Rachel Ruysch in 5 Paintings

Rachel Ruysch was a Dutch still-life artist renowned for her elaborate and lifelike floral paintings. Her talent earned her a position as a court...

Nikolina Konjevod, 3 June 2025

Judith Leyster was a highly regarded genre painter in 17th-century Holland. Her career was cut short by her marriage, and after her death, her pictures were forgotten, ignored, or sold as works by male artists. She is now finally getting the recognition she deserves as a “lode (lead) star” – her own pun on her name – of the Dutch Golden Age.

Judith Leyster (1609–1660) was unusual, not just as a female painter, but as one who did not come from an artistic background. Her father was a successful brewer and cloth maker in Haarlem, Holland, who changed the family name to that of his business: Leyster (Lodestar). He probably encouraged his daughter towards a career in art after he went bankrupt in 1624, as a means of earning the family some much needed money.

Leyster trained with Frans Pieter de Grebber, a local portraitist and landscape painter, whose daughter and son were also learning in their father’s studio. Little is known about her early works, although she was enthusiastically mentioned in Samuel Ampzing’s guide to Haarlem in 1628 as having “keen and good insight.”

Judith Leyster, The Jolly Toper or A Fool Holding a Jug, 1629, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Her first known works, The Serenade and The Jolly Toper, date from 1629. At that time, the Haarlem art scene was dominated by the Hals brothers: Frans, famous for his freely painted, casually posed portraits, and his brother Dirck, who was a successful painter of humorous genre scenes. Leyster was clearly influenced by both.

The Jolly Toper has a plain grey background which works with the diagonal of the table to create an angled space for the leaning figure. The laughing mood and dynamic pose as the man raises the jug are very reminiscent of Frans Hals’ works like The Merry Drinker (1628–1630), although Leyster employs a more finished style. The figure’s ruddy cheeks, extravagant feathered hat, and loose costume mark him out as a figure from theatrical comedy rather than real life. And although he is a smoker and a drinker, the viewer is encouraged to laugh with him and enjoy his pleasures, rather than moralize about his vices.

Frans Hals, The Merry Drinker, 1628–1630, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

By 1635, Leyster had become one of the first women allowed into the Guild of St Luke, the artists’ association in Haarlem. She had her own studio and students, and well enough known to sign her works with a monogram, J-L*. Her 1630 Self Portrait, probably her presentation piece for the Guild, shows her as a confident master of her art with paint brushes and palette in her hands.

The portrait is a deliberately staged image. She is dressed far too formally to be actually working. Equally, she made the decision to change the painting on the easel from a portrait to one of her characteristic genre pieces, effectively advertising what she did best. The pose is casual: her open mouth almost suggests she is engaging the viewer in conversation. The loose painting of the oversized ruff and cap creates a sense of liveliness and movement as if she is in the act of turning toward us. Leyster’s direct gaze and dynamic pose is a defiant statement that she can and will compete in a male world.

Judith Leyster, Self Portrait, c. 1630, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, USA.

The Utrecht Caravaggisti were a group of Dutch artists influenced by the work of Italian painter Caravaggio, who exploited dramatic light and shade contrasts and naturalistic compositions. It is possible that Leyster came into contact with their work while her family briefly lived near Utrecht around 1624, although more likely she knew of them through examples in Haarlem. Certainly she was one of the first painters in Haarlem to explore the possibilities of candlelight.

A Game of Tric-Trac (c. 1631) shows three figures gathered round a table lit by a single lamp. The shadowy background and the inward-leaning poses create a sense of intimacy and engagement. The flame picks out surprisingly bright colors and lively facial expressions, which capture a moment in time. The angled table and the strong compositional diagonals, seen especially in the foreground figure, are exaggerated by an unusual viewpoint as we seem to look down on the scene.

Judith Leyster, A Game of Tric-Trac, c. 1631, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA, USA.

There is documentary evidence that Leyster and Frans Hals knew each other and were rivals in Haarlem. Leyster was a witness at the christening of one of Hals’ children and they were involved in a legal dispute over a student in 1635. The similarity in their work has also led some art historians to suggest that Leyster may have trained with Hals. Even during her own lifetime, Leyster’s work was being mistaken for, or deliberately presented as, Hals’ and it was this which led to her effectively being “erased” from history.

In 1892, a lawsuit over the sale of an alleged Frans Hals painting led to the discovery by Dutch art historian, Hofstede de Groot, that the distinctive J-L* monogram on The Serenade and five other pictures was actually Leyster’s. It was the start of her rediscovery. Other works by Hals, and by Leyster’s husband Jan Miense Molenaer, were examined and around 20 paintings are now attributed to her.

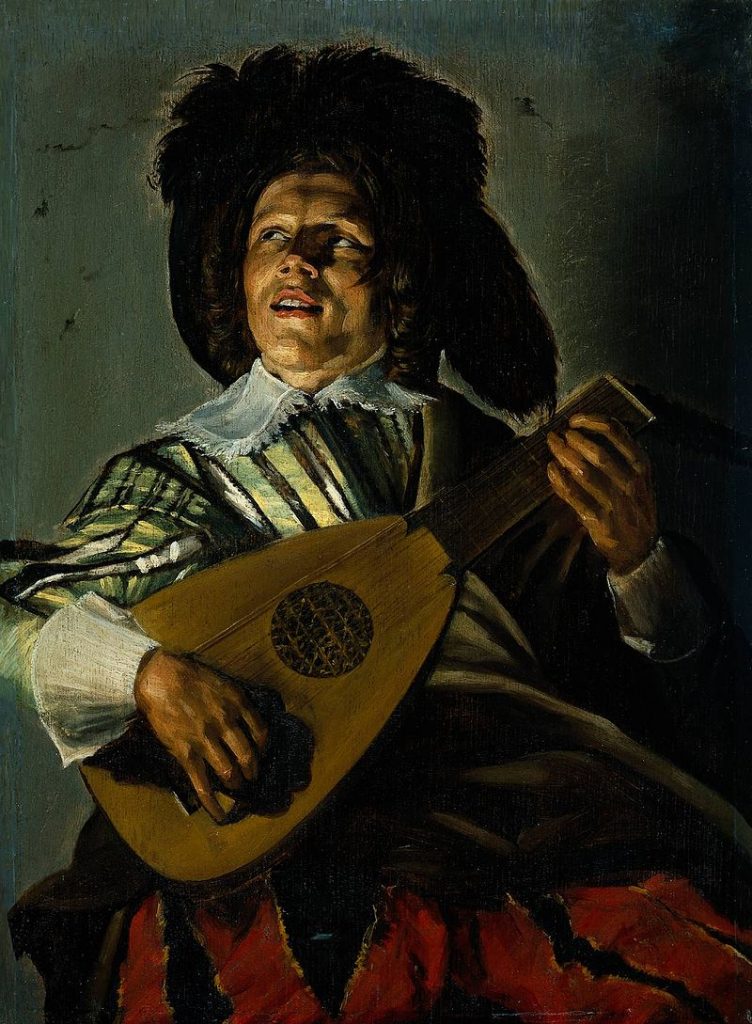

Judith Leyster, The Serenade, 1629, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

The Serenade shows how Leyster effectively combined the dramatic lighting of the Utrecht Caravaggisti with the less finished style of Frans Hals. Her use of backlighting to create a halo-effect around the lute-player’s elaborate hat was unusual, allowing her to create deep areas of shadow and giving him a theatrical appearance. Like many of her works, it is an action pose: the man seems to be caught open-mouthed in mid-song. He is looking to the side, perhaps directing his gaze to the woman he is serenading, perhaps out from the stage to an unseen audience. The sense of immediacy is emphasized by strong strokes of loose brushwork, especially on the fingers and face.

Judith Leyster, The Proposition, 1631, Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands.

It is tempting to dismiss Judith Leyster as a “female Frans Hals,” but she has her own distinctive style which derives partly from her exploitation of Caravaggisti light and composition, but also from her perspective on women. Her own self portrait is a prime example of this. At a time when women were expected to be quiet and respectable, she shows herself as exuberant and extrovert, confident in her own abilities.

Her painting The Proposition (1631) shows a very typical genre scene of a woman receiving the attention of a suitor. However, whereas most male representations focus on the loose morals of the woman, or the bawdy humor of the encounter, Leyster makes clear that this is unwelcome attention. The light captures the glint of coins in the man’s hand, the leering expression, the intrusive hand on the female figure’s arm. She continues to sew with a quiet, calm determination. The blue and white outfit seems a deliberate Virgin-like choice of costume, and Leyster employs back lighting to give the hint of a halo around her head. There is an almost Vermeer-like serenity and introspection about her.

Jan Miense Molenaer, A Woman Playing the Virginal, c.1637, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

In 1636, Leyster married Jan Miense Molenaer (1610–1668), a fellow Haarlem artist. The couple moved to Amsterdam where Molenaer continued his successful career as a painter of genre groups. Leyster did not carry on painting. She had five children, only two of whom survived into adulthood. There was a household to run, especially after 1648 when the couple bought a country manor in Heemstede, outside Haarlem. Equally, having grown up in a family business, she now took charge of Molenaer’s finances and acted as an art dealer for her husband’s work.

It also seems likely that she helped out in his studio. There are a number of works like A Woman Playing the Virginal (c. 1637) in which Leyster is thought to have posed. The children are not hers, so this is not a family portrait but instead a genre allegory about love. Harmonious music was a well-established metaphor for romance. The chained monkey was a symbol Molenaer had used before to represent sexual restraint and the children represent the fruits of a happy marriage.

Judith Leyster, A Tulip (watercolor and silverpoint) from The Tulip Book, 1643, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, Netherlands.

Art historians are divided over whether Leyster felt compelled to give up painting professionally after her marriage, or whether she chose to. For some, she is a prime example of a woman forced to conform to the role of wife and mother at the expense of her talent. But she seems never to have been a prolific artist, and probably always saw painting as a profession rather than a vocation. She certainly continued to be actively involved in the art world. She may well have worked with her husband on paintings that were then sold as his. However, the only signed works which survive after her marriage are watercolor illustrations for a book about tulips dating from 1643.

There are only about 20 surviving works which are generally ascribed to Judith Leyster. Hers is a story of promise unfulfilled. But the few paintings which do survive show skill, vibrancy, an ability to render light and create mood, and a tremendous joie de vivre. Leyster breathed life and character into her figures through her loose, rapidly applied brushwork and her informal poses and compositions. She was genuinely revolutionary in her use of halo lighting. It is impossible to look at her best work and not wish that she had painted more. However, even what survives is more than enough to justify her place as a significant Dutch Golden Age painter. Not just a token woman, not just a female Frans Hals, but a lead-star in her own right.

Frima Fox Hofrichter, Judith Leyster, 1609–1660, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2009.

James Welu and Pieter Biesboer, Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and her World, Worcester Art Museum, 1993.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!