Masterpiece Story: L.O.V.E. by Maurizio Cattelan

In the heart of Milan, steps away from the iconic Duomo, Piazza Affari hosts a provocative sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan. Titled...

Lisa Scalone 8 July 2024

9 June 2024 min Read

Known for his striking portraits of high-society figures, John Singer Sargent was one of the most successful painters of his day. But after causing a scandal in Paris with his infamous portrait, Madame X, Sargent left France and retreated to the English countryside, where he began working on a painting unlike any other. Here, we discuss his masterpiece from 1885-6, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose.

A wreath around her head

Around her head she wore

Carnation, lily, lily, rose

And in her hand a crook she bore

And sweets her breath compose.

Ye Shepherds Tell Me

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London, UK.

Inspired by a boating expedition on the Thames River, where he saw Chinese lanterns hanging from trees surrounded by lilies, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) began working on what would be considered one of his most enchanting compositions. Painted over two summers, in 1885 and 1886, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose depicts two young girls in a lush garden as they carefully light paper lanterns.

The scene is bathed in the light of dusk. Stepping into a clearing in the woods, we witness an intimate moment between two sisters unfold. A symphony of cotton dresses and paper lanterns among the glowing pinks and oranges of twilight. A botanical delight interlaced with the themes of childhood innocence and fleeting moments.

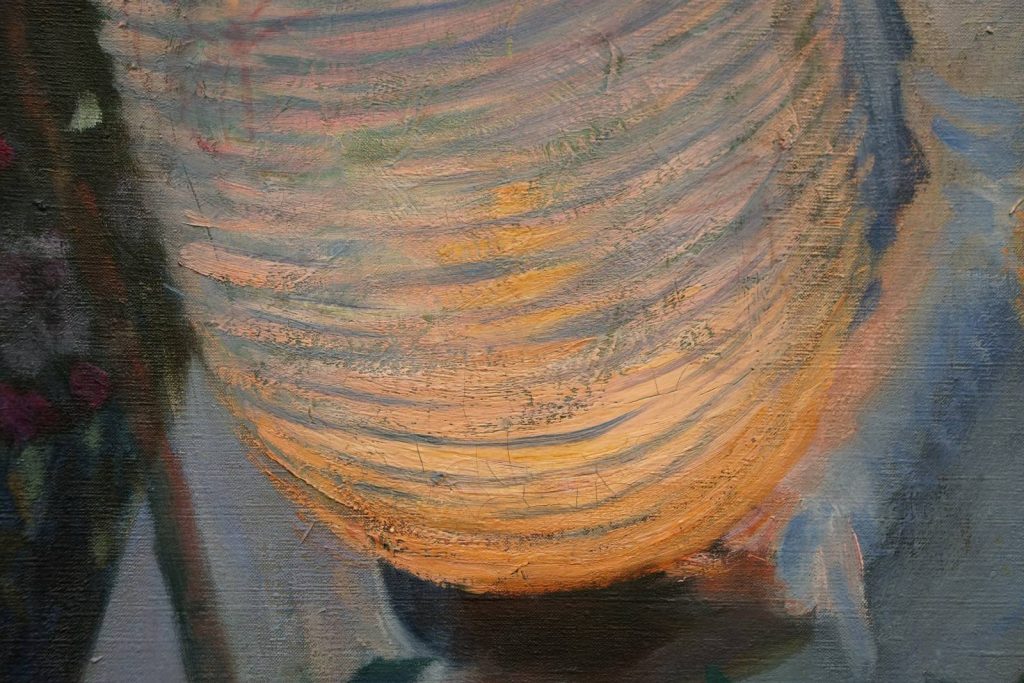

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Detail. Steven Zucker.

Sargent began creating the composition while staying at the home of artist Francis Davis Millet. Though he originally intended to paint Millet’s daughter, the subjects are the daughters of another of Sargent’s artist friends, Frederick Barnard. Sargent reportedly chose the young models for their hair—the exact color he was after. Dorothy, 11 years old, can be seen in profile, while Polly, 7, is facing toward us. Sargent’s gestural brushwork offers something new to discover each time we look: the outlines of the lanterns with their blueish-gray shadows and the orange light reflected on the delicate fingers and faces.

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Detail. Muddy Colors.

This is one of the few compositions Sargent painted en plein air in the Impressionist manner. In fact, Sargent’s Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose is likely the one painting that allowed Impressionism to travel to England. It denounces narrative in favor of a more aesthetic experience—a leading trait of Aestheticism, which removed literariness from art and promoted art for art’s sake. It is also deemed the painting that helped revive Sargent’s career after being forced to leave Paris.

What thrilled us all then was the fact that this picture was the first feeble echo which came across the channel of what Manet and his friends had been doing with a far different intensity for ten years or more.

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Detail. Muddy Colors.

Sargent’s correspondence with his family and friends reveals the artist’s struggle to realize Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose. Capturing just the right light at the moment of nightfall proved a great challenge as he only had a few minutes to work each evening—a practice he had learned back in Paris from his friend, Claude Monet.

Time was of the essence. To facilitate the process, Sargent secured a place for his easel and had everything ready before starting to paint. When the flowers died, he replaced them with artificial ones. At the end of each session, Sargent scraped off most of the paints only to begin again the next morning.

I wish I could do it! With the right lighting and the right season it is a most extraordinary sight and makes one rave with pleasure.

Sarah Burns, Under the Skin: Reconsidering Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Detail. Muddy Colors.

Sargent’s poet friend, Edmund Gosse, described how each night, their game of tennis would be interrupted by the artist’s dedication to the canvas: “But at the exact moment, which of course came a minute or two earlier each evening, the game was stopped, and the painter was accompanied to the scene of his labors. Instantly, he took up his place at a distance from the canvas, and at a certain notation of the light ran forward over the lawn with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time, rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only, with equal suddenness, to repeat the wag-tail action. All this occupied by two or three minutes, the light rapidly declining, and then…Sargent would join us again…in a last turn at lawn tennis.”1

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Detail. Muddy Colors.

Housed in London’s Tate Britain, this life-size painting measures 5’9” x 5’1”. Originally a rectangle, Sargent cut 2 ft from the left to centralize the composition, resulting in its square shape. The unusual angle from which the scene is captured — from above and positioned at a slight angle — is reminiscent of Japanese prints, which were in vogue at the time, especially among the Impressionists. The crisp white flowers and lanterns set against the vibrant green foliage offer a striking contrast. Counterintuitively, the flowers become larger as our eye moves upward, contributing to the work’s flatness, another hallmark of Japonisme.

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Museum’s website.

Sargent spent his English summers in an artists’ colony in Broadway, Worcestershire, where he could be found singing around a piano with his close circle of friends. The title of this work comes from the refrain of a popular 18th-century song, The Wreath, by composer Joseph Mazzinghi. The repetition in the work’s title is reenacted visually by the repetition of the painted flowers. Indeed, much like the notes of a musical score, Sargent’s blossoms are scattered across the canvas.

John Singer Sargent, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, 1885-6, Tate Britain, London. Detail. Steven Zucker.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was first exhibited in 1887 at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition, where it received mixed critiques. According to one review of the exhibition in The Art Journal, “Mr. Sargent is certainly the most discussed artist of the year…as artists almost always come to blows over this picture.”2

For Sargent, what saved him from his scandalous portrait proved to be an equally fruitful period of artistic creation. By combining a fresh subject with a new technique, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose was a sensation in its own right. It both redeemed and revitalized Sargent, who would go on to captivate the public with his images for decades to come.

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose is also the front cover of our 2024 monthly calendar—get yourself a copy here!

Sarah Burns, Under the Skin: Reconsidering Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent, p. 332-333.

Sarah Burns, Under the Skin: Reconsidering Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 124, No. 3, Cecilia Beaux: Phildelphia Artist (Jul., 2000), University of Pennsylvania Press.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!