Nun, Scientist, Artist, Saint: Meet Hildegard von Bingen

Saint Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), also known as the Sybil of the Rhine, is one of the most renowned figures from the European Middle Ages. She...

Iolanda Munck 18 July 2024

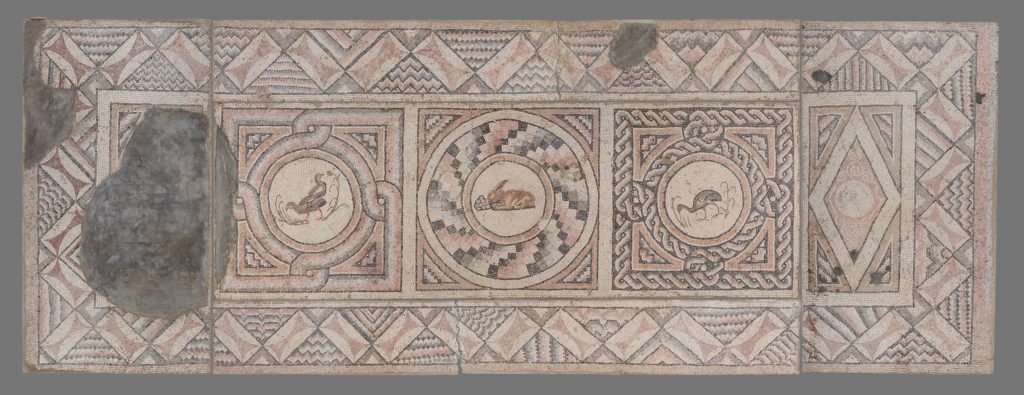

Welcome to the sparkling world of medieval mosaics! Although not as famous as illuminated manuscripts or stained glass, the mosaic was a popular art form that enlivened both Christian churches and Islamic mosques during the Middle Ages.

Mosaics are images made from little pieces of colored stone or glass, called tesserae. They most frequently decorate architectural settings. This ancient technique was popular in classical Rome but reached new heights during the Middle Ages. While Roman mosaics typically used stone tesserae in muted colors, medieval mosaics glitter thanks to brightly-colored glass and gold tesserae. Imagine how they would have sparkled during candlelit church services! In the classical world, mosaics were primarily floor decorations, but medieval artists covered the walls and ceilings with them instead.

Mosaics flourished as Christianity grew and prospered starting in the 5th century CE when they replaced murals as church decoration. This tradition took hold particularly strongly in the Byzantine Empire, especially in Turkey and Greece, and in Byzantine-influenced Italy. By contrast, the art form never really caught on in Western European nations like France and England.

Unsurprisingly, religious themes dominate the subject matter of medieval mosaics in the Christian world. The most important – usually those located in and near the apse, as well as on domed ceilings – feature monumental images such as Christ Pantocrator, the Virgin and Child, the Lamb of God (a symbolic representation of Christ as a lamb with a cross), and crosses. Elsewhere might appear representations of saints, especially the saint to whom a church is dedicated, angels, and biblical stories.

Art historians refer to narrative church decoration as “Bibles of the Poor,” since it taught Bible stories to illiterate congregations. Clear and legible medieval mosaics seem at first to fit this description perfectly. Yet upon further investigation, they actually contain a surprising degree of theological depth and often present their main themes symbolically. It’s unclear to us today how different categories of medieval viewers would have understood them.

However, not all medieval mosaics contained religious imagery. Figures of donors, especially clerical or royal patrons, appear frequently. One example of this is the famous pair of 6th-century mosaics depicting the Byzantine Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodore in the apse of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. Decorative patterned mosaics also cover columns, arches, walls, and more.

Early Christian buildings like Santa Pudenziana in Rome (4th century CE) and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna (5th century CE) contain naturalistic and complex mosaics derived from ancient Roman precedents, such as murals and manuscript illustrations.

Eventually, medieval art shifted in style, becoming less naturalistic than its classical precedents. This pared-down style attracts a lot of people to medieval art today. Medieval mosaics present no exception. Their simplified, decorative forms tell stories through line and color, rather than volume and shading. Human figures and faces appear rather generalized, sometimes to the point that mosaic name labels must be included to identify them. Backgrounds tend towards solid gold fields or non-specific landscapes. These scenes could take place anywhere and at any time. Large, boldly-gesturing figures, like those of modern-day comic strip characters, are easily legible to viewers in the church far below.

Although some medieval mosaics can appear flat and static, fine examples, such as those at the Greek monasteries of Daphni and Hosios Loukas or at Monreale Cathedral in Sicily, achieve grace and harmony in their monumental simplicity.

The Islamic world also abounds in medieval mosaics, which appear in both mosques and secular palaces. Following Islamic principles, mosaics in mosques are not figurative; they feature decorative patterns based on plants, architecture, or geometry instead of people and animals. However, Islamic mosaics are every bit as lovely and glittery as their Christian counterparts. They deserve an article on themselves. Fortunately, we’re already got one!

The surviving medieval mosaics we see today don’t necessarily appear the way they did in the Middle Ages. In fact, they were occasionally adapted by removing some of the tesserae and re-setting them in different designs to accommodate changing tastes and political regimes.

In the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna presents a good example. The Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great (454-526 CE), who commissioned some of the mosaics, practiced a form of Christianity called Arianism. After Arianism fell quite seriously out of favor, later leaders removed images of Theodoric and his court by altering the mosaic to show sets of curtains where each figure had been.

The generic faces of figures inhabiting many mosaic programs made it easy to erase images of your rivals. You didn’t even have to change the face necessarily, though you could. Simply modifying the inscription identifying the figure would also do the trick. At Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, remarried members of the imperial family sometimes replaced old spouses with new ones.

Although common wear and tear don’t really threaten medieval mosaics, moisture and earthquakes both do so significantly. As a result, many buildings’ mosaics have been destroyed or damaged. Some, like those at Charlemagne’s Palatine Chapel in Aachen, Germany, have since been reconstructed. But human intervention has more often harmed mosaics than helped them, mainly due to iconoclasm.

In the 8th and 9th centuries CE, Byzantine rulers outlawed the creation or veneration of religious images due to fears of idolatry. This ruling caused the destruction of countless mosaics, icons, and other Christian artworks in a practice known as iconoclasm. A contentious issue even at the time, iconoclast laws were overturned in 843 CE.

The medieval mosaics at Hagia Sophia in Constantinople are some of the most celebrated in the world. However, since Hagia Sophia was converted once again into a mosque in 2020, these Christian images have been hidden behind curtains. But don’t let that stop you from learning about them here. All the other mosaics mentioned in this post, on the other hand, are ordinarily accessible to the public. The best place to see medieval mosaics today is probably the myriad early Christian basilicas of Ravenna, Italy.

Richard Bowen, Beth Harris, and Steven Zucker. “Mosaics, Santa Prassede (Praxedes), Rome,” in Smarthistory, December 3, 2015. Accessed April 13, 2021.

Penelope Davies, et al. Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition. NJ: Pearson Education, 2007. P. 245-260, 268-272.

Allen Farber. “San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015. Accessed April 13, 2021.

Beth Harris, and Steven Zucker. “Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (Italy),” in Smarthistory, December 10, 2015. Accessed April 13, 2021.

Beth Harris, and Steven Zucker.”Saint Mark’s Basilica, Venice,” in Smarthistory, December 15, 2015. Accessed April 13, 2021.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!