Art and Life in Rembrandt’s Time at the Norton Museum of Art

Thomas Kaplan and his wife, Daphne Recanati Kaplan, have amassed the world’s largest private collection of 17th-century Dutch paintings. The...

Tom Anderson 5 February 2026

Written by Holocaust survivor Suzanne Loebl with Abigail Wilentz, Plunder and Survival (Bloomsbury, 2025) traces the Nazi looting of art across wartime Europe. Moving between key figures, events, and emblematic artworks, Loebl guides the reader through this intricate history while drawing on her own experience to show what cultural destruction looked like from within.

As a firsthand witness to Nazi persecution, Suzanne Loebl’s writing is marked by sensitivity and emotional intensity. She threads her own family story into a narrative that is as compelling as it is detailed—first as a Jewish child in Germany, then as a teenager in hiding in Belgium during the Holocaust, and later as an immigrant to the United States. Her life story makes her uniquely placed to tell it with both moral authority and a historian’s attention to detail.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907, Neue Galerie New York, New York City, NY, USA. This portrait is undoubtedly the Nazi era’s most famous looted artwork. Its restitution to Adele’s heirs made judicial history.

Rather than offering a catalogue of stolen masterpieces, Plunder and Survival approaches Nazi art looting through its human side. Loebl follows three intersecting threads—collectors and families who lost their works, the dealers and officials who stole and profited from them in Hitler’s service, and the people who tried to save what they could—while paying particular attention to the pieces that crossed the Atlantic and the American networks that took them in.

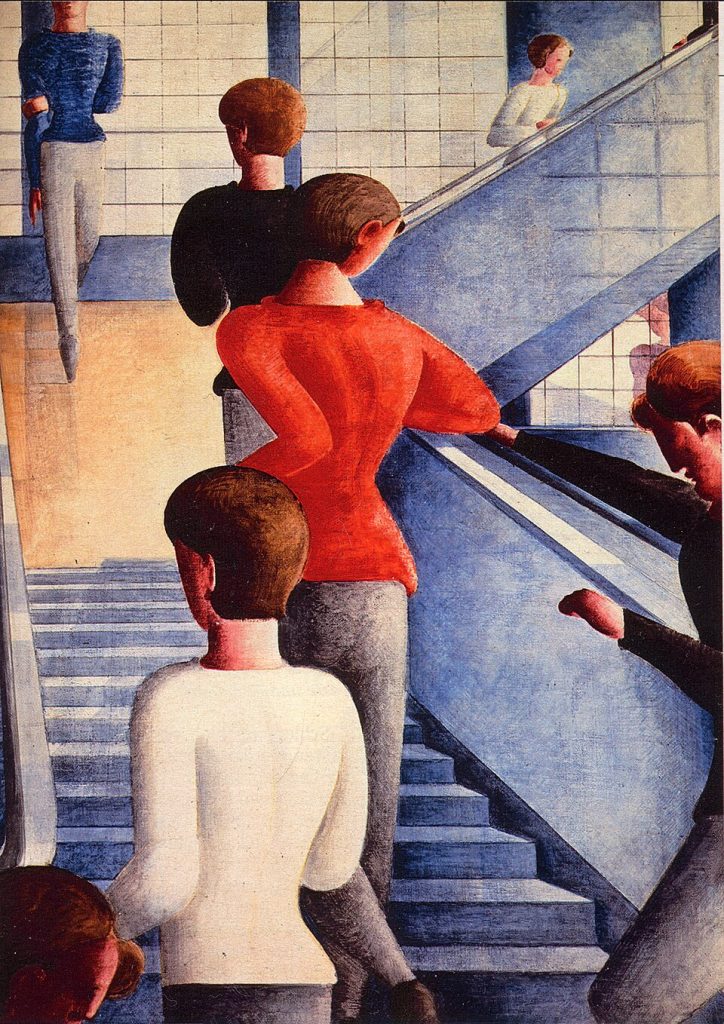

Oskar Schlemmer, Bauhaus Stairway, 1932, Museum of Modern Art, New York City, NY, USA. At the request of Alfred Barr, Philip Johnson bought the work in Germany and eventually donated it to the Museum of Modern Art.

Loebl shows that Nazi art theft was not a series of isolated crimes but an organized, cross-border system. She makes clear the scale of the plunder—with hundreds of thousands of objects in her accounting—and shows how confiscations reached museums and private homes. She details the fragile routes of flight taken by refugees, dealers, and artists across occupied Europe, from confiscations in Austria and France to high-profile seizures in the Netherlands. The result is a clear picture of transport routes, storage depots, and how dispossession became bureaucracy and profit.

Salomon van Ruysdael, River Landscape with Ferry, 1649, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA. Alois Miedl and Hermann Göring took over Jacques Goudstikkers’s Gallery in Amsterdam and disposed of its inventory.

Against that backdrop, Plunder and Survival frames looting as part of a wider cultural project—the Nazi assault on modernism. Loebl explains how the label “degenerate art” worked as an ideology disguised as taste, used to purge institutions and target styles such as Expressionism. The 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich emerges as a key moment in the book, a public spectacle designed to ridicule artists and movements that had been gaining recognition only a decade earlier.

Loebl also highlights the “sales machine” behind these confiscations—a network of dealers appointed to handle museum seizures. This enabled the regime to pursue two goals at once—eradicating modern art at home while exploiting it abroad as a source of currency.

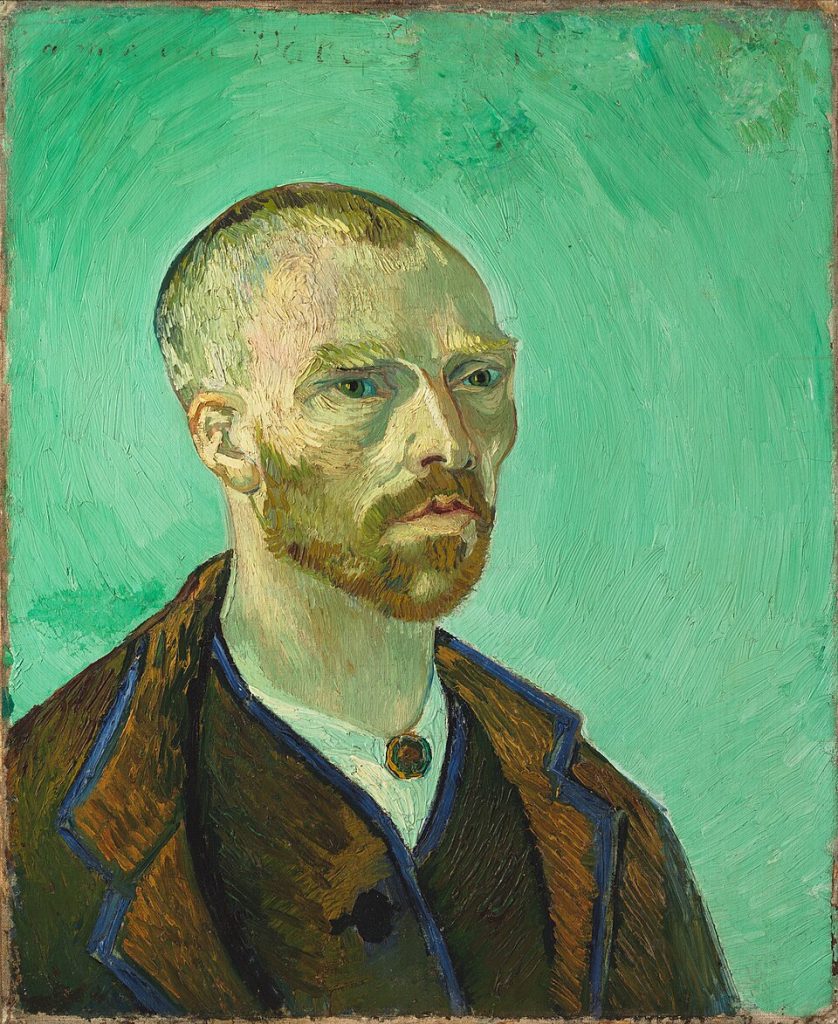

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin, 1888, Fogg Museum, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, USA. The painting was auctioned in Lucerne in 1939.

What makes Loebl’s approach distinctive is her attention to the people around the artworks: the owners forced to sell or flee; the dealers and officials who stole and monetized what was taken; and the intermediaries who helped save what they could. She follows the journeys of what she calls “migrant” art—works that crossed the Atlantic alongside displaced artists, curators, and dealers—shifting the art world’s centre toward the United States. The book closes by tracing the long, uneven path of restitution, from postwar recoveries to the renewed momentum of the 1990s and the Washington Principles, underscoring that many cases remain unresolved and continue to surface today.

Loebl’s book is meant to be read both for its narrative momentum and its documentary value. It moves at a brisk pace, taking the reader from one case to the next while weaving in personal episodes that add immediacy without overshadowing the historical context. Its approach is deliberately panoramic, blending broader historical sections with real-life cases that help make the story, and its scale, visible. At times, that breadth means some figures are sketched only briefly, but it also helps to convey the enormity of the plunder.

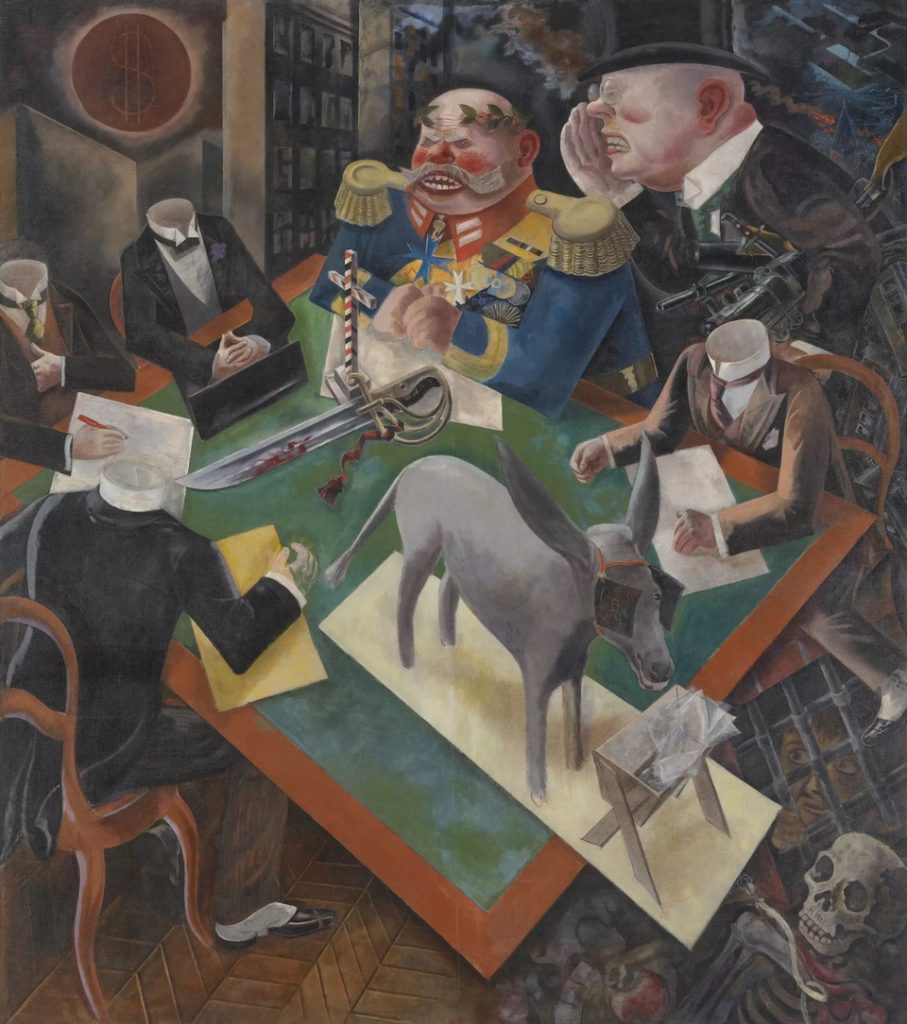

Georg Grosz, Eclipse of the Sun, 1926, Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, USA. The painting arrived in the United States in 1932 with an asylum-seeking Grosz.

For support, the book includes genuinely useful material, especially appendices indicating where many of these works are displayed today in U.S. museums, which adds to its appeal for readers interested in provenance and restitution. Overall, it’s an accessible, absorbing account that leaves a very contemporary question hanging in the air—how much “unresolved” art history is still hanging on museum walls today?

I hope you will read Plunder and Survival despite its tragic background. Beyond theft and violence, the book is a testament to the people who, in different ways, fought to protect art and culture. Loebl opens a window onto a tragic yet fascinating chapter in art history and invites us to explore it through her own experience.

Plunder and Survival: Stories of Theft, Loss, Recovery, and Migration of Nazi Uprooted Art by Suzanne Loebl with Abigail Wilentz was published in October 2025 by Bloomsberg. You can get a copy of the book through the publisher’s website.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!