Summary

- Miné Okubo was an American artist born in California in 1912 to Japanese parents. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Okubo, like other Japanese Americans, was forced to leave her home and go through different processing centers.

- Okubo started recording life in the relocation camps. Her drawings were to form a book called Citizen 13660–the number of the family unit she was assigned to.

- Her drawings depict racism, isolation, and everyday life in the difficult camp conditions.

- Citizen 13660 became a primary source of the Japanese American experience in the internment camps.

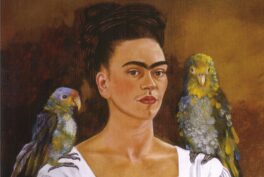

Front cover of Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo, 1946. Published by University of Washington (Revised Edition) in 2014. Amazon.

Early days

Miné Okubo was born in Riverside, California, in 1912 to Japanese parents who immigrated to the United States in 1904 when they represented their home country in the St. Louis Exposition of Arts and Crafts. Okubo’s mother was a calligrapher who graduated with honors from the Tokyo Art School, and her father was a scholar. In America, her mother raised their seven children, and her father worked as a gardener.

Life across the Pacific Ocean was poignant. For Okubo, it was also a lesson learned as she saw how her mother struggled as both a homemaker and an artist:

Oh, I knew I was never going to get married. Look at my poor mother. Her life was ruined working so hard for the children. She never had time to do anything. She stopped painting. I wasn’t going to wash anybody’s socks, cook their dinner. Forget it!

Citizen 13660

Photograph of Miné Okubo, 1946, Gift of Miné Okubo Estate, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Museum’s website.

The young artist attended the University of California, Berkeley, where she earned her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees. In 1938, as the Bertha Taussig Traveling Art Fellowship recipient, she won the chance to study art in Europe. It could have been a two-year opportunity if war did not break out a year later.

Okubo was stuck in Switzerland with no way to get home. It took a while, but she eventually made it to New York only to learn that her mother had passed away. She returned to the California Bay Area afterward, where she worked as part of the New Deal’s Federal Art Project, creating mosaics and frescos alongside artist Diego Rivera. Her works during that time would be exhibited as part of the San Francisco Art Association.

Executive Order 9066

Pearl Harbor was under attack on December 7, 1941, thrusting the United States into the war. In response to the incident, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, a document that would send thousands of Japanese Americans to internment camps located in the western United States.

In a matter of days, families were forced to pack, make government arrangements for their homes, and figure out what to do with the possessions they could not take with them. One of Okubo’s brothers joined the U.S. Army whilst the rest of the family went to different processing centers. Thankfully, she at least was able to stay with one of her brothers (who she only referred to as “my brother” throughout her book). They were first sent to the registration center at Tanforan in San Bruno, California, where they stayed for six months and then transferred to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. She and her brother were assigned the family unit number 13660.

Citizen 13660

Okubo spent her time recording life at the camp: the indignities of sharing restrooms and living in squalid conditions, being at the mercy of the weather, as well as the absolute boredom and monotony they faced day after day. There were also brief moments of amusement, like talent shows and movie nights, or people experiencing snow for the first time. In the 1983 edition of the book, Okubo wrote:

In the camps, first at Tanforan and then at Topaz in Utah, I had the opportunity to study the human race from the cradle to the grave, and to see what happens to people when reduced to one status and condition. Cameras and photography were not permitted in the camps, so I recorded everything in sketches, drawings, and paintings. Citizen 13660 began as a special group of drawings made to tell the story of camp life for my many friends who faithfully sent letters and packages to let us know we were not forgotten. The illustrations were intended for exhibition purposes.

Citizen 13660, the 1983 edition.

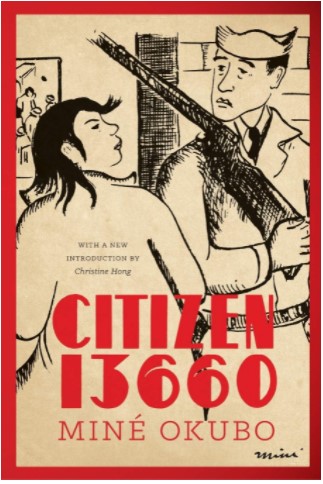

Added next to the lines of text were one-panel drawings. Okubo included herself in most scenes, serving as a kind of tour guide for us, the viewer. We see situations through her eyes and often her reactions. And we can feel how she was ostracized through one panel created shortly after Pearl Harbor before the Executive Order went into effect. This scene takes place on a public bus, with Okubo pondering as her fellow riders stare at her with furrowed brows. “The people looked at all of us, both citizens and aliens, with suspicion and mistrust,” she reminisced.

Miné Okubo, Receiving hostile looks while traveling by bus, Berkeley, California, 1941-42, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

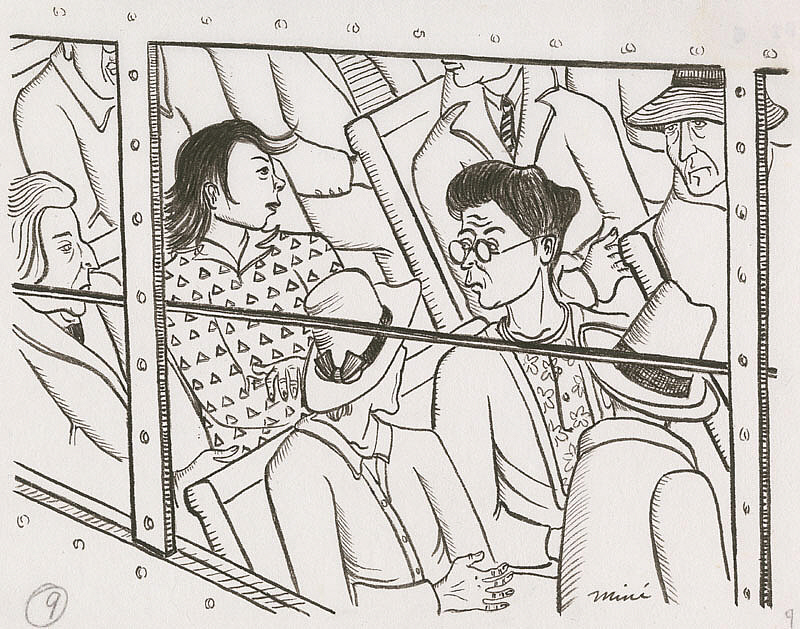

A plot twist confirmed the suspicion we shared with Okubo a few pages later: In another drawing, she and her brother look back at their “happy home” as they prepare to leave for the bus station that will take them to Tanforan. Okubo has tears running down her face.

These artistic productions connect the author with the reader beyond the actual historical event. In an introduction to the 2014 edition, Dr. Christine Hong identified an underlying message, asserting that Okubo is both a figure within the panels and a constant reminder that “this could be you.”

Miné Okubo, Miné and Benji depart from their home, Berkeley, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Citizen 13660: Tanforan

The Tanforan Assembly Center was the first stop in this journey away from home. Only weeks prior, Tanforan stood for Tanforan Park Racetrack. Upon Okubo’s arrival, horse stables had become housing for entire families. Meanwhile, mess halls and other facilities were repurposed from buildings or erected from the ground up.

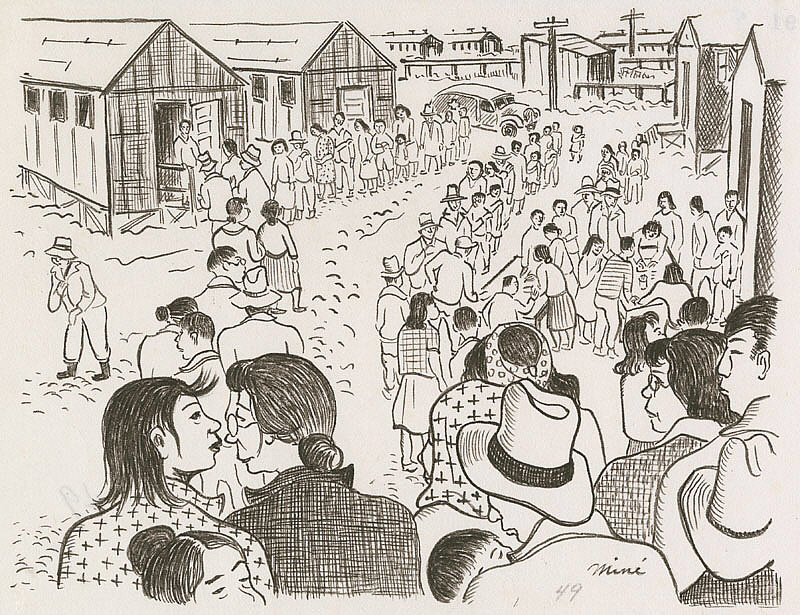

Many of Okubo’s scenes about Tanforan show seemingly unending lines and crowds. She filled these pages with lines to get vaccinated and lines to get into the post office, crowds in the mess hall, and crowds looking for their baggage. It must have been overwhelming and exhausting.

Miné Okubo, Waiting in line to receive vaccinations, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

After arriving at Tanforan, the siblings were separated and told to undress for smallpox under the supervision of a nurse. Next, they were ushered to the registration where she had to fight for her and her brother to remain together. And then, amongst looming bad weather, they trekked through the mud across the camp to the horse stables that were their designated living space.

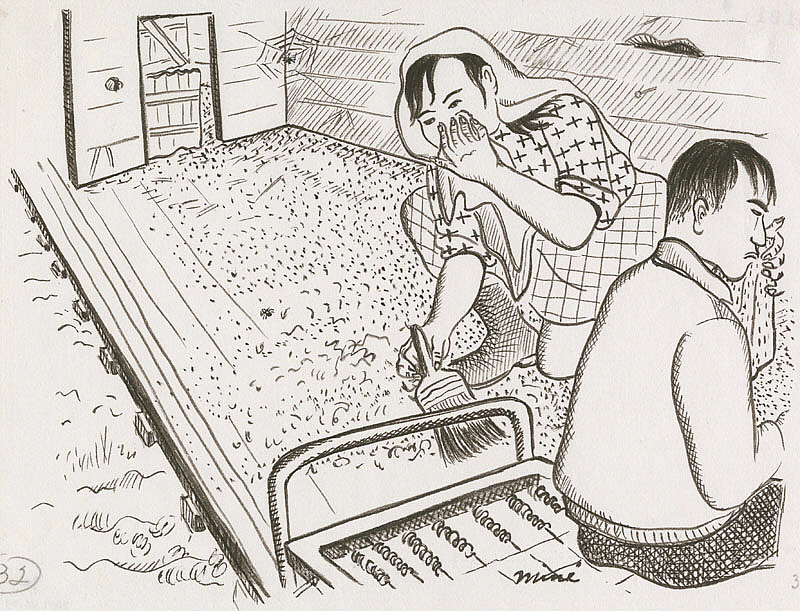

Okubo depicted her and her brother sweeping out the stall by hand with a whisk broom. She wrote:

The guide left us at the door of Stall 50. We walked in and dropped our things inside the entrance. The place was in semidarkness; light barely came through the dirty window on either side of the entrance. A swinging half-door divided the 20 by 9 ft. stall into two rooms. The roof sloped down from a height of twelve feet in the rear room to seven feet in the front room; below the rafters an open space extended the full length of the stable. The rear room had housed the horse and the front room the fodder. Both rooms showed signs of a hired white-washing. Spider webs, horse hair, and hay had been whitewashed with the walls. Huge spikes and nails stuck out all over the walls. A two-inch layer of dust covered the floor, but on removing it we discovered that linoleum the color of redwood had been placed over the rough manure-covered boards.

Citizen 13660

Miné Okubo, Miné and Benji sweep the stall, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

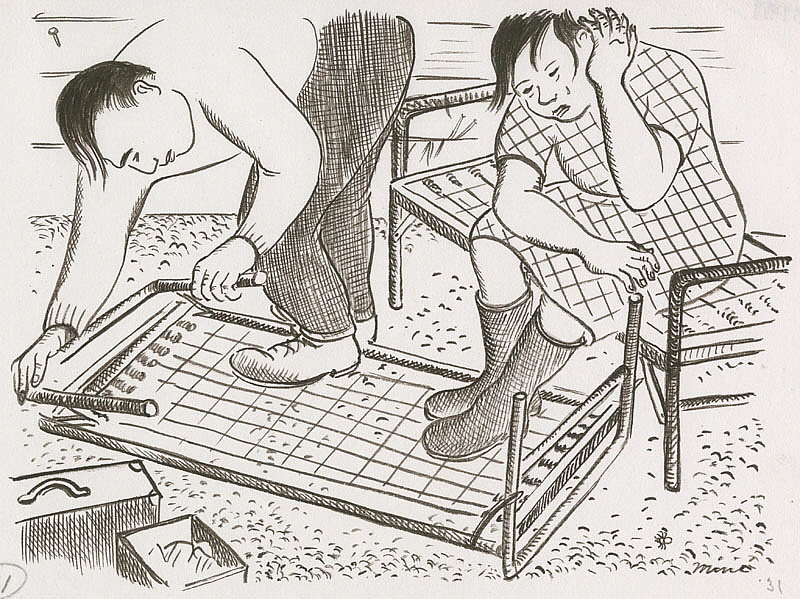

She also drew them setting up their cots:

We opened the folded spring cots lying on the floor of the rear room and sat on them in the semidarkness. We heard someone crying in the next stall.

Citizen 13660

Miné Okubo, Miné and Benji assemble cots, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

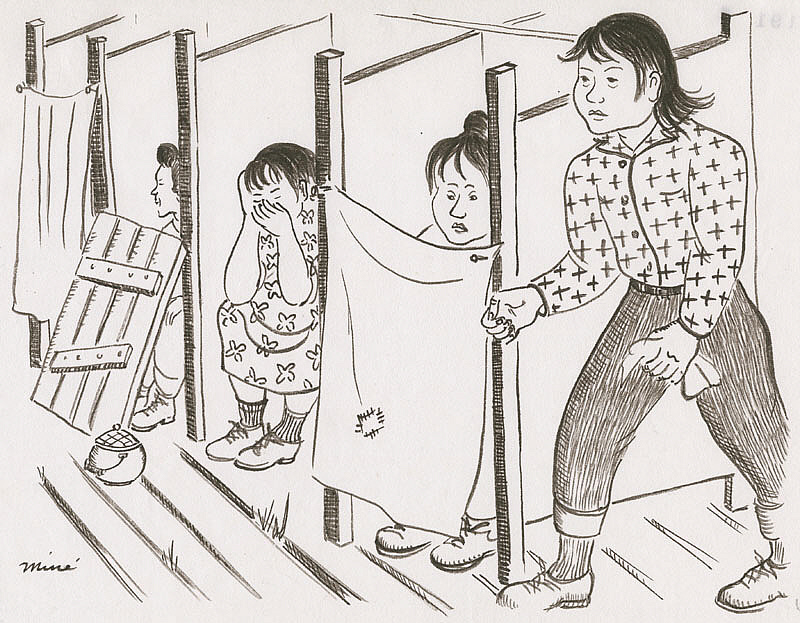

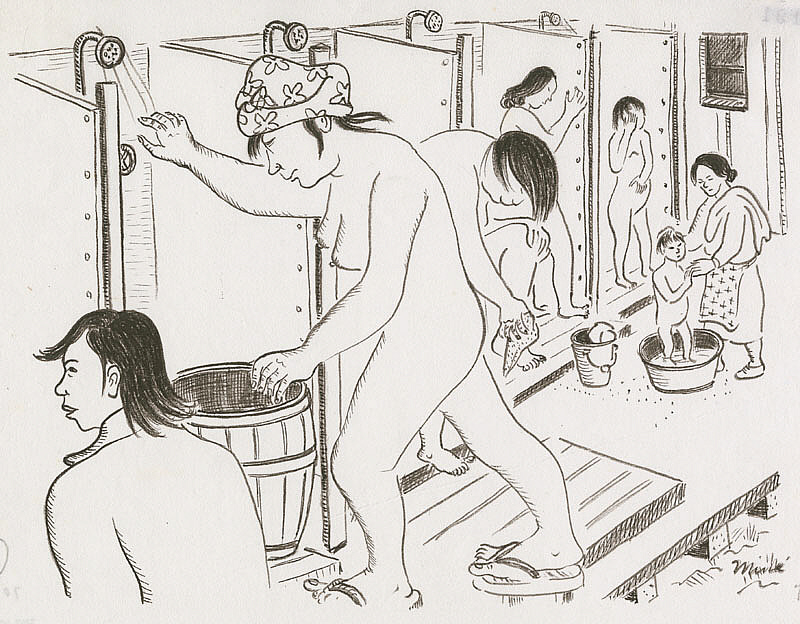

She showed women using communal bathroom stalls and showers. Without any privacy afforded to them, they utilized what they could: old blankets nailed up and boards that leaned against their knees. The showers also offered little modesty.

Miné Okubo, Community toilets, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Miné Okubo, Community showering, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

In a particularly poignant scene, Okubo wrote:

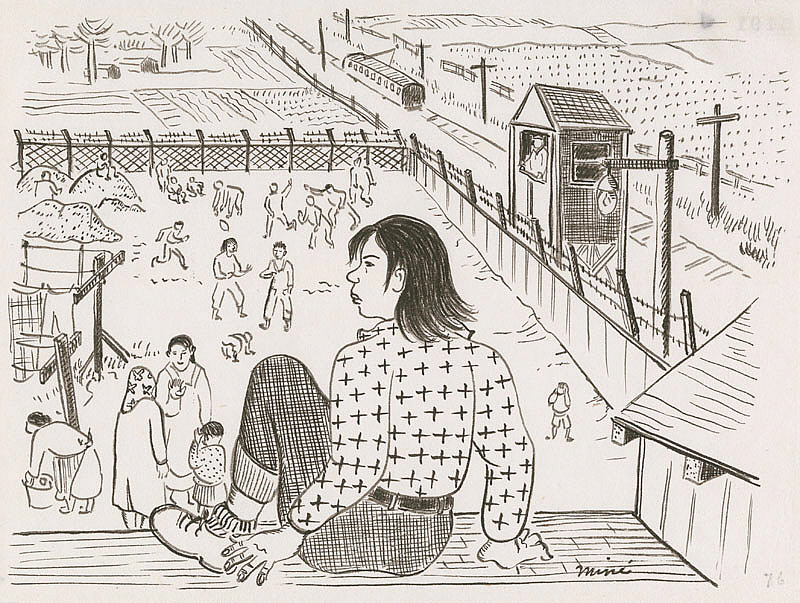

We were close to freedom and yet far from it. The San Bruno streetcar line bordered the camp on the east and the main state highway on the south. Streams of cars passed by all day. Guard towers and barbed wire surrounded the entire center. Guards were on duty night and day.

Citizen 13660

She shows herself sitting on the roof overlooking the camp with a streetcar just on the other side of the fence with the guard tower and barbed wire between them.

Miné Okubo, Observing camp activities from a rooftop, Tanforan Assembly Center, San Bruno, California, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Citizen 13660: Topaz

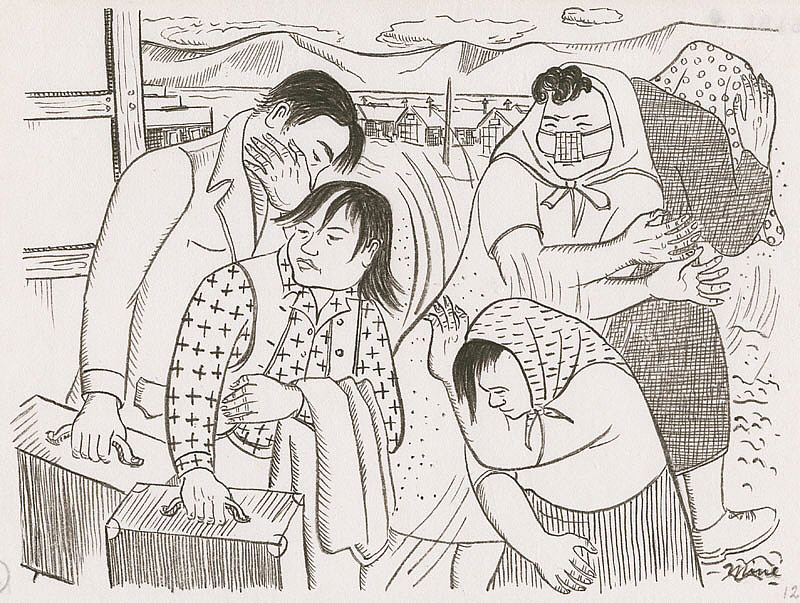

September brought the relocation to Topaz in Utah on a two-day train trip. This was the more permanent location—though it was unknown how permanent it might be, and the camp was still in the midst of construction. They saw some familiar faces from Tanforan, who helped Okubo and her brother find their living space. Getting there was unpleasant as the wind, sand, and dust blew into their faces.

Miné Okubo, Miné and Benji are escorted to their barrack, Central UtahRelocation Project, Topza, Utah, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

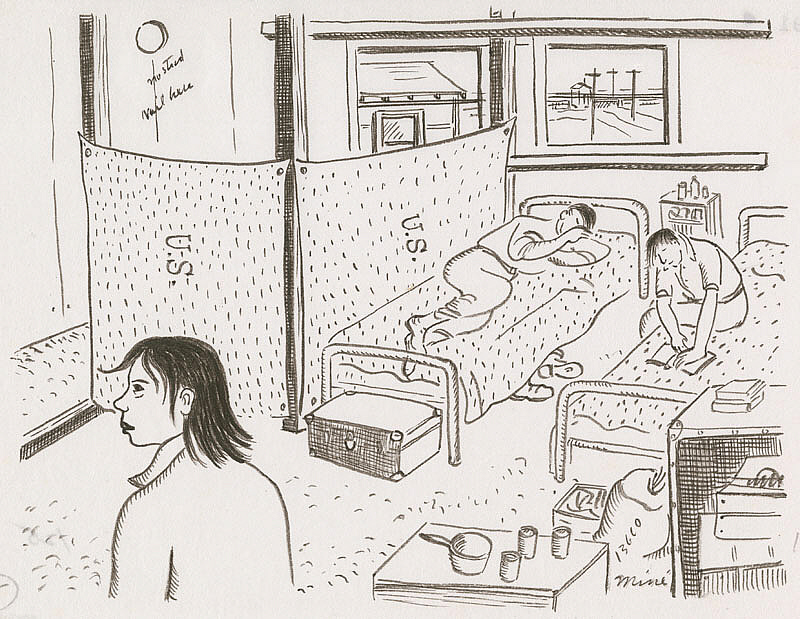

Okubo and her brother had to live with a stranger, a young man who hoped to relocate shortly with his father. They hung up a rare spare blanket to create a private space for Okubo, the lone woman.

Miné Okubo, Interior of Mine and Benji’s barrack, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

She resumed her sketching: the community restrooms and bathing facilities (“four tiny bathtubs”), the crowded mess halls, and the schools where she taught art. She even documented the annoying fact that they tended to wear the same clothes as they all had to order from the same mail-order catalog. The expressions of the women, in their matching shirts, are at once humorous and heartbreaking.

Miné Okubo, Clothing styles at camp, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942-1944, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Okubo and other forcibly displaced Japanese-Americans continually battled the weather–extreme heat and cold, blustery sand and dust storms, and constant rain ensued by brutal mosquitos in the summertime. Cattle, chickens, and hogs were brought in, and people planted gardens that everyone helped out with, though the climate and soil made it hard for the produce to thrive.

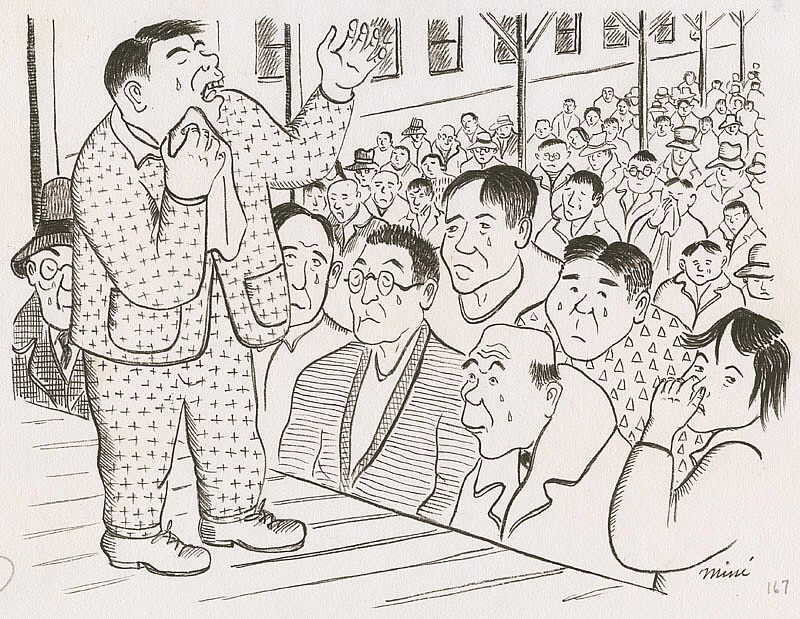

In early 1943, the military created a combat unit of Japanese Americans. Roosevelt sent officials to the internment camps and asked for male volunteers. They had to complete a complex questionnaire intended to prove not only their loyalty to the United States but also their opposition to Japan. Many, unsurprisingly, found this insulting, which added to the existing tension. Those who answered that they wanted to return to Japan were segregated and later sent to a separate camp.

Miné Okubo, Meeting to discuss military recruitment, Central Utah Relocation Center, Topaz, Utah, 1942-1944, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Rules began to relax slightly and passes were distributed for inmates for work or shop for basic necessities. Eventually, this gave rise to a complicated relocation reversal process. People returned to their previous lives or got new jobs or, like Okubo’s brother, joined the military.

Much red tape was involved, with ‘relocatees’ checked and double checked and rechecked. Citizens were asked to swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and to defend it faithfully from all foreign powers. Aliens were asked to swear to abide by the laws of the United States and to do nothing to interfere with the war effort. Jobs were checked by the War Relocation offices and even the place of destination was investigated before an evacuee left.

Citizen 13660

Okubo left in January 1944:

I was now free.

Citizen 13660

The last page shows Okubo as she looked back at those who remained:

I relived momentarily the sorrows and the boys of my whole evacuation experience, until the barracks faded away into the distance. There was only the desert now. My thoughts shifted from the past to the future.

Citizen 13660

Miné Okubo, Boarding the bus to leave camp, Central Utah Relocation Project, Topaz, Utah, 1942-1944, Japanese American National Museum, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Afterwards

Published in 1946, Citizen 13660 was the first of its kind as a primary source of the Japanese American experience in an internment camp.

In 1976, Executive Order 9066 was officially repealed by President Gerald Ford. Five years later, Okubo testified before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. She shared her story, providing copies of Citizen 13660, the degradation she felt as a loyal American forced into a camp, and the hope that such a thing never happened again.

In 1988, more than 40 years after the end of World War II, the US Congress issued a formal apology and provided reparations to those who had been interned.

Though she is best known for Citizen 13660, Okubo was a prolific artist who painted until her death in 2001. In a book on her work, author Elena Tajima Creef described walking into Okubo’s New York apartment and seeing works in a range of sizes in various mediums and styles on every available surface.

The Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles is home to the Miné Okubo Collection. In 2021 (and ending February 20, 2022), the museum commemorated the 75th anniversary of her book, Miné Okubo’s Masterpiece: The Art of Citizen 13660, featuring her original drawings and drafts. Living on the East Coast, I was not able to see the exhibition in person. However, the museum’s website has some wonderful videos that discuss Okubo, as well as an online catalog of her work.