Given that March is the Women’s History Month you may find this a bit subversive, but in the interest of equality we visited Barbican’s exhibition Masculinities: Liberation through Photography. In Barbican’s own words ‘through the medium of film and photography, this major exhibition considers how masculinity has been coded, performed, and socially constructed from the 1960s to the present day.’

The Setting

As is typical for Barbican, the exhibition utilizes the entire two-level space. So make sure you come prepared to spend well more than an hour here. No snacking! Another aspect typical of Barbican is that the exhibition is dead serious and very intellectual. It’s not meant to be a feast for the senses but a challenge for the mind. Once you get into that head-space, or if you come prepared it’ll be fine.

The exhibition deals with the ways masculinity has been constructed and presented in our culture. The starting point is the Simone de Beauvoir quote: ‘one is not born a woman, but rather becomes one’. In the same way, here masculinity is treated as an artificial, cultural construct. To put it simply, it is a box or a series of boxes into which men are shoved. Thus, in order to fit in one must comply, and at some point it becomes almost natural. The show walks us through a series of such boxes as well as attempts to break free from them or to subvert them.

The Journey Through the Boxes

The exhibition space is cleverly arranged so that each room indeed brings to mind a box. However they are interconnected in surprising ways. They give us a glimpse not only of the art pieces in the other rooms, but more importantly of the other viewers and their reactions. This keeps us on our toes, it makes us aware that as we watch we are also being watched. This is exactly the point of abiding a socially constructed identity; the ever-present observation and judgment, the effort to fit in and meet the expectations. It drives its point home through the works presented but also on a meta-level.

Archetypes

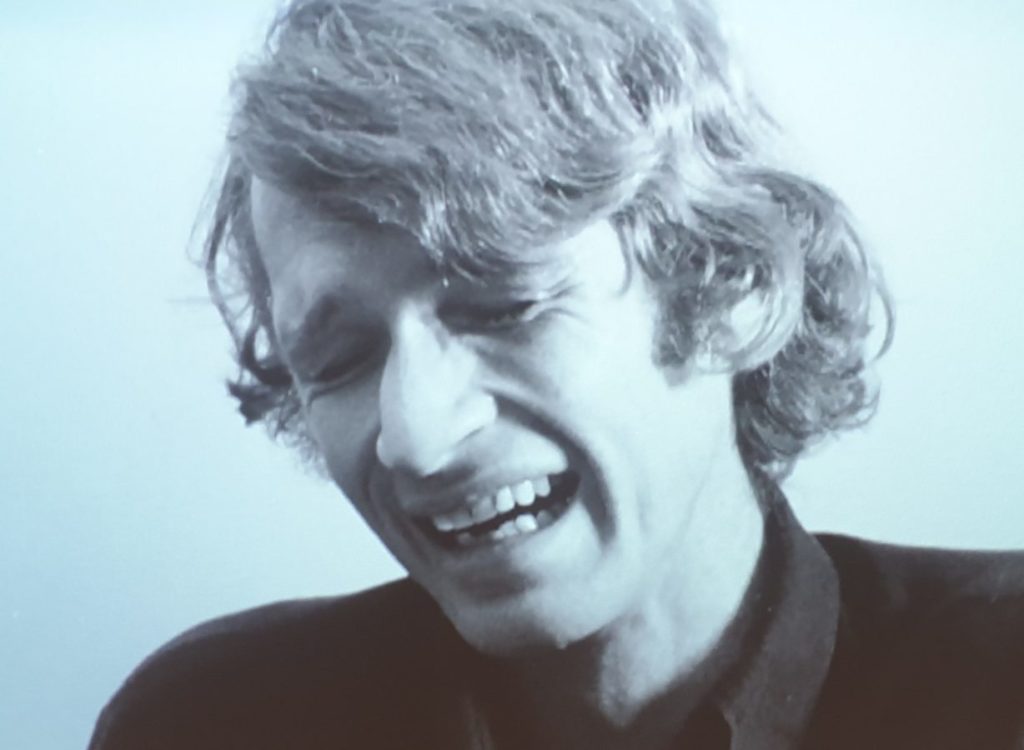

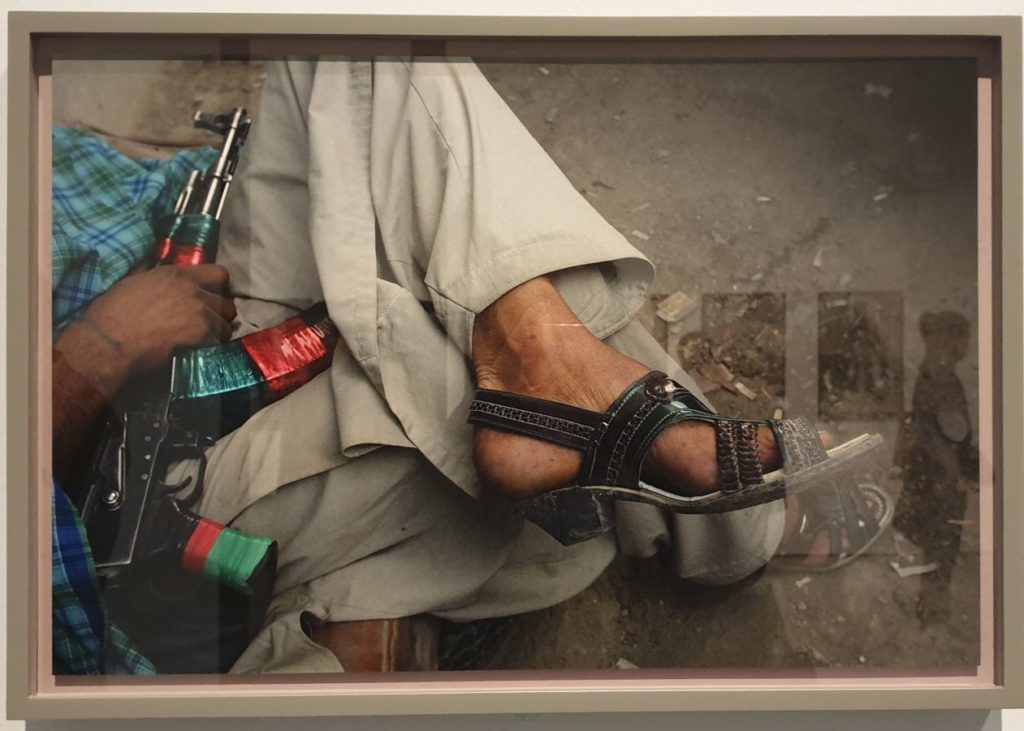

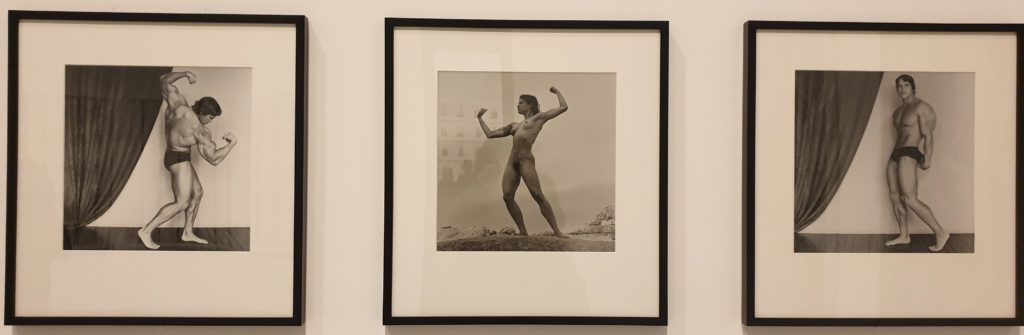

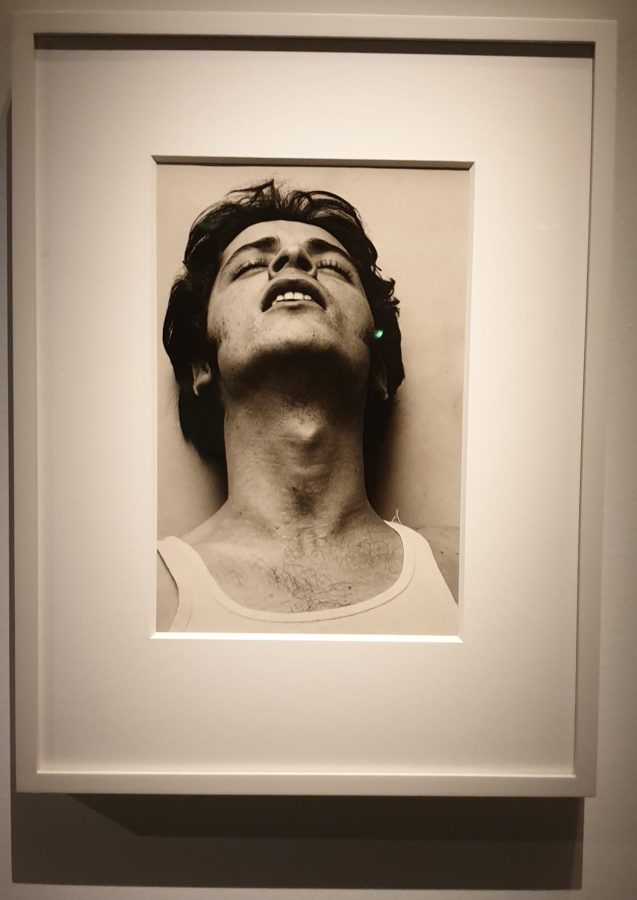

The first box we visit is the most literal one – archetypes. First and foremost: man as a soldier, the defender, the fighter, the warrant of safety always on the right side, always strong. Then we move on to others: bullfighters, cowboys, athletes, etc. All the manly men are represented but each artist disrupts those archetypes in their work. Whether it’s defenseless sleeping soldiers, decorated Kalashnikov with a foot in high heel shoe, a homoerotic image of a cowboy, the bullfighters slightly worse for wear after the show, a crying man (gasp!). All the way to the body of Arnold Schwarzenegger compared to Lisa Lyon’s by Robert Mapplethorpe.

In fact the archetype of the manly man (however we dress it) is unsustainable, unachievable and a fake. Manly men are not real people, they do not exist, yet men are made to strive to become one. In the same sense women are meant to strive to become a supermodel or any other of the many female archetypes. None of the archetypes hold, yet all of them perpetuate in our society.

Power

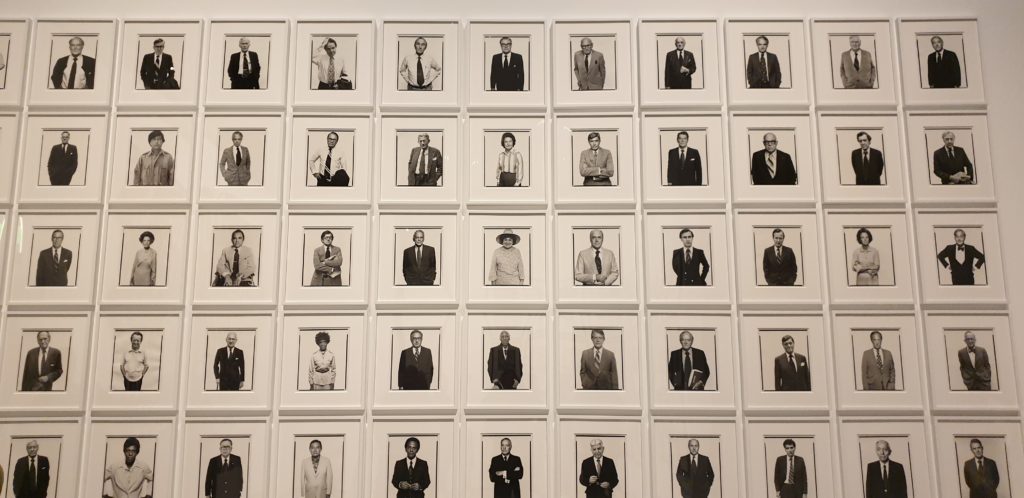

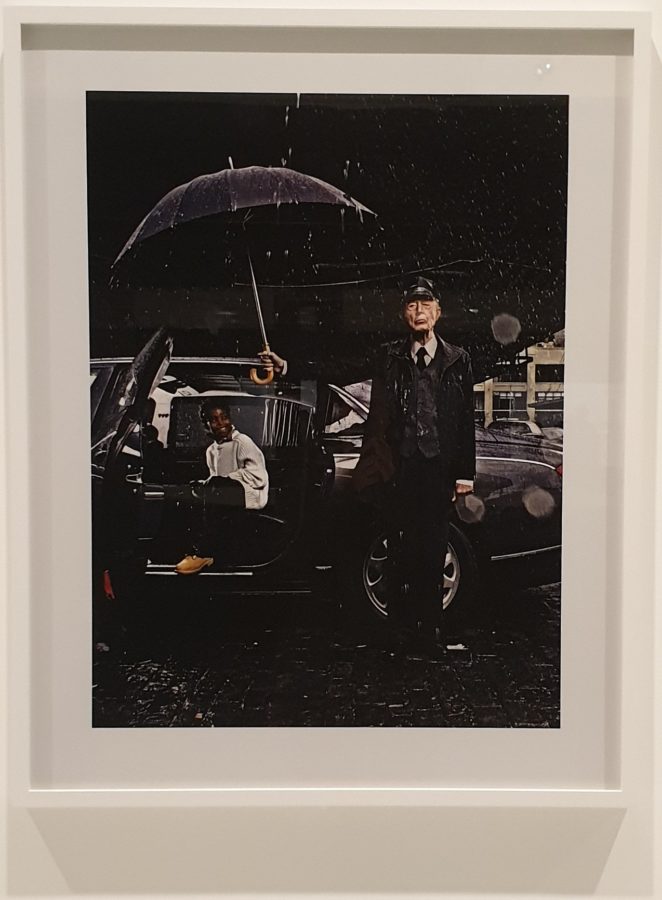

Next we move to the subject of power where cunningly Richard Avedon’s Family is juxtaposed with Piotr Uklański’s The Nazis. This makes us ask ourselves a question about the nature of power and its representation. How power corrupts (forgive me the cliché) and how the elitist environments such as gentlemen’s clubs and fraternities enable ‘toxic’ masculinity. This breeds arrogance, an extreme sense of privilege and a dissociation from the needs of anyone from the outside, and even contempt for them.

Family

Next things become a little bit gentler as we dive into the family space. The works become a lot more personal and less about the public presentation. Artists take from their personal experiences and expose their inner thoughts on the meaning of being a father, and on the impacts of good and bad fatherhood on a family. Here we get everything from a gentle look at an aging father, to an alcoholic, and all the way to a violent abuser.

This is also one of the few places in this exhibition where you can find playful work. For example, Hans Eijkelboom happily assumes the role of the father figure in other people’s families. On random afternoons he’d knock on strangers’ doors (assuming that’s when the fathers/breadwinners would be at work). He then would persuade the home-bound women to take family photos with him standing in for the absent father. Thus he challenges existing gender roles.

Queer

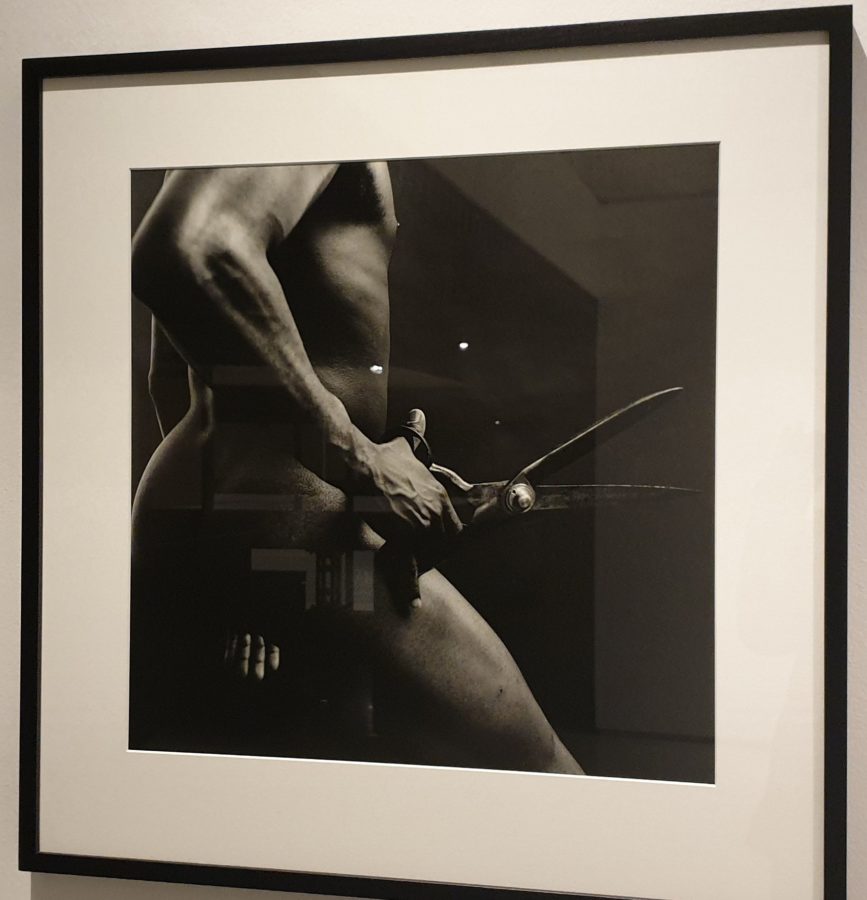

As we move upstairs, the first space we enter is queer. It subverts all the roles we’ve just seen. Breaking free from all the boxes, fighting for new freedom. Yet, to me, it felt like just another box. Yes, an important one considering the fight for gay rights, but a box nonetheless. A box constructed in opposition to, or as a negative of the previous ones. The works challenge the status quo, but with time also shoehorned masculinity into another corner.

Black Bodies

Here we consider the male experience and masculinity through the lens of race. It becomes all the more complex because of it. Now it’s not only about the gender, but also race. There is an intrinsic connection between the two but it also forges a whole new host of archetypes. Archetypes that need to be broken down and understood to be dismantled. To allow men to defend themselves from them.

On one hand we have the body itself, the perception of black bodies formed by a violent history of slavery and prejudice. On the other hand we have the class and privilege, forged by corporate America, perpetuating and reinforcing stereotypes. The fight for a distinct identity is far from over in this space.

Women on Men

The last space reverses the point of view. It is no longer men representing men, but women sharing their view. We begin with deeply feminist works of the 1960’s and 1970’s objectifying the male body to show how oppressive the male gaze is, through its reversal. Later we see attempts at crossing the line and getting the first hand experience (or as close as possible experience) of the other gender.

In Conclusion

Does the exhibition meet its set objective? Absolutely. We get an honest analysis of how masculinity has been constructed in culture (mind you, it is still a very western view). It shows a catalog of possible masculinities from which men can pick and choose. We see them in box after box. It also shows attempts at breaking down those boxes. Sometimes they are successful, but more often ending in yet another, unexpected box. A bit like in Cube.

This is where the only weakness of this exhibition lay for me. It is all about representations, all about perceptions, about forms, about types. There is hardly anything about Humans. What is the point of breaking the box apart, overcoming the stereotype, when we instantly shove ourselves into another one? This suppresses our individual experience, we yearn to be part of a group, to be accepted. Even if it comes at the cost of our individual expression and freedom.

It is an excellent exhibition about the types of masculine constructs in our culture. It is though, a horrible exhibition about men. We are warned about this form the beginning. It s food for thought, but not for the emotions. The show challenges and makes you think, but at the same time is difficult to connect with on an emotional level.

Masculinities. Liberation through Photography

Barbican, Art Gallery

20 Feb – 17 May 2020

Standard ticket £15-17

The exhibition is on our 15 must-see art exhibitions list for 2020.