Nun, Scientist, Artist, Saint: Meet Hildegard von Bingen

Saint Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), also known as the Sybil of the Rhine, is one of the most renowned figures from the European Middle Ages. She...

Iolanda Munck 18 July 2024

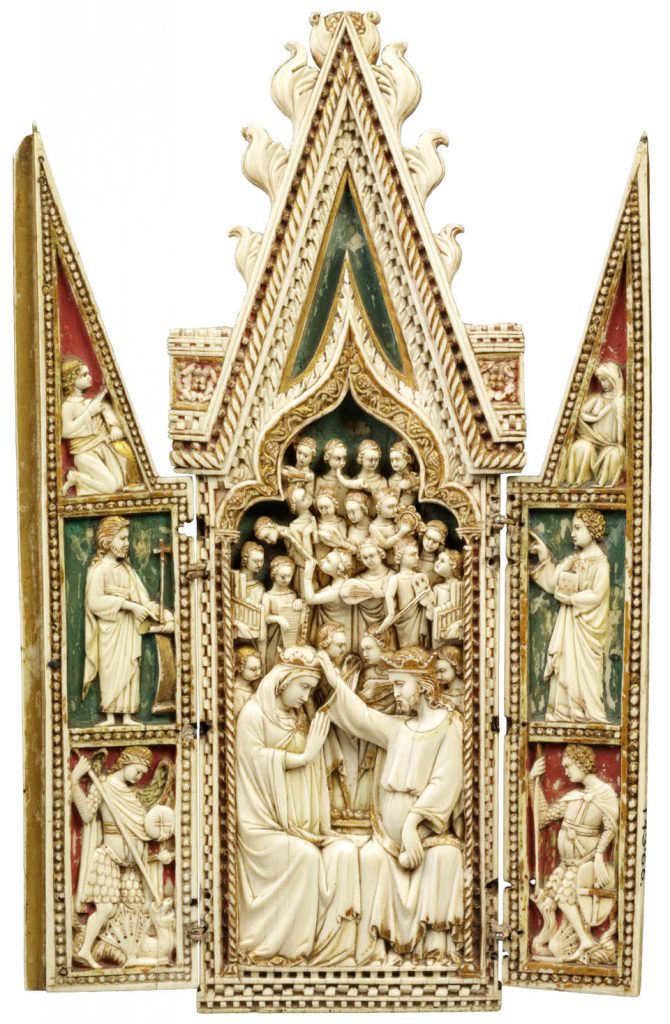

For devoted Christians, a portable shrine provided an immediate and intimate way to connect to a higher power within a monastic space or the privacy of one’s home. Portable shrines were small-scale, ritual objects with movable parts that could be folded up and easily transported. Popular in medieval Christian Europe, these holy artifacts were tangible treasures that provided a sacred space for worship.

In medieval Christian art, a portable shrine was a sacred object often inspired by an actual place of worship, be it a basilica or a church. They functioned as part of Christian religious practice outside of the church. Portable shrines served as a gateway for Christians to communicate with the Divine or pay devotion to a particular saint, Christ, or the Virgin Mother Mary.

They were usually small in scale so they could be easily transported. Shrines could be touched and handled, a special privilege for the faithful, that they believed brought them closer to the holy realm. When closed, a portable shrine resembled an ordinary box or in some cases, a statue or doll-type figure. When opened, an entire world unfolded before your very eyes that changed everything.

Portable shrines were often made of wood, then gilded with copper, silver, or even gold enamel work. Ivory was also a popular material in medieval Europe, especially in the use of religious art. Portable shrines, altars, tabernacles, and statues were all carved from this heavenly material. Carved ivory reliefs brought to life Christian religious iconography and created a visual narrative for devotees.

Portable shrines were also lavishly decorated with precious and semi-precious gemstones around the framework. In medieval times, many people believed that certain gemstones possessed healing powers or protected them from evil. This belief tied an even deeper meaning to the types of gemstones included in the shrine.

Most portable shrines consisted of two panels or more. Shrines unfolded to reveal two parts (diptych), three parts (triptych), or more than three parts (polyptych). The main focus of each shrine was depicted on the central panel; a revered saint, Jesus, the Virgin Mary (alone or with child), or in some cases, an important scene from the Bible was represented. The two outside panels or ‘’wings’’ were often reserved for angels, apostles, or disciples.

When folded closed, these shrines took on another form. Some transformed into statues, books, or boxes. Their ordinary, outside appearance harbored a hidden world within; a world that connected the pious to the holy.

Many different types of portable shrines were created in medieval Europe that enriched the Christian religious experience. Other types of shrines also served as reliquaries, containers for sacred relics of Christian saints. Although portable shrines varied in shape and design, they all shared the same purpose – they opened a passage between Heaven and Earth.

Shrine Madonnas (vierges overantes/opening virgin) were unfolding statues that represented the Virgin Mary. These shrines originated in women’s monasteries and the first Shrine Madonna dates back to around 1200, from a nunnery in Boubon, France.

When opened, the interior revealed a spiritual world that often depicted the Holy Trinity and scenes from the Bible. These shrines were devotional objects placed upon altars in monasteries or displayed in private homes of wealthy Christians. Shrine Madonnas were often kept at remote or secret places and this helped to protect them from being stolen or destroyed. During the late Middle Ages, some Christian leaders had strong reactions towards the shrines that threatened their existence.

Shrine Madonnas varied in size; those that were intended for personal use were usually small, while those found in a religious community ranged from life-size to monumental in scale. Although the majority of Shrine Madonnas were produced in France, they were also created in Spain and Germany. On special occasions, these shrines were opened to strengthen and support prayer. When closed, these shrines morphed into doll-like statues that concealed a holy secret within their bodies. When opened, Shrine Madonnas displayed a portal to a heavenly world where believers could access the Divine. Being able to touch, hold, open and close these sacred objects must have felt incredibly special for the faithful.

Book shrines, also known as cumdach (in old Irish), were not actually books, just made to look like one. These shrines were found primarily in medieval Ireland. They were elaborately decorated boxes that held sacred Christian relics or holy manuscripts. Book shrines were often made of wood but heavily decorated with precious metalwork or ivory carvings. They were also adorned with semi-precious gemstones or rock crystals and depicted the symbol of the cross on the outside ‘’cover’’ or face. An inscription could be found either on plaques that ran along the border or elsewhere and a chain or rope was attached to the shrine. Most book shrines were small in size as they were meant to be worn around the neck similar to a talisman to ward off evil and protect the wearer.

Bell shrines resembled the shape of a bell and were used to enshrine a hand bell from an important religious Christian site or one that belonged to an important leader of the church. These liturgical objects were equally as elaborate as book shrines, decorated with jewels and engraved with Celtic patterns. They also had an attached strap, but with the purpose of being suspended within a space. Bell shrines were sometimes found at holy pilgrimage sites where pilgrims could touch and pray to the relic.

Medieval portable shrines were powerful, sensory objects that were a physical representation of the spiritual. They gave Christians a corporeal means that intensified and strengthened their connection to the Divine. Their exceptional presence alone must have deeply inspired the faithful as their precious value alone was priceless.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!