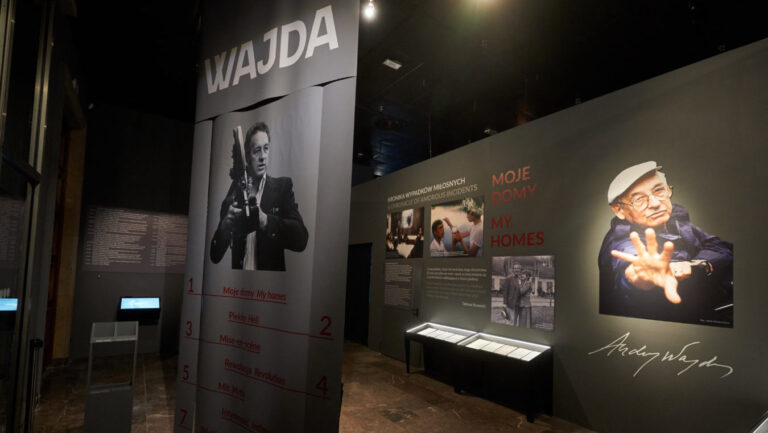

Ladies and Gentlemen, and now I will speak in Polish… – the famous words Polish director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) said while receiving an honorary Oscar in 2000 for a lifetime achievement crowned WAJDA, an exhibition revealing Wajda as a painter.

Andrzej Wajda is one of the most famous and respected Polish film directors and at the same time author of some screenplays of his films. In addition, he also used to be a painter and theater director. The number of his films is estimated at around 40, largely based on Polish history, literature and art, but also drawing from French tradition, e.g. Danton – for which he received the Louis Delluca award for the best French film in 1982, or Japanese one, like Nastazja (1994).

Hell

Andrzej Wajda began his career as a student of art painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków soon after World War II (from 1946), but quickly redirected his focus in favour of studying at the Film School in Łódź. His painterly sensitivity, however, left a clear mark on him. While working on his films, he drew each scene on a separate sheet of paper. During the exhibition, the wonderful visual aspect of Wajda’s films has been emphasized many times. For this reason, one of Andrzej Wróblewski’s (Wajda’s fellow mate) paintings from the war series Shooting has been hung here.

In addition to Wajda’s first steps in his film career, in this part of the exhibition presentations of one of his last films are presented, Katyń – reminding the shooting of 22,000 of Polish officers by the Soviet Army during World War II. Wajda felt it was his duty to make this film, mainly because his father died that way.

There are also stills from the film about the tragic Warsaw Uprising (1944), entitled Sewer from 1957. The film’s action takes place mainly in sewers, through which the insurgents tried to escape from captivity awaiting them in the face of the inevitable defeat of the uprising.

Mise-en-scène

In this most extensive part of the exhibition, we could admire the richness of literary and painting references in Wajda’s films, fragments of recordings that did not form part of the film, original costumes and scripts of never made productions.

Revolution

The movies about the class rebellion make a significant part of the exhibition. There were for the viewers to admire fragments and props from The Promised Land (among other presenting the situation of workers in a factory in the 19th century Łódź), the trilogy: Man of Marble, Man of Iron and Man of Hope – about workers’ fight for law in communist Poland, and from Danton, which presents the height of the French Revolution. This film was made in Polish-French co-production.

Myth

This part of the exhibition was devoted to key historical events about Poles which have been described in Polish fine literature and imprinted in Polish DNA. The most important films are Pan Tadeusz – based on the epic from the first half of the 19th century, telling about the Polish noble family against the background of the fight of Polish troops led by Napoleon during the war with Moscow (1812). Another is Ashes – a film adaptation of the book, which ends with the story of the defeat of Napoleon, and in this way Poles too. The third film is The Wedding – a film adaptation of the drama from the beginning of the 20th century, depicting a traditional Polish peasant wedding. Wajda used this as an excuse to show the colourful, Cracow folk costumes and customs of that era.

There’s a room dedicated to painting and literature analogies in Wajda’s scenes. There are paintings by such Polish artists as Jan Matejko, Aleksander Gierymski and Jacek Malczewski, as well as foreign one – Edward Hopper, and stills from Wajda’s films in which we can clearly see that the director was inspired by them.

Intimacy

Here we have films about more intimate, emotional themes with a large participation of women. There are also movies that Wajda made abroad, e.g. Nastazja in Japan, based on an excerpt from the book by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Idiot. Wajda’s interest in Japan is widely known – the director founded the Manggha Center of Japanese Art in Cracow.

(Im)mortality

In addition to films about illness, death, departure (including those inspired by Polish modernist stories, such as The Birch Wood, The Maids of Wilko), we can witness the climax of Wajda’s career as an extremely talented, fulfilled director. His final film, Afterimage (2016), is a comeback to the beginning of his career, telling the story of Władysław Strzemiński, a Polish painter and painting theoretician in 1950s Poland and influential teacher at the School of Fine Arts in Łódź. Afterimage makes evident that within the soul of this wonderful, insightful director lingered a memory of what had started his world career: painting.

The exhibition WAJDA was shown in the National Museum in Kraków, Poland. It will be exhibited in other European and Asian cities, with details yet to be determined.