Nakedness or Nudity? To Be a Woman Is to Perform

Throughout the centuries, women’s bodies have consistently been staged for display rather than simply allowed to exist. John Berger’s...

Guest Author 12 March 2026

In the vast panorama of 19th-century Mexican art, few figures shine as brightly as José María Velasco. Born in 1840 in Temascalcingo, State of Mexico, he became the painter who captured the soul of an emerging nation through its landscapes. While others devoted their brushes to mythological or religious scenes, Velasco turned his gaze toward the valleys, volcanoes, and skies of Mexico. His work is a symbol of identity and belonging. Behind this vision awakened his scientific eye for nature.

José María Velasco’s artistic journey began at the Real Academy of San Carlos in 1855. At the time, academic art focused mainly on the human figure. Defying this convention, Velasco turned to landscape painting, then seen as a minor genre, marking the first act of his artistic independence.

His teacher, the Italian painter Eugenio Landesio, played a decisive role in this choice. Landesio taught Velasco not only technique but also a structured way of seeing nature. Through his treatise, The Foundations of the Artist, Draftsman, and Painter (1866), he emphasized perspective, composition, and the poetic harmony of space. Guided by Landesio, Velasco learned to transform the Mexican landscape into more than just a view—into a symbol of identity and beauty, setting the foundation for his later masterpieces.

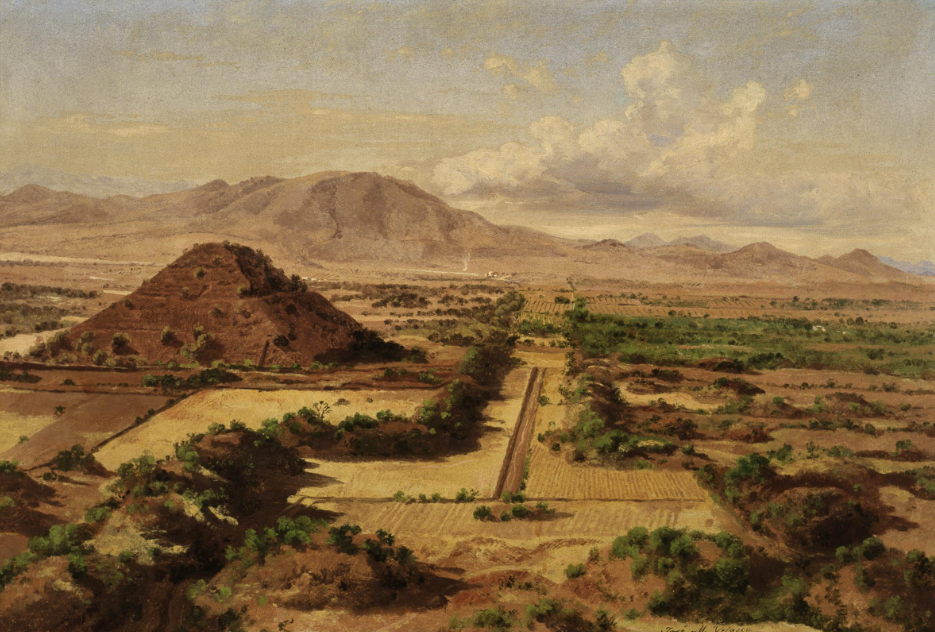

José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico from the Santa Isabel Mountain Range, 1875, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico. Photograph by Steven Zucker via SmartHistory (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Velasco’s transition toward his own style is clear in several key works. We see it in paintings like La Alameda de México (1866) and Cumbres de Maltrata (1875). Admittedly, these paintings still followed academic rules. However, they reveal his growing sensitivity to a unique light and atmosphere, which began to capture the essence of the Mexican high plateau. During this period, his color palette started to shift. He moved away from the earthy, reddish tones of his master, which felt more European, and began to embrace the clear blues and crystalline light of the Valley of Mexico.

José María Velasco, The Goatherd of San Ángel, 1863, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico. National Gallery.

Velasco started to apply Landesio’s complex theories about light. For instance, he explored the effect of a “projected light blaze” in relation to moonlight, as seen in The Great Comet of 1882. Crucially, through his own empirical observation he filtered these lessons. This was no longer a matter of simply reproducing a formula. Rather, he used it to interpret a specific reality at a particular moment. Thus, his training was far from a simple adoption of academicism. It was, in fact, a critical and creative dialogue with his teacher, which laid a firm foundation for his later creative breakthroughs.

José María Velasco, The Great Comet of 1882, 1910, Museo de Arte del Estado de Veracruz, Orizaba, México. Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

During the period from the mid-1870s to the end of the 19th century, José María Velasco established himself as the undisputed master of Mexican landscape painting. This was a period of artistic maturity, marked by growing international recognition. His paintings reached a new level of refinement while reflecting broader ideas shaping Mexican society at the time. They aligned with the Mexican liberal movement influenced by positivist thought, expressing faith in science, progress, and the harmony between nature and nation.

Detail showing Basilica of Guadalupe (bottom left), edge of Lake Texcoco (in the foreground), and Mexico City (in the background) from José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico from the Santa Isabel Mountain Range, 1875, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico. Photograph by Steven Zucker via SmartHistory (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Velasco’s most significant work from this period is The Valley of Mexico (1877). This painting is not only his best-known piece but also a pivotal moment in 19th-century Mexican art. To create it, Velasco climbed the Sierra de Guadalupe in search of the perfect vantage point, carefully observing how light and distance shaped the vast landscape before him.

Technically, the painting is an absolute feat. In it, Velasco displays a masterful use of atmospheric perspective. This technique creates an illusion of depth and distance by adjusting the color and clarity of objects as they recede. As a result, the viewer gets a sensation of almost infinite vastness. For example, your gaze travels from the detailed foreground vegetation all the way to the distant Mexico City skyline, where the volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl appear on the horizon.

José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico, 1877, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico. National Gallery.

The artist captures the light of the valley with remarkable precision, conveying both clarity and stillness. This approach marks changes in his formalism influenced by Landesio. In contrast, his teacher’s landscapes often favored warmer, more conventional tones rooted in European tradition. Velasco, however, applied a rich and realistic color palette, carefully capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the moment.

This painting is also a scientific document and shows Velasco’s extraordinary attention to detail. The artist depicts the mountains with geological precision. The botanical accuracy of the foreground flora and fauna is equally remarkable. We can clearly see the eagle, cacti, magueys, and xerophytic shrubs, all based on his careful studies. As such, the painting functions as an ecological record, capturing a valley before 20th-century urbanization transformed it forever. Consequently, it has become an invaluable source for today’s environmental historians.

José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico, 1877, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico. Photograph by Steven Zucker via SmartHistory (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

With the success of The Valley of Mexico, Velasco undertook an almost cartographic project to capture the diversity and grandeur of the entire national territory. The major works from this period prove his incredible versatility.

This canvas is an example of Velasco’s ability to combine monumental cathedral architecture with the surrounding landscape through precise perspective and careful observation. His attention to the Baroque façade reveals a deep interest in how light and texture work together within the emerging urban scene.

Velasco didn’t simply depict a building. By including nearby mountains, vegetation, and traces of everyday life, he linked the cathedral to Mexico’s broader identity. This approach was unusual in Mexican art at the time, when buildings were often portrayed as isolated monuments rather than as parts of a living environment.

José María Velasco, Cathedral of Oaxaca, 1887, National Museum of Art, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico.

This is considered the first painting in Mexico to depict a locomotive, reflecting the Porfirian ideal of progress at the dawn of the 20th century. However, Velasco’s decision to include a steam train carries additional meaning. Rather than simply celebrating industrial modernity, he integrates the train into the landscape as part of a larger harmony between nature and human invention. His approach contrasts with European artists like Turner or the Impressionists, who often depicted locomotives as symbols of speed and disruption. For Velasco, the train becomes a quiet presence—evidence of change, yet still rooted in the calm order of the Mexican valley.

The Metlac Ravine also creates a harmonious dialogue between human engineering and natural grandeur. The painting serves as a visual manifesto about Mexico’s changing landscape, showing how the expansion of railroads and industrial progress began to shape and connect distant regions of the country. Velasco captured a moment when technology was not only transforming the terrain but also redefining the concept of a unified national space.

José María Velasco, The Metlac Ravine, 1897, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico.

After achieving international success, Velasco’s landscapes were chosen to represent Mexico at major exhibitions abroad. These included the World’s Fairs in Philadelphia (1876) and Paris (1889). There, they earned medals and critical acclaim.

His paintings became Mexico’s visual ambassadors to the world, showing the nation’s growing cultural and artistic sophistication. They reflected progress in science, industry, and technology, while also celebrating the country’s vast and monumental natural beauty. Velasco’s work reminded viewers that modernity and nature could coexist in the same image.

José María Velasco, Pirámide del Sol en Teotihuacán, 1878, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico.

The final stage of José María Velasco’s life reveals a quiet but profound transformation in his art. This decade, which art historian Fausto Ramírez Rojas described as his “years of retreat” and “fruitful dusk,” was not a decline but a period of deep introspection. Velasco began to move away from the grandeur of his earlier nationalist landscapes, replacing it with a more personal and meditative vision. The landscape, once a stage for the nation’s identity, now became a mirror reflecting his own mortality and the fragile rhythms of nature.

José María Velasco, Lumen in coelo, 1892, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico.

Heart problems forced Velasco to resign from his position as professor at the Academy of San Carlos in 1902. Soon after, he withdrew to his home in Villa de Guadalupe Hidalgo, where he continued painting until his death in 1912.

This last period of physical isolation reshaped his art. His palette became softer and more subdued, favoring grays, ochres, and pale blues that suggested melancholy. His brushwork also became looser, focusing less on sweeping panoramas and more on the intimate details of the landscape—skies, solitary trees, and distant light. In these late works, Velasco turned inward, painting not the Mexico of progress, but the Mexico of his memory.

José María Velasco, Árbol de la Noche Triste, 1910, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, Mexico.

Dr. Emmanuel Ortega on José María Velasco and Landscape Painting. Smarthistory YouTube channel, Apr 21, 2021. Accessed: Nov. 25, 2025.

Introduction to José María Velasco, National Gallery. Accessed: Nov. 25, 2025.

Nicholas Wroe, “Borderline Genius: How José María Velasco’s Landscapes Redefined Perceptions of Mexico,” The Guardian, Mar 17, 2025. Accessed: Nov. 25, 2025.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!