Indus Valley Civilization: Echoes of a Forgotten Past

Nestled in the plains of present-day Pakistan and northwest India lies one of the world’s most enigmatic ancient societies: the Indus Valley...

Maya M. Tola 28 August 2025

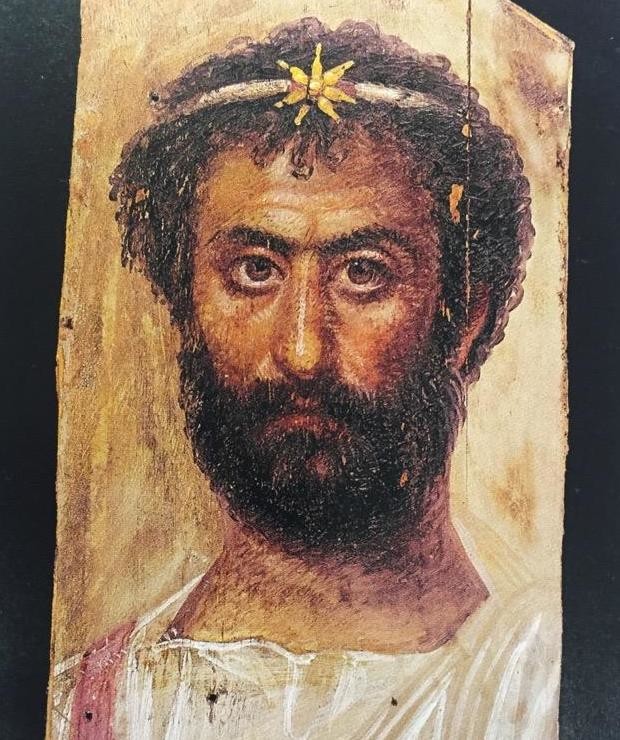

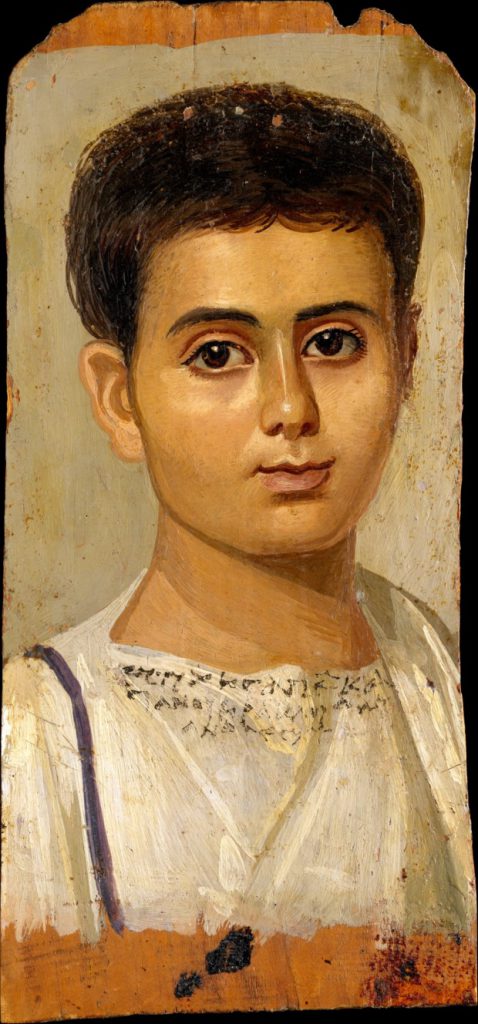

Though they are often referred to as “Fayum portraits”—taking their title from the location of a region in Egypt where Pharaoh Amenemhat III‘s mortuary temple once stood—they came from various places across Egypt. These ancient Egyptian-Roman “death masks” are far more naturalistic than anything seen in the western hemisphere for at least the next 600 years.

After the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra by Octavian in 30 BCE, Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire. Romans trickled into their new African territory and assimilated well within the existing culture. That is to say, they left a mark on the former empire that can still be seen to this day—particularly in the incorporation of Greco-Roman style in Egyptian death rituals.

As many are aware, the Egyptians had an elaborate preoccupation with death and the afterlife that tied closely into their religion, politics, and therefore daily life. The Great Pyramids of Giza, the lot of which are considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, are massive mausoleums erected for several of Egypt’s former pharaohs. Intricate gold masks inlaid with precious stones were placed over the heads of mummies to forever idolize the likenesses of the faces beneath them.

The Romans, too, had their own rituals surrounding burial, though they were not nearly as extravagant – or permanent. After the death of a citizen, a procession was often held in which mimes and dancers performed as one’s ancestors. The body itself was carried through the streets on a platform known as a bier. Afterwards (as was the case for most of Rome’s history) the body was cremated. But around the 2nd century CE—after Rome had conquered Egypt—inhumation became more commonplace.

At this time, delicately crafted portraits of the dead were placed atop their caskets. The practice of burial in a sarcophagus and the creation of a likeness to place over the deceased’s head was taken from Egypt, while ancient painting techniques were drawn from the Romans—who, in turn, had inherited them from the Greeks.

Encaustic is a medium made of pigment, beeswax, and other ingredients such as linseed oil and egg; most of the Egyptian-Roman death masks were produced using such a mixture. The style of painting, in which faces were depicted realistically (if not idealistically), had existed since classical Greece (4th to 5th centuries BCE).

The eyes of the subjects in particular are most unique, with large, round pupils and heavy lids. They shine with a light that is indicative of the life that had left those of the faces beneath them, bringing a somber sobriety to each portrait.

Though they are often referred to as “Fayum portraits”—taking their title from the location of a region in Egypt where Pharaoh Amenemhat III’s mortuary temple once stood—they came from various places across Egypt. There is evidence to suggest that many of the mummies excavated in the area came from all over the state, suggesting that the Romans there had thoroughly embraced the native culture and practices. Fayum was a sacred site; if you had the money and the religious inclination, you were to be buried there.

From this region came the greatest collection of this kind of portraiture. As a result, “Fayum” is now used to describe the style of painting more so than the actual location of the burials.

The Egyptian-Roman “death masks” are far more naturalistic than anything seen in the western hemisphere for at least the next 600 years. As with many of the advances achieved by the Greeks and lost by the Romans, painting of this quality remained lost until the birth of such masters as Rembrandt and Vermeer.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!