Joséphine de Beauharnais: Patron of the Arts

Joséphine de Beauharnais was born in Martinique as Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie. She evolved into the sophisticated and cultured...

Maya M. Tola 20 May 2024

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz was a 17th-century nun and the first published feminist poet of the New World. Her written works display her sense of wit and inventiveness, as well as her wide range of knowledge. A self-taught scholar in Mexico’s colonial period, she is considered one of the most important Hispanic literary figures whose radical feminist views revolutionized not only Mexico but the Americas at large.

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana (1648-1695), also known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, was born in San Miguel Nepantla, a small village in Mexico. As a child, Juana was precocious and exhibited a strong desire to learn. She devoured her grandfather’s books and learned Latin by the age of four. Living at a time when women had little access to education, Sor Juana was almost entirely self-taught and wrote her first poem at the age of eight. As a young woman, rather than marry, she decided to take her vows and join the Catholic Convent of San Jerónimo where she would remain for the rest of her life to pursue her love of learning.

Life in the convent was not dull and uneventful—on the contrary, it afforded Sor Juana the opportunity to study, write poetry and plays, and even teach music and drama. She worked as the convent’s archivist and accountant, and even became the unofficial court poet despite being cloistered. Sor Juana was interested in rhetoric, mathematics, natural sciences and the visual arts. She regularly corresponded with other intellectuals and even amassed one of the New World’s largest private libraries in her living quarters.

Miguel Cabrera, Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, 1750, Mexico City, Museo de Historia, Smart History.

In this posthumous portrait by Mexican artist Miguel Mateo Maldonado y Cabrera (1695-1768), Sor Juana is assertive and stoic as she directs her gaze toward us. By depicting her seated in her library, surrounded by books and other instruments of learning, Miguel Cabrera elevates Sor Juana’s status as an intellectual. Similarities can be drawn between this portrait and the many depictions of St. Jerome in his study, which showcase the Christian priest’s erudition.

Sor Juana sports the habit of her religious order, the Jeronymites, and wears a typical escudo de monja (“nun’s badge”), which features the Virgin Mary. She clutches a rosary with her left hand, and with her right she turns the page of an open book—a text by St. Jerome. The red curtain, commonly seen in elite portraiture, denotes her high status. The books featured in her library include volumes on philosophy, theology, natural science, history, and mythology.

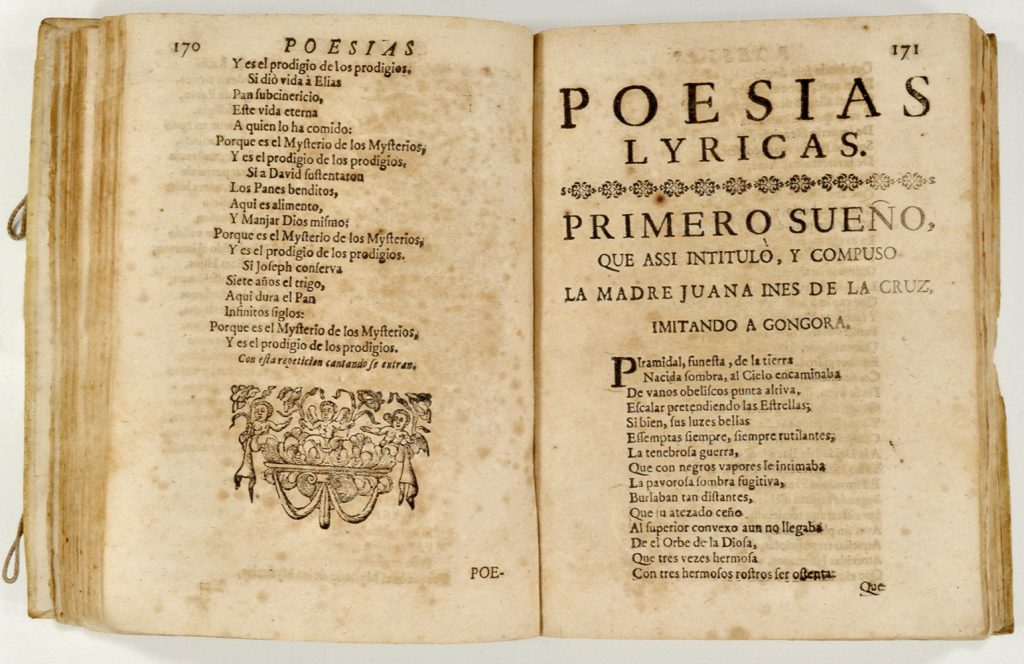

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Primero Sueño. Originally published in 1692. Project Vox.

A prolific writer with radical feminist views in the ultra-Christian New Spain of the 1600s, Sor Juana held a unique position. She is considered the first published feminist of the Americas—a collection of her poetry was first released in 1689. A fierce advocate for women’s right to education, she revolutionized not only Mexico but the New World at large.

In her longest poem, an epistemological meditation entitled First Dream, Sor Juana expressed her desire to understand the order of the universe and her place within it. She used the convoluted poetic devices of the Baroque to describe the soul’s quest to gain total knowledge.

In 1691, she steadfastly defended her right as a woman to pursue scholarly endeavors. Her famous response to the Bishop of Puebla, Reply to Sor Philotea, is credited as the first feminist manifesto:

One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper.

Sor Juana criticized the double standards and injustices of her day. In her strikingly modern poem, Foolish Men, she uses antithesis to highlight the hypocrisy of men who blame women for the very flaws their male-dominated society has produced:

You foolish men who lay

the guilt on women,

not seeing you’re the cause

of the very thing you blame;

if you invite their disdain

with measureless desire

why wish they well behave

if you incite to ill.

You fight their stubbornness,

then, weightily,

you say it was their lightness

when it was your guile.

Sor Juana not only held a progressive worldview, she raised controversial questions in a highly oppressive society. After years of boldly standing up to those who wished to silence her, Sor Juana was forced to sell her library for alms, and ultimately gave up writing. She subsequently dedicated herself to service and died in 1695 while tending to her sister nuns during the plague in Mexico City. For centuries, Sor Juana remained largely undiscovered until 1900, when many of her works were published. Her creative genius and lifelong pursuit of learning have made Sor Juana a national icon of Mexico, and one of history’s most influential female figures. In the words of esteemed poet Octavio Paz, “It is not enough to say that Sor Juana’s work is a product of history; we must add that history is also a product of her work.”

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!