Camille Claudel in 5 Sculptures

Camille Claudel was an outstanding 19th-century sculptress, a pupil and assistant to Auguste Rodin, and an artist suffering from mental problems. She...

Valeria Kumekina 24 July 2024

Minnie Pwerle stands as a pivotal figure in the realm of contemporary art, leaving an enduring legacy through her vibrant and dynamic works. Her art serves as a conduit to the rich traditions and spiritual essence of the Anmatyerre people of Australia’s Northern Territory, evoking a timeless energy and profound connection to the land and Dreamtime stories.

In his seminal work The Songlines (1987), Bruce Chatwin delves into the intricate ways Australian Aboriginal tribes utilize chants, symbols, and seemingly abstract artworks to narrate the ancestral tales of their people. In the book, the British author explains how these stories serve as both descriptions of tribal homelands and foundational myths, and how they are used as a baseline for chants along with body paint works, rock drawings, and more traditional forms of visual expression.

In regards to the practice, the works of the indigenous Australian artist Minnie Pwerle are perfectly ascribed. Drawing upon the rich traditions and spiritual connection of the Anmatyerre people of the Utopia region in the Northern Territory of Australia, Pwerle used bold colors and expressive brushstrokes, infusing her paintings with a timeless energy and a profound connection to her land and Dreamtime stories.

Despite approaching painting only at a late age, she was extremely prolific and swiftly emerged as one of the most representative artists of her generation and of Australian Aboriginal art. Nowadays, her works are collected worldwide and she is represented in the major galleries and museums of Australia and abroad, while her legacy is strong and keeps influencing younger artists, both indigenous and international.

Minnie Pwerle with one of her paintings. Aboriginal Art.

Little do we know about Minnie Pwerle’s early life. Born somewhere between 1910 and 1922, Pwerle hailed from the Anmatyerre and Alyawarre Aboriginal language groups, growing up amidst the remote desert landscapes of central Australia. She lived in Utopia, Northern Territory (Unupurna in the local language), a cattle station in the Sandover area of Central Australia, around 300 kilometers northeast of Alice Springs.

Raised in a traditional Aboriginal lifestyle, Pwerle’s early years were steeped in the cultural practices and stories passed down through generations. Despite not starting her artistic career until the late 1970s, Minnie Pwerle’s journey into the art world was a natural extension of her cultural heritage and her deep connection to the land.

Around 1945, Minnie Pwerle had an affair with a married man possibly of Irish descent, Jack Weir, and the couple had a child together, Barbara Weir. The relationship between Minnie and Weir was illegal at the time, and the pair were jailed for a while. Around the age of nine her daughter Barbara, considered ‘half-caste’, was taken from Minnie by the Native Welfare Patrol, and the artist did not see her again until many years later when Weir returned to Utopia to re-discover her heritage. Barbara Weir is now a well-known Aboriginal artist, and she inspired her mother to pick up painting herself. Pwerle went on to have six more children with her husband “Motorcar” Jim Ngala and lived her entire life in the Utopia region.

Minnie Pwerle, Awelye – Anemangkerr (Bush Melon). Japingka Aboriginal Art.

Around 1999-2000, when Pwerle was almost 80, she began painting on canvas, encouraged in her practice by her daughter and her niece Emily Kame Kngwarreye, both accomplished artists in their own right. Drawing inspiration from her cultural heritage and the Dreamtime stories of her ancestors, Pwerle’s art quickly gained recognition for its distinctive style and powerful imagery. Her work became so popular that the artist was allegedly “kidnapped” by people who wanted her to paint for them, and there have been media reports of her work being forged.

Active and in spirit well into her 80’s, Pwerle painted an incredible number of works and had a significant impact on the Australian Aboriginal art movement. Her artistic career was meteoric but very successful nonetheless, with her paintings exhibited in galleries and museums around the world. She continued to paint prolifically until her passing in 2006, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and captivate audiences globally.

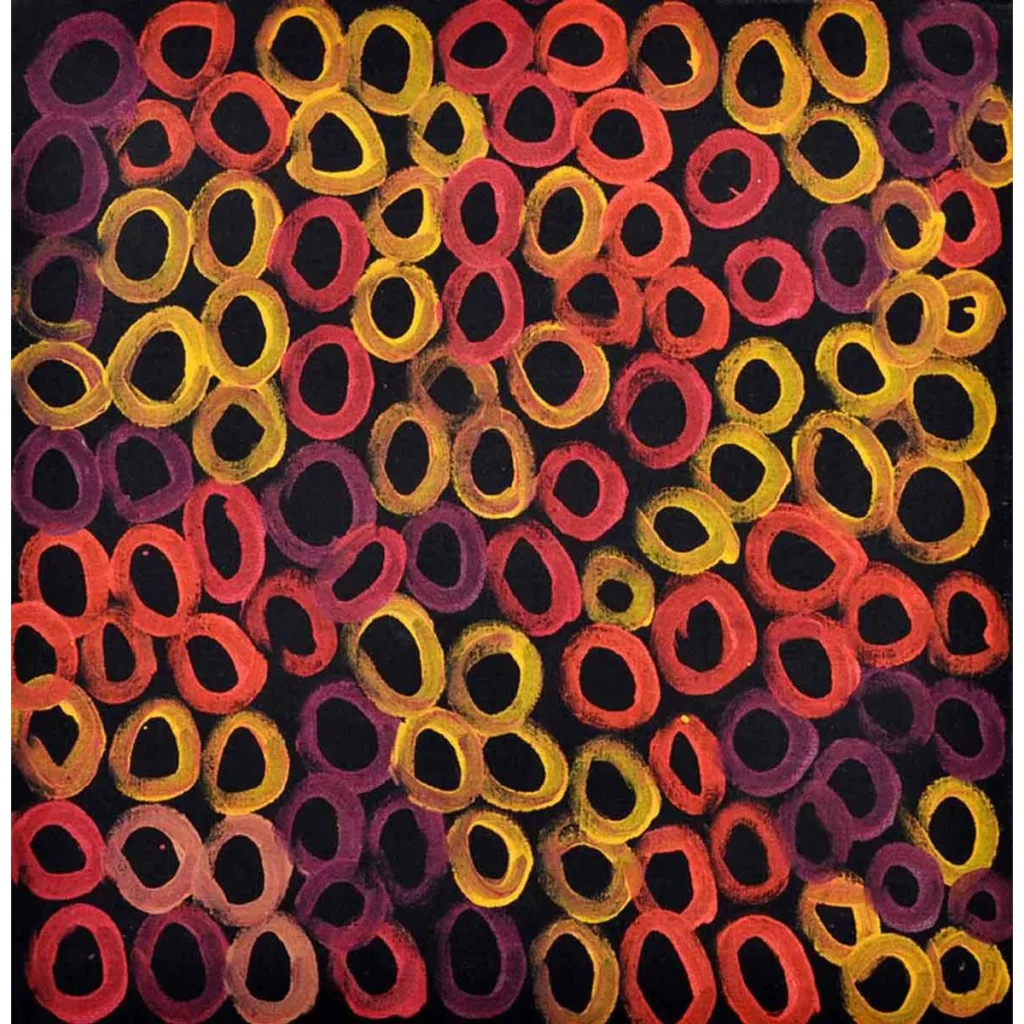

Minnie Pwerle, Bush Melon Seeds A6170, acrylic on linen, 60 x 60 cm, 2005. Photo Mitchell Fine Art.

Minnie Pwerle’s paintings are spontaneous and highly personal. Despite drawing on the indigenous traditions, Pwerle was able to establish a personal style that was at once reminiscent of her ancestors’ work and also greatly innovative.

Characterized by a bold use of color, rhythmic patterns, and dynamic compositions, Pwerle’s style is distinctively abstract. Her work has been described as part of the gestural abstractionism movement inside Indigenous art, following in the footsteps of Emily Kngwarreye and other Western Desert artists.

Deeply rooted in the spiritual and cultural traditions of her people, Pwerle’s work seeks to convey the essence of the Dreamtime stories that have been passed down through generations, as well as the artist’s personal connection to the land, including the Awelye (women’s ceremonial body paint designs) and Atnwengerrp (bush melon) Dreaming. Pwerle was likely the designated keeper for these stories within her family or clan, which granted her not only the permission to tell or represent the stories but also the knowledge to pass them down to younger generations.

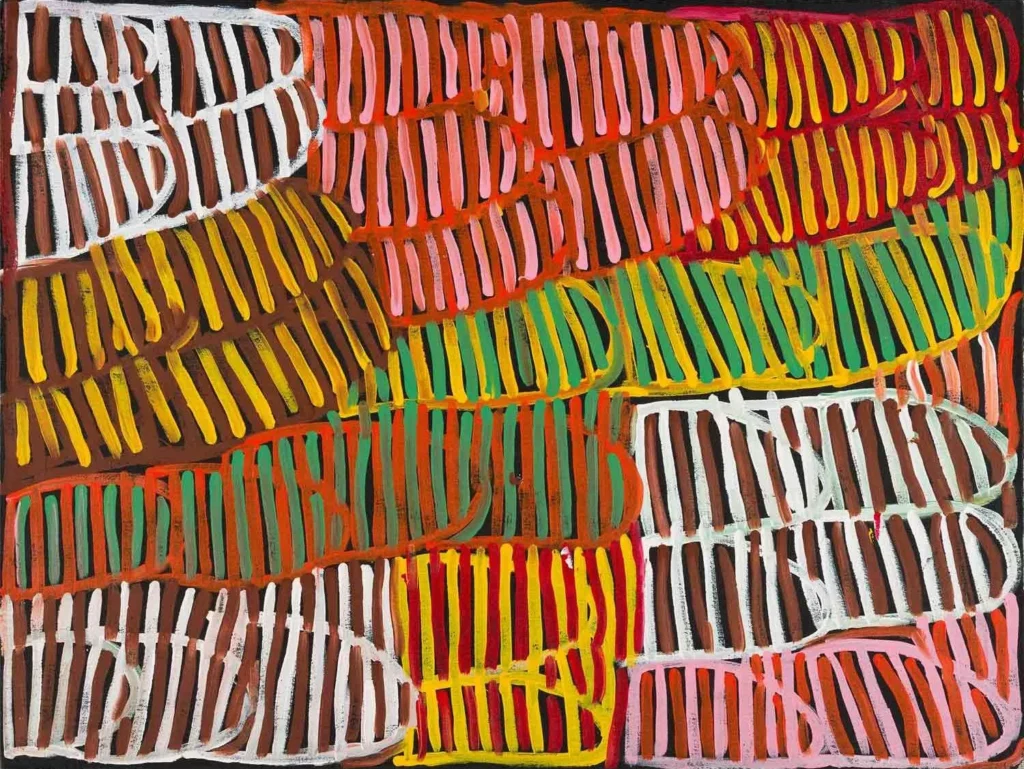

Minnie Pwerle, Awelye (Body Painting) A6240, 2005. Mitchell Fine Art.

One of the most striking aspects of Pwerle’s work is her masterful use of color along with the sense of movement and energy coming from her designs. Vibrant hues of red, yellow, blue, and green leap off the canvas, and the colors are often applied in bold, gestural strokes, imbuing the paintings with a sense of vitality and dynamism.

In many of her works, Pwerle employs repetitive patterns and motifs, which are reminiscent of Aboriginal rituals. These intricate designs are more than mere adornments; they carry deep cultural significance and are imbued with layers of meaning that speak to the interconnectedness of all living things.

Among those patterns, two main design themes can be recognized. Some works are characterized by free-flowing and parallel lines, which recall the body painting designs used in women’s ceremonies, or awelye. Another group of works, on the contrary, employs circular shapes, used to depict different forms of bushfood, local fruits and vegetables that spontaneously grow in the region.

Using these distinctive motifs and captivating colors, the artist’s compositions often convey a sense of rhythm and flow, as if the paintings themselves are alive with the spirit of the land. Lines zigzag and intersect, creating a sense of movement and energy that draws the viewer into the heart of the painting. Despite their abstract nature, Pwerle’s works are grounded in a profound understanding of the natural world and the spiritual forces that shape it.

Minnie Pwerle, Awelye (Body Painting) A6220, 2005. Mitchell Fine Art.

Minnie Pwerle’s contributions to the world of contemporary art are immeasurable. Through her vibrant and expressive paintings, she not only celebrated the rich cultural heritage of her people, but also offered a glimpse into the timeless beauty and wisdom of Aboriginal spirituality.

Despite a very short career, Pwerle was able to impose herself as one of the most prominent Australian Aboriginal artists, and her works were quickly added to major public collections such as the Art Gallery of NSW, Art Gallery of South Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and Queensland Art Gallery. Internationally, the artist was included in a 2009 exhibition of Indigenous Australian painting at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and sold internationally to museums, institutions, and private collectors.

Regarded as one of Australia’s leading contemporary woman artists, Minnie Pwerle’s legacy continues to inspire artists and audiences alike, reminding us of the power of art to transcend boundaries and connect us to something greater than ourselves.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!