Diana in Art: Goddess of the Hunt

As the Roman goddess of hunting, the moon, and nature, it is unsurprising that Diana is often depicted among animals and nature in art. Throughout...

Anna Ingram 8 September 2025

Art and tourism have a long and complex relationship. At the peak of the Grand Tour in Rome in the 19th century, countless artists had made a living selling souvenir art to wealthy, Romantic tourists. Salvatore Busuttil, a prolific artist from Malta, was one of them.

Tourism can be a blessing and a curse for host cities. Today, we are witnessing a wave of anti-mass tourism protests across Europe because of the traffic it drove. Tourism in the 19th century, however, brought people and art together.

When we think of souvenirs today we often think of mass-produced objects drenched in kitsch and reproducibility. Here is another perspective on what a souvenir could be.

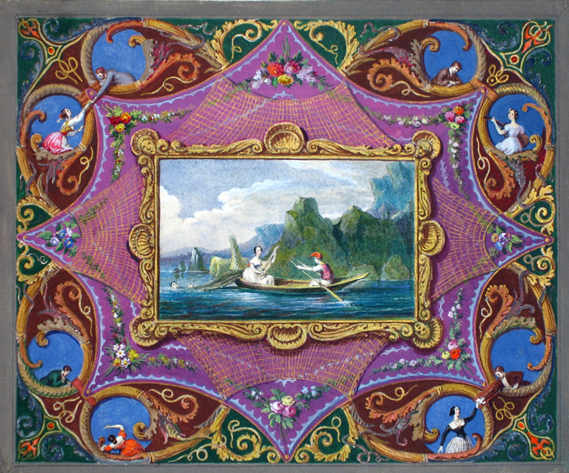

Salvatore Busuttil, Scene with Man Rowing and Woman Playing a Musical Instrument, gouache on paper, MUŻA, Valletta, Malta.

This miniature gouache by Maltese artist Salvatore Busuttil, was created in the mid-19th century for the largely northern European elite tourists traversing the ancient city of Rome on their Grand Tour.

Salvatore Busuttil (1798–1854) was a Maltese artist who spent most of his professional life in Rome. He studied at the prestigious Accademia di San Luca. He was known for his paintings, but his creative output is mostly prints and gouaches. The Academy’s library holds a collection of almost 7,000 artworks by Busuttil.

Salvatore Busuttil, Pantheon, gouache.

Dramatic scenes of Rome’s touristic sites prevail in Busuttil’s works. These were the same places frequented by literary figures like Lord Byron, Goethe, Mark Twain, who experienced the culture first-hand. His approach is reminiscent of Piranesi’s iconic depictions of Rome a lot—grand architecture, teeming life, small figures. All those works have a point of view that caters to his clientele. The latter asked for Romantic visions of Rome’s ruins, and Busuttil delivered. This gouache print depicting the Pantheon, for example, bears a striking resemblance to a 1757 etching of the great master Piranesi.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Teatro di Marcello, etching, 1757, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

Comparing Busuttil’s oeuvre to a master like Piranesi helps clarify the fact that Busuttil—and other vedutisti like him—were not simply commercial artists. The fact that these artworks were created for commercial purposes in no way diminishes their status as serious works of art.

In Rome Busuttil befriended another prolific artist, Bartolomeo Pinelli (1781–1835). Pinelli was a popular illustrator who made his name depicting the customs and traditions of Rome. His energetic draughtsmanship was pseudo-Romantic and his spontaneity was almost modern in its freedom. Pinelli and Busuttil travelled extensively across Lazio and the Campana documenting the customs and costumes of the region, in the hope of preserving them in the face of future Italian unification, as seen in the drawing below.

Bartolomeo Pinelli, Interior of a Roman Inn, watercolour on graphite, 1817, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA.

This brief look into Busuttil’s life in Rome can help lead to a deeper understanding of what is art. At the time, a thriving souvenir market existed long before mass production, catering to prestigious participants of Grand Tours. Viewed in this light, these souvenirs should be appreciated and analyzed as serious works of art. Next time you are in Rome, after buying yourself a Pope bobblehead, find a local artist and buy something from their workshop—you will be part of a long, noble tradition.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!