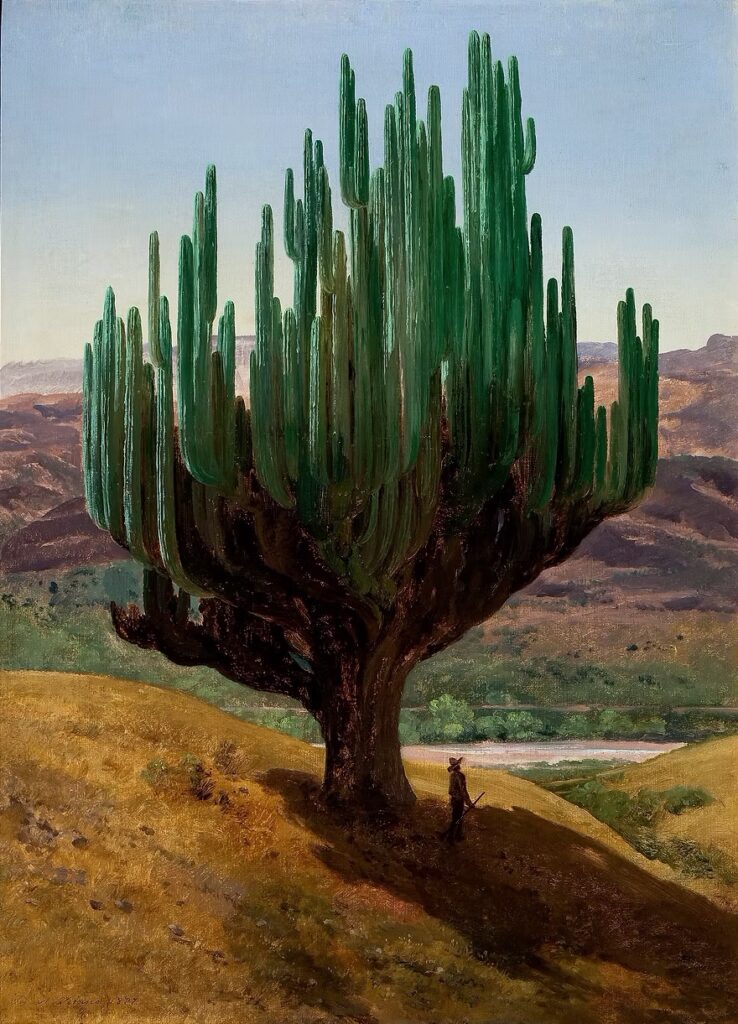

A cardón (Cereus candelabrum, commonly known as candelabra cactus) dominates a canvas measuring 24 in. × 18 in. (61 cm × 46 cm). Resembling an inverted chandelier, this giant cactus stands alone on a hill painted in yellows and brown tones. Below the cactus, a man is taking cover from the scorching sun under its shade. The darkness and the distance blur his features, but the tilt of the hat reveals that he is looking up towards the right. A river or a road surrounded by greenery runs across the background. Further away, the arid hills disappear with the distance. There are no clouds in the sky, and although the sun is not visible on the canvas, the shadow of the cardón suggests the source of light comes from the upper left corner.

José María Velasco

José María Velasco Gómez (1840–1912) was born in the State of Mexico, a neighboring state to Mexico City. He studied painting at the Academy of San Carlos under the instruction of Eugenio Landesio, professor of landscape painting and perspective. His works earned him national and international recognition in exhibitions like the Mexican National Fine Arts Exposition of 1874 and the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. His art helped highlight the landscapes of Mexico and its national identity.

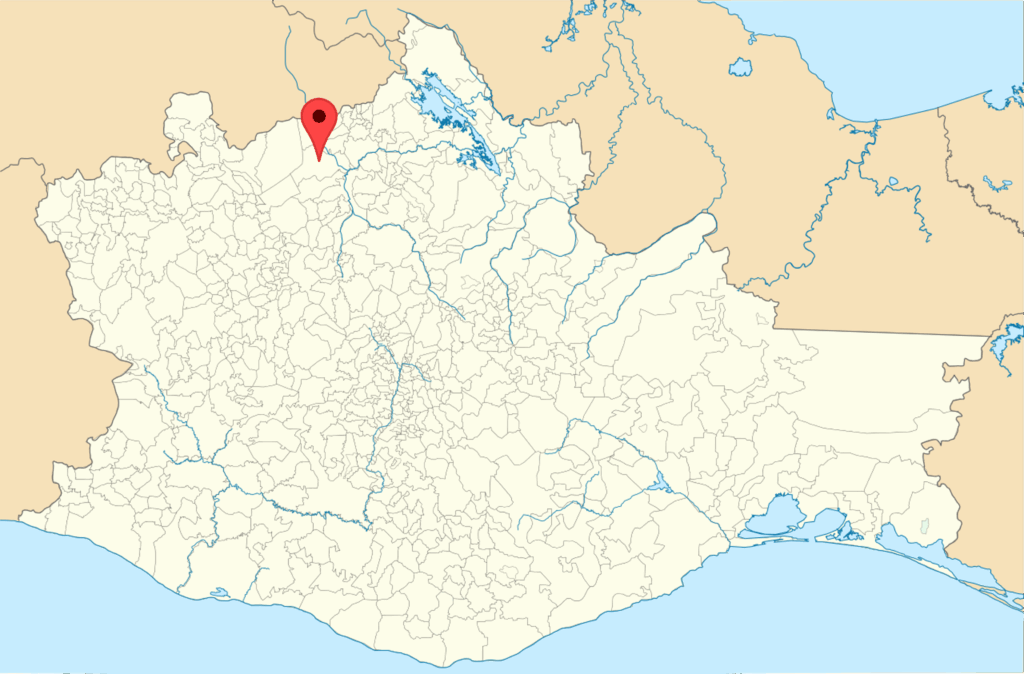

Oaxaca, Mexico

In the early stages of his career, Velasco mostly painted landscapes of the Valley of Mexico. Such a regional focus received criticism from writer Ignacio Altamirano, who believed Velasco’s art stemmed from a centralist perspective. He asserted: Everything Velasco had put out revolved around the capital. For Velasco, it was because traveling was difficult. He had to camp on-site and put together detailed sketches and notes before the actual composition. Luckily, the expansion of the railways in 1873 enabled Velasco to work on subjects further away.

In 1886, Velasco traveled south to paint the Cathedral of Oaxaca as commissioned by the bishop. He took advantage of the trip to visit other parts of the region. He painted Cardón, State of Oaxaca, in the Municipality of Tecomavaca in the northwest of the state.

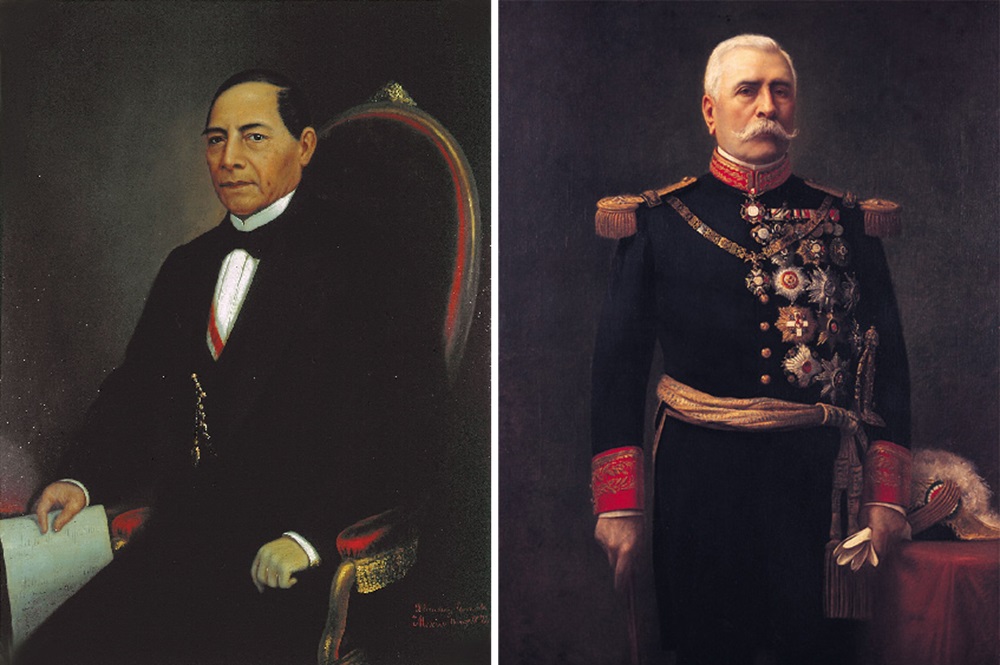

Oaxaca had great political and symbolic importance at the time. It was the home state of two Mexican presidents: Benito Juárez (1806–1872) and Porfirio Díaz (1830–1915). The former governed the country from 1858 to 1872 and fought against the French intervention and the imposed empire of Maximilian of Habsburg. The latter was president in Velasco’s time, who fought another wave of French aggression.

The Mexican Natural World

The Mexican natural world had been the subject of interest and artistic inspiration for decades before Velasco’s time. However, foreigners were dominating the field. Velasco wanted to bring more local representation to the table. As a member of the Mexican Society of Natural History, Velasco made illustrations of flora and fauna from different geological eras. Cardón, State of Oaxaca, could have been another of those hand-drawn images of unique flora found in the country. Yet the candelabra cactus it featured ended up becoming more than just an illustration. It has become a symbol of Mexican identity.

Historian Andrés Reséndiz reminds us that Velasco’s paintings did not replicate the real landscape. As an artist, Velasco also considered the aesthetic and symbolic purposes of his work and made alterations when necessary.

The Rural World

The industrialization of the country in the second half of the 19th century shaped the representation and perception of the rural world in Mexican art. The image of the countryside brought a sense of longing in the urban population. Meanwhile, that same countryside became a symbol of national identity. Those are the driving factors behind the success of paintings like Cardón.

Man vs Nature

Cardón, State of Oaxaca is not like any of Velasco’s famous panoramic depictions of valleys. It rather zoomed in to portray the magnificence of nature with just one element. The man standing next to it not only recalls rural life but also allows the viewer to get a sense of the cardón’s imposing size. Even the trunk of it is more than twice as tall as the man. These cacti can grow up to 60 feet tall. Such a sight evokes awe just as the Romantic landscapes of the 18th and early 19th centuries did, which we now call the sublime.

Cardón, State of Oaxaca belongs to the National Museum of Art’s collection in Mexico City, along with other precious landscapes by Velasco.

Currently, this piece forms part of the exhibition José María Velasco. A View of Mexico in the National Gallery in London, UK (on view until August 17, 2025)..