Motherhood, Divorce, Art, and Activism

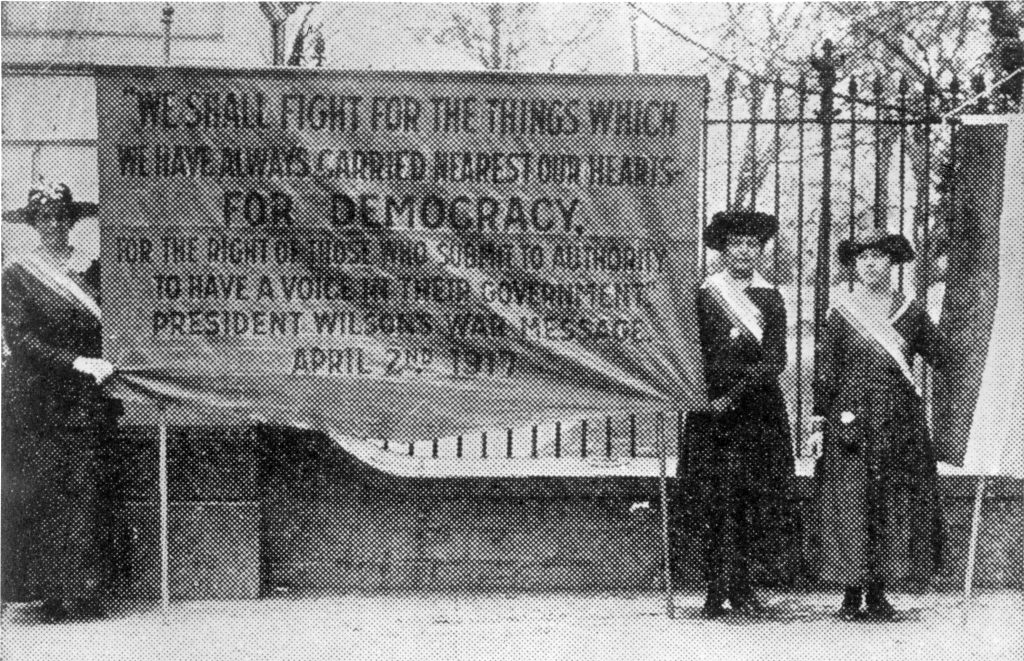

In 1918, Reyneau gave birth to her daughter, Ann, but to the disappointment of her husband, motherhood did not slow her activism or her pursuit of art. This caused friction in her marriage, and the two divorced in 1921.

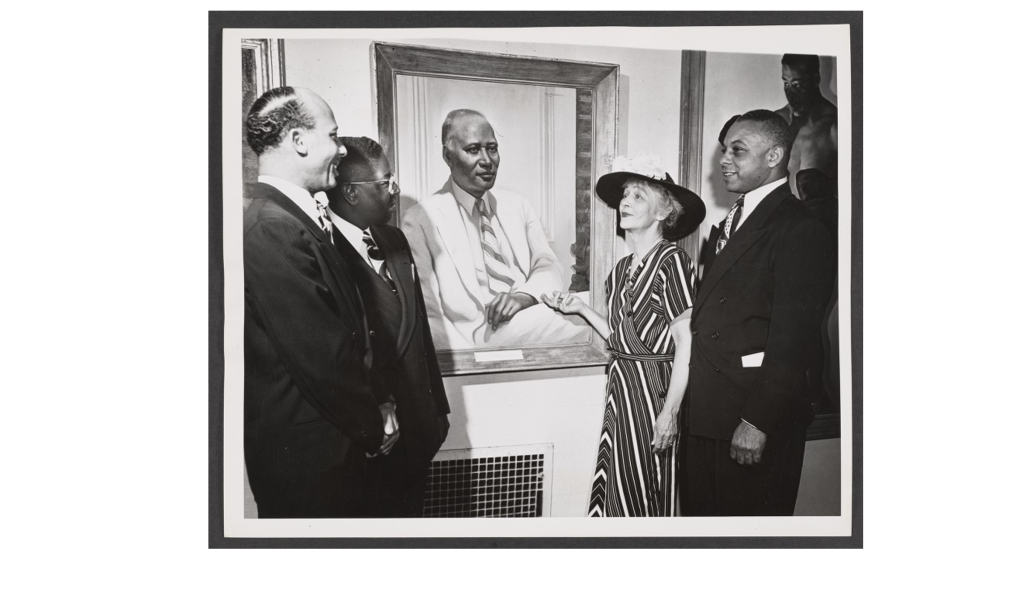

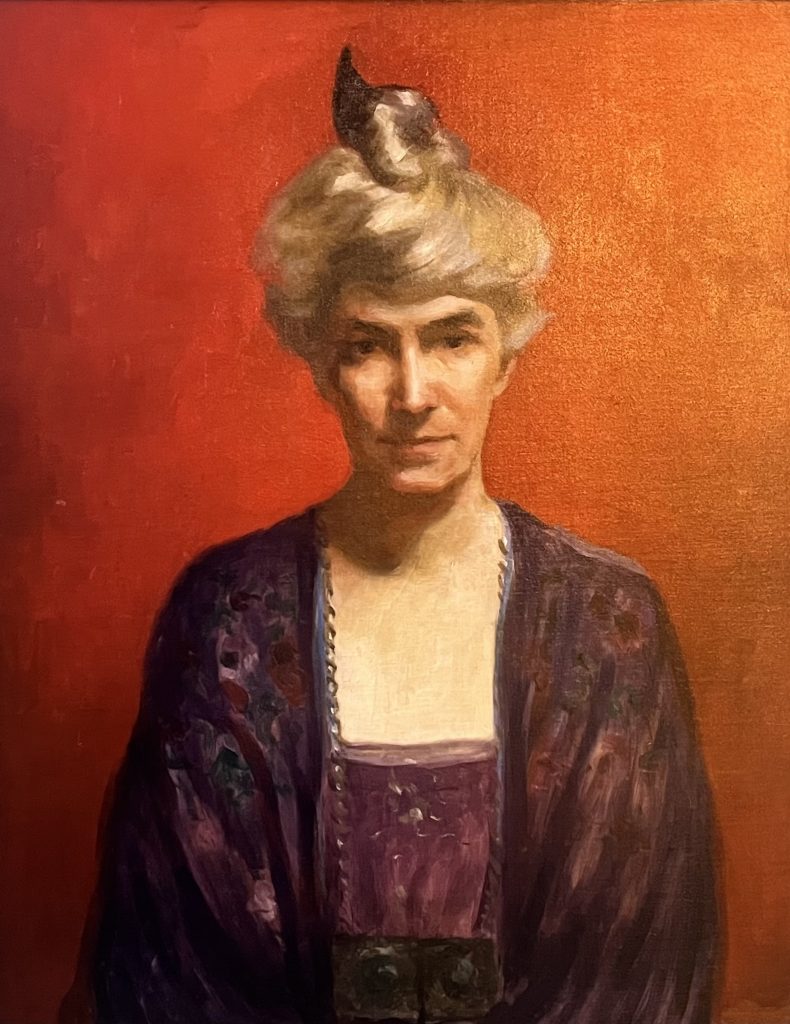

That same year, unbeknownst to Reyneau’s father, the Calhoun County Bar Association hired Reyneau to paint a portrait of her deceased grandfather, Benjamin Graves, to be hung in a circuit courtroom. The portrait was unveiled in a public ceremony, and it was on that day that Reyneau’s father, a scheduled speaker for the event, learned for the first time that his daughter had painted the portrait.

Reyneau continued her activism, and police arrested her again in 1930 on “Red Thursday,” an international day of mass protests on behalf of the unemployed. During the protest, William Smith, a Black cook and butcher walking by the protest, was singled out by police and beaten. Reyneau ran to his aid and was promptly arrested. Later, Reyneau testified in court in Smith’s defense, and he was found not guilty.

For much of the 30s, Reyneau lived in Paris and London, where she continued to grow as an artist. She created art for The Bookman, often contributing portraits of well-known writers. When the Nazi regime rose to power, Reyneau opened her home to Jewish refugees looking for a safe stop en route to America. However, with the threat of a Nazi attack looming, Reyneau returned to the United States in 1939, before the onset of the Blitz.

Return to the United States

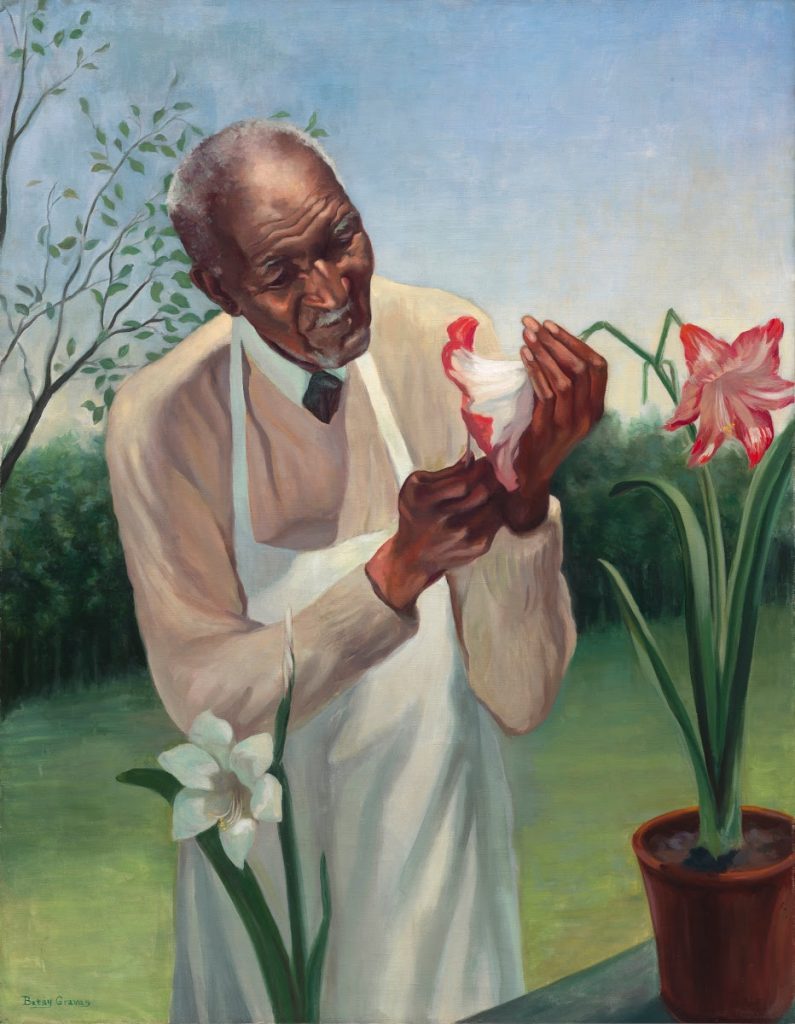

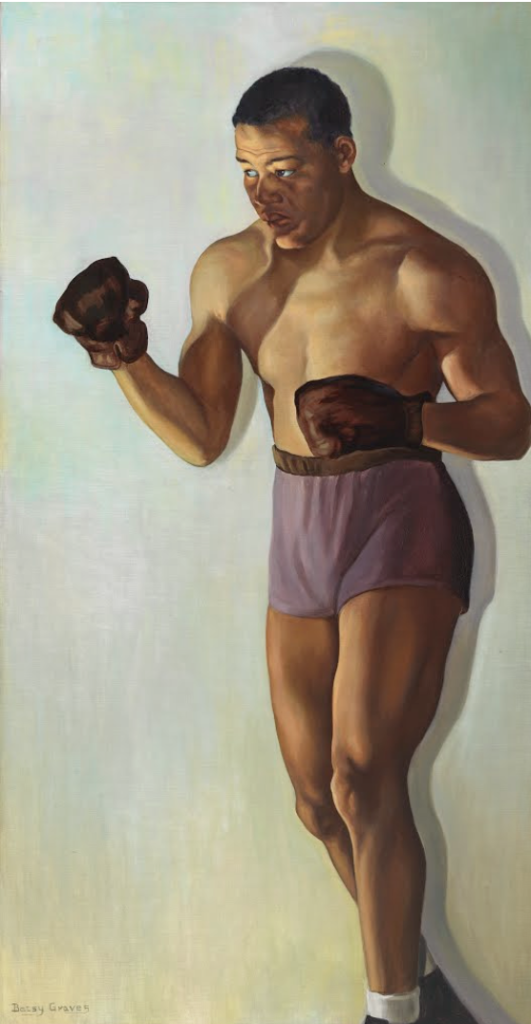

Upon returning to the United States, more than ever, Reyneau saw the hypocrisy of the racial policies in the United States and the similarities between the persecution of Black Americans and those oppressed by fascist European governments. She painted a local Black laborer, Edward Lee, and it was this painting that convinced George Washington Carver, a reluctant subject, to let her paint him as well. The portrait of Carver became the first painting of a Black subject to hang at the Smithsonian, according to the Hartford Courant.