Summary

Leon Golub was a history painter focused on brutal images of war. Read about his well-known series Gigantomachy, Vietnam, and Interrogation which show the violence of the oppressors and give voice to the suffering.

Western painting through the ages is full of images of flaying, broken bodies, rapes, massacres, murders, and battles, and there is an undeniable haemo scopophiliac tendency that runs through Western visual culture’s reception which Golub’s painting self-consciously explores and enacts. Mimesis and violence are both so fundamental to human beings that one can place them on the level of instinctual, and in Golub’s paintings, they are things of inherency, rather than mere ubiquity. However historically specific a depiction of human brutality may be, it will always have a faint odor of the eternal.

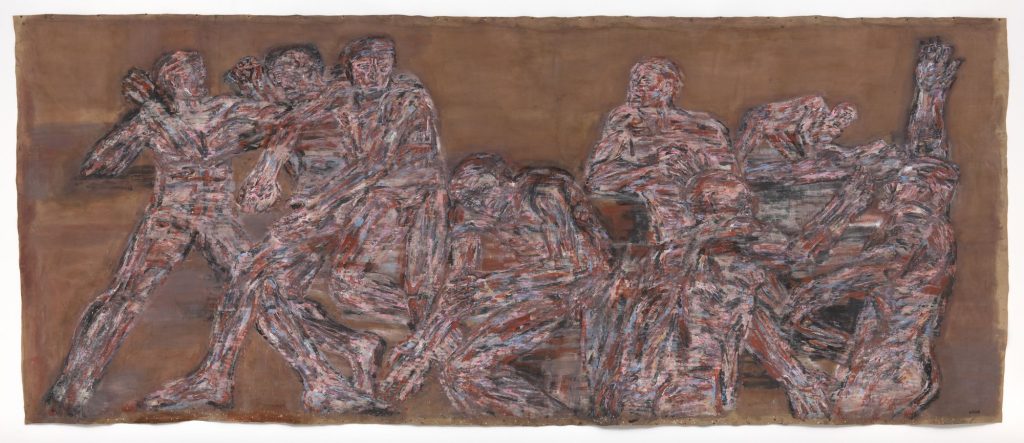

This eternality of brutality is deliberately foregrounded as a subject in Golub’s Gigantomachy and Burnt Man series, but I would argue is equally as present in his Napalm, Vietnam, Interrogation and Mercenaries series. By 1966, with Gigantomachy II, which is a monumental 9 x 24 ft (303.5 x 758.2 cm), Golub was using the scale as a rhetorical mode. The oversized figures on his large canvases tower over and menace us, an effect achieved in part by hanging his unframed, unstretched canvases at floor level. The historical continuity suggested by the painting through its melding of influence from Columbian masks, cave art, and pre-Hellenic sculpture, is not just one of style only, but also the historical continuity of never-ending human barbarity and conflict.

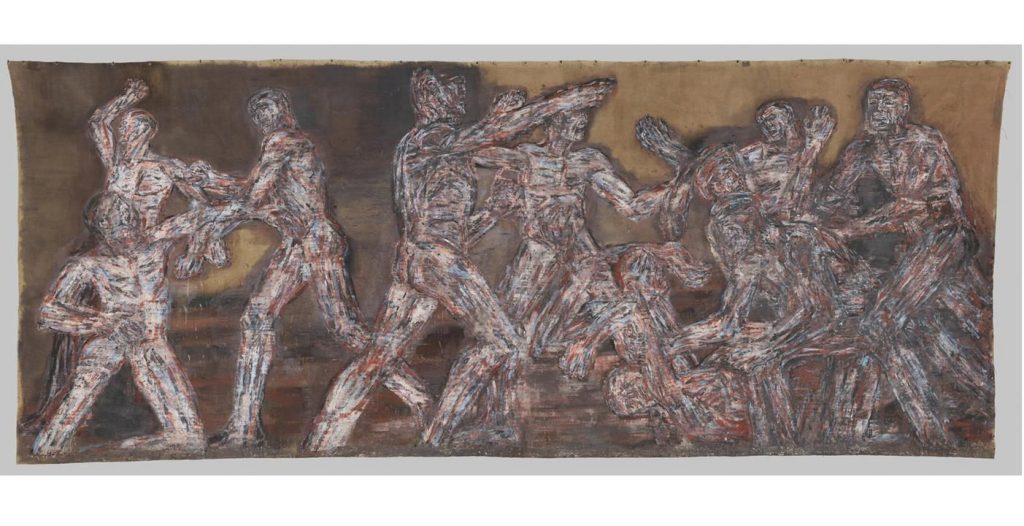

Leon Golub, Gigantomachy II, 1966, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA.

Gigantomachy II depicts a group of naked men engaged in murderous hand-to-hand combat. Its main source was the frieze of the Great Altar of Zeus at Pergamon, c.180-160 BCE, so there is little suggestion of depth, and just enough recession for the figures to fit before and behind each other. Although the title refers to a battle between the Olympian Gods and the race of giants from Greek mythology, there is nothing to differentiate the two warring sides in the painting. The only suggestion that there are different “sides” is given by the ground, which is split almost equally into two with a darker, excremental ground on the left and a lighter brown on the right.

Unlike later paintings, Golub is not depicting the oppression of the weak by the strong but is making a generalized, essential statement about male aggression. Strong vertical and horizontal gouges and thick stripes of paint evoke scar, bruise wounds and blood, dried and fresh, in a violently Expressionistic style he dubbed “barbaric realism”. The faces of some figures in Gigantomachy II are barely discernible, are abbreviated and schematic, and the battling bodies seem like one enormous writhing mass of human flesh at war with itself, forever.

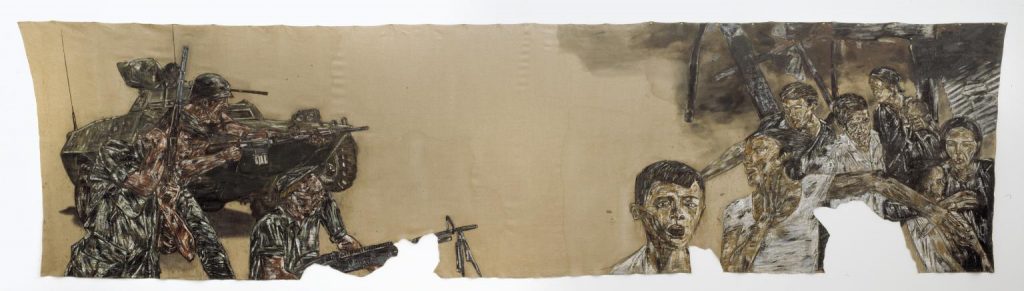

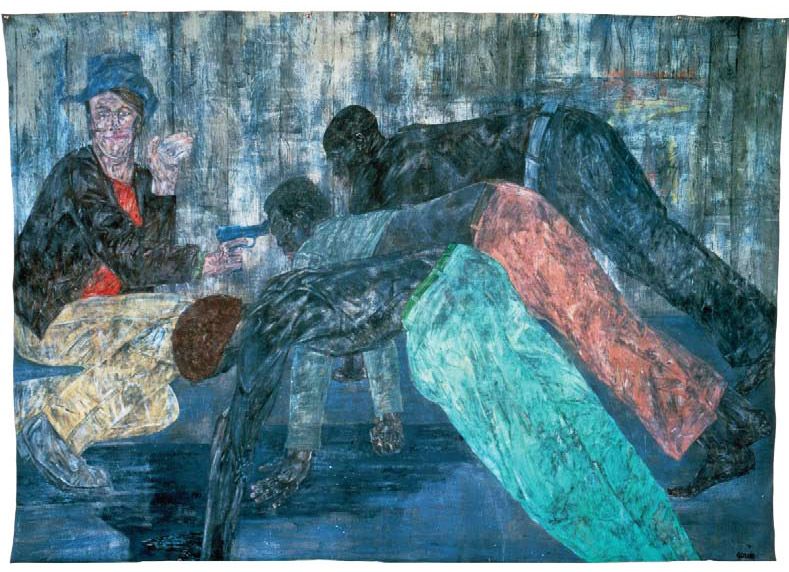

Leon Golub, Vietnam II, 1973, Tate Modern, London, UK.

By the time of Vietnam II, Golub had abandoned these hieratic, classically influenced figures and was using photographic resources almost exclusively, beginning to amass what grew to be a massive archive. Its sources were eclectic, but its subject matter was monotonous: the violence of men.

With the Vietnam series, he first addressed a specific war and by Vietnam II he aimed for specificity in his depiction of weaponry and uniforms, to anchor the paintings in their historical moment. Of this painting’s clumsy, awkward-looking figures, Golub said that he wanted them to be “gross, vulgar, clumsy as war”. This clumsiness was achieved, and a suggestion of a “constructed” self was enhanced, by using a large number of photographic sources and combining them to form aggregate figures, so that they are almost collaged, implying that the human subject is itself an aggregate of sources, most from mass media.

There is tension in Vietnam II, between humanism and anti-humanism, the scenario portrayed being in tension with the manner of its depiction, particularly the figures and eyes. The figures’ comic book eyes evoke almost Sadean materialism, the work suggesting an ultimate impersonality and savage determinism at the core of the human. This was the last painting in which a victim’s eyes would look out at the viewer. Following this, he cast aside liberal pathos, for what could be seen as a deterministic nihilism, despite the ostensible element of protest.

Vietnam II is the largest of Golub’s paintings – 10 x 40 feet (294 x 115 cm). Like his other large paintings, it is unframed and hung at floor level, an act of aggression aimed at the viewer. He may also have been influenced by the size and landscape format of the cinema screen, as well as using such scale as a way of distancing his depiction of the war from that on the small, square television screen. With its dour palette of the quasi-khaki of raw canvas, its dried-blood reds, blacks, and browns, there is a refusal of the haptic qualities of brighter colors and their powers of stimulation, a reaction against the bright palettes of both Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism and the blandishments of advertising, a deliberate making-ugly. These are the colors of the squalid, ugly, smelly mess of violent death, and also suggest an inner “lifelessness” and lack of affect.

Leon Golub, Gigantomachy I, 1965, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

The specificity of the uniform and gun that Golub aimed for in the Vietnam paintings makes the painting no less essentializing than the Gigantomachy paintings: this historical accuracy in weapon and uniform depiction is lost on most viewers of the paintings. Even on close examination, Golub’s rendering of these items makes them seem generic. In both series, he is allegorizing senseless brutality and the two sets of figures in Vietnam II are no less “essential” or “eternal” than those in the earlier Gigantomachy paintings. Vietnam II does not refer to any particular incident in the Vietnam war; the incident, like the figures in it, is an aggregate. However much a painter may want to communicate with his contemporaries, historical specificity in a painting is a temporal illusion, and any depiction of brutality can be read as a synecdoche of the whole bloody nightmare of history.

From the mid-1950s, Golub had been scraping his canvases, going right down to the nap in places, and from the time of Vietnam II utilizing a meat cleaver for this. This abrasion of the surface can give the paintings an ancient, ruinous look, which again universalizes the acts of barbarity he depicts. Golub may also be violently attacking the hateful scenes he represents and trying to “attack” such scenes via a kind of sympathetic magic, as well as experiencing vicarious acting out of violence.

Perhaps there is even a deeper, unconscious identification with his oppressing, destructive protagonists. The primitive artist, according to ethnologists, sought power by creating images of power and exercised power over the creatures depicted. Leon Golub’s relationship with the soldiers, mercenaries, and interrogators in his paintings is psychologically complex and troubling, and something of these aspects of the Palaeolithic artist’s atavistic relationship with depicted figures described above is present in his portrayals of violent men.

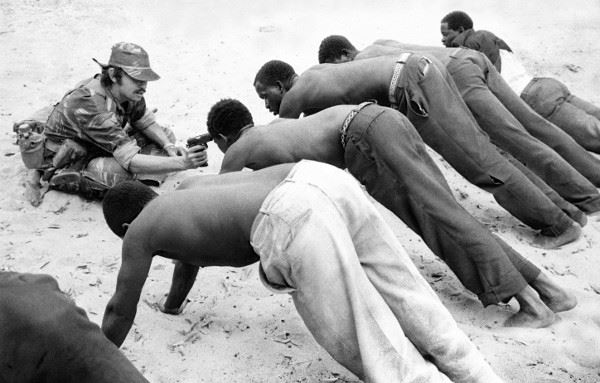

J. Ross Baughman, Interrogation, Rhodesia, 1977. Associated Press.

Mercenaries V is based on an AP Press photo taken in Rhodesia by J. Ross Baughman. Golub made some significant changes from the original photograph, the most obvious being the addition of color, and the torsos of the men being interrogated whilst on all fours now being clothed, their number reduced to three. This latter seems to have been done purely for the sake of elegance of composition and balance.

The original photograph, with the man’s head touching the top of the frame is, by conventional standards, “badly” composed. The figures are evenly spaced, the limbs, including those of the interrogator, are contrapuntally arranged; legs, torsos, and the figure of the interrogator divide the painting into three equal parts, and all of the figures look much clumsier than in the photograph. Whilst in the photograph the ground is clearly sand, Golub’s ground gives the impression that the interrogation is taking place indoors, though we cannot see where the floor meets the wall, giving the impression that the action is taking place in a blueish void. Golub has, then, heavily aestheticized the original source photograph.

Leon Golub, Mercenaries V, 1984, Saatchi Gallery, London, UK.

The paint for the black men’s faces has been much more evenly applied and has not been attacked with solvents and cleaver in Golub’s customary way, unlike the white man, whose face looks diseased, the external acting as a metonym for the diseased and corroded interior. Golub has vicariously committed an act of violence on this patchworked, scarecrow-like character. Another obvious difference is that the interrogator in the photograph wears military fatigues, whilst in the painting, he is in civilian clothes. The uniform is an inhibitor of identification for the viewer, and this is why Golub has eschewed it.

Significantly, the interrogator in the photo does not look obviously Anglo-Saxon, unlike Golub’s protagonist. The interrogator points his gun at a head and his outspread left hand at the scene as a whole, as if it is some kind of grotesque tableaux vivant laid on for the viewer’s delectation, which of course, it is. The mercenary’s eyes look directly into the viewer’s, and he smirks at us in rueful triumph. Few painters have their protagonists look directly at the viewer like this, in a way that reels the viewer into the situation viewed.

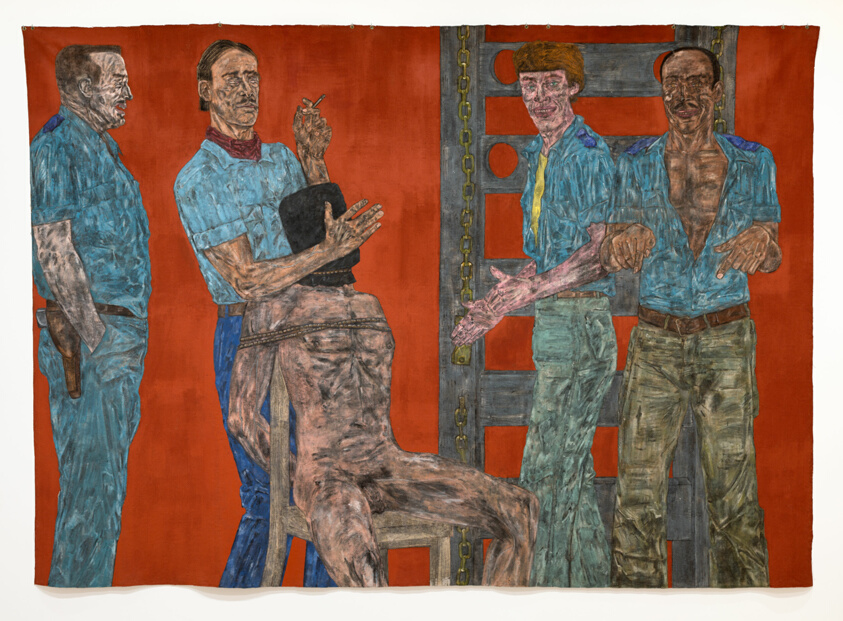

Leon Golub, Interrogation II, 1981, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

In Interrogation II, we again see an elegant patterning of verticals and diagonals, which works somewhat against Golub’s intention to make-ugly. Also, there are similar hand gestures that point, in an artificial way, and which are meant solely for whoever is looking at the painting, and that would not form part of the interrogation.

Here, the third figure on the right, like the figure on his right, is also smiling. He points at the genitals of the man being interrogated, whilst the man beside him smilingly points with both hands at his own genitals. This may be a jeering indication that something gruesome is about to happen to the genitals of their prisoner, but it also sardonically points to the source of male aggression. There is almost no recession to Interrogation II and we feel that the characters are almost in our space, whilst the furnace-red ground gives a hellish feel of the scene taking place in a no-space, and therefore in a no-time, or all-time.

The smiles of three of these figures are directed at the viewer; this disquiets, as when one smiles at someone, one expects the smile returned, and a further level of complicity and identification is created. The victim is hooded. In none of the Mercenary, White Squad and Interrogation paintings, do we see the victim’s face. This lack of a face confirms the distance not only between the oppressor and oppressed but also between the viewer and the oppressed. There is a refusal of any feeling of any identification being fostered, and therefore of pathos, rendering concrete the utter loss of selfhood of the victim, and we experience the act of objectifying him. This, and the torturers being given a face, and their eyes meeting ours, is a brutal emotional and moral realism, which brings us closer to the perpetrators than to the victims.

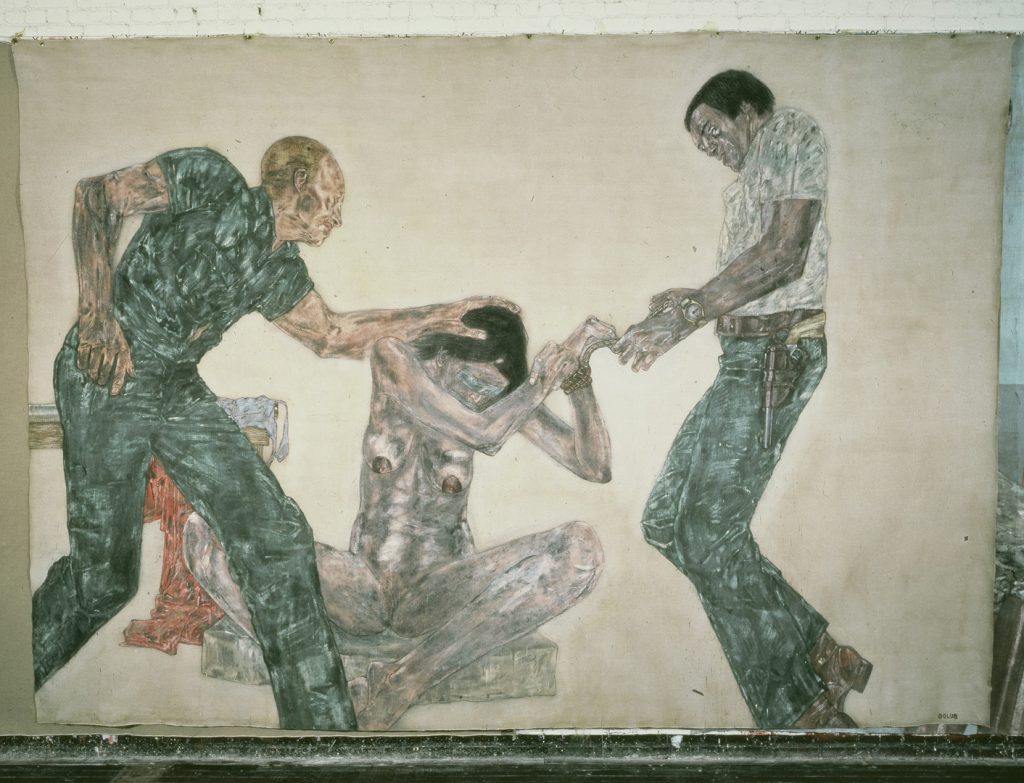

Leon Golub, Interrogation III, 1981, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

In Interrogation III, similarly, the female victim, whose naked body is the cynosure of the canvas, has had her eyes and mouth taped over and her nipples and genitalia eerily seem to stare out at us, forming a primitive schematic face, as we search for a face on her body in order to resist complicity in objectifying her.

Making violence a subject of art necessarily aestheticizes it, even when attempting to capture its squalid quiddity to render it abhorrent. Few painters have dealt with politically produced disquisitions on political violence and brutality as Leo Golub did. E. M. Cioran wrote that only a monster can see things as they really are: Golub exhibited this monstrous strength. His attitude towards male brutality is certainly ambivalent.

His art gives voice to suffering, but, bravely, he also gives one to cruelty. He once commented that his oppressors are just portrayed as “guys on the job, maybe even taking pride in a job well done”. There is no doubt that Golub reviled American neo-colonial violence in South-East Asia, and the covert political violence in South Africa and Central America’s “dirty wars” he portrayed in his works after Vietnam II. His choice of the subject matter suggests condemnatory protest, but at the same time, obsession.

Author’s bio

Chris Milton is a freelance journalist and art historian based in the north of England. He can be reached for commissions via email – [email protected].