoli basilica in a solemn procession attended by the whole of Rome. Pope Pius IV himself began planning a monumental tomb in St. Peter’s Basilica.

Giacomo del Duca, Cenotaph of Michelangelo, Santi Apostoli, Rome, Italy. Photo: Michelangelo Buonarroti è tornato.

However, the Florentine elite would not accept this loss. When Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici heard of the Roman plans, he was resolute: having been unable to bring Michelangelo back to Florence during his life, he would ensure the artist was honored in death with a state funeral and a magnificent tomb in his native city. With the Pope determined to keep the body, and the Duke determined to claim it, there was only one way forward: Michelangelo’s body would have to be stolen.

Lionardo Buonarroti, Michelangelo’s nephew and heir, was entrusted with the delicate and dangerous task. Upon Lionardo’s arrival in Rome on February 24, 1564, a clandestine strategy was devised to smuggle the remains out of the city. The risk was high: if the Roman authorities or the Pope’s men discovered the plot, the consequences would be severe.

Francesco Furini, Michelangelo sul letto di morte, 1628, Casa Buonarroti, Florence, Italy.

Under the cover of darkness and in total secrecy, the body of the revered sculptor, painter, and architect was removed from its temporary tomb in Santi Apostoli. To bypass Roman guards and avoid a public outcry, Michelangelo’s body was carefully wrapped in a bale of hay and disguised as common merchandise. Loaded onto a cart alongside other goods, Michelangelo left the Eternal City as a humble shipment of freight.

It was a cunning plan. By the time anyone in Rome—including the Pope—could realize the grave was empty, the cart was already crossing the border from the Papal States into the Duchy of Florence. The master was finally on his way home.

The body of Michelangelo finally arrived in Florence on March 10, 1564. It was first placed in the Chapel of the Assumption, where it remained for two days before being transported to the Santa Croce basilica. An immense crowd filled the streets, lit by the flickering glow of torches, to welcome their greatest son home.

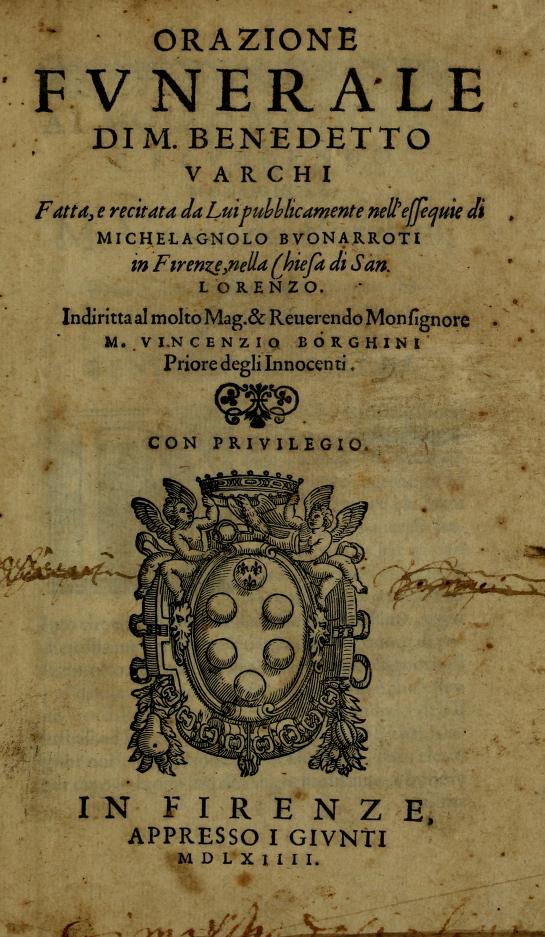

Title page of the 1564 Giuntina edition of Benedetto Varchi’s funeral oration for Michelangelo. Storia di Firenze.

Upon reaching the church, the body was carried into the sacristy for the opening of the casket. Those present expected to face the grim reality of death, as Michelangelo had been dead for 25 days. However, to the amazement of every witness, they found the body perfectly intact, showing no signs of decay or decomposition. Instead, the master appeared as if he were merely resting in a “sweet and most tranquil sleep.”

Cosimo I de’ Medici spared no expense in honoring the great artist. On July 14, 1564, after several delays, Michelangelo’s funeral was finally held at the Basilica of San Lorenzo. The interior was draped in black cloth and adorned with ephemeral paintings and sculptures celebrating the master’s life and work. As Giorgio Vasari himself wrote: “Florence would bid farewell to no Pope or Emperor as it did to Michelangelo, its prodigal son.”

Giorgio Vasari (project), Tomb of Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1564–1576, Santa Croce, Florence, Italy. Santa Croce.

Following the ceremony, the body was laid to its final rest in the Basilica of Santa Croce, inside a magnificent tomb designed by Vasari. Located at the beginning of the right nave, the monument stands as a permanent testament to his genius. The design incorporates traditional symbols and imagery reflecting Michelangelo’s career. Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture are personified as three mourning muses, weeping for the loss of the man who mastered them all.

Michelangelo, finally, was home.

Valerio Cioli, Sculpture from the Tomb of Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1564–1574, Santa Croce, Florence, Italy. Detail. Santa Croce.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!