William H. Johnson in 10 Artworks—From Post-Impressionism to Folk Art

William H. Johnson’s paintings show a breadth of styles ranging from realism to Post-Impressionism, and later a folk art aesthetic that would...

Theodore Carter 12 February 2026

For many of us, the word “pirate” evokes images of an era full of gallant white-sailed ships, skull and crossbones flags, red bandanas, gold jewelry, and colorful sashes. This romantic, storybook pirate harkens back to the Golden Age of Piracy, roughly 1650–1730, and was defined visually by American illustrator Howard Pyle and his successors in the early 20th century.

Howard Pyle, Captain Keitt, 1911, from Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates, 1921, Wikipedia Commons (public domain).

Roughly 150 years after the Golden Age of Piracy, the Golden Age of Illustration began. Advances in technology had made color printing cheaper and easier, and televisions had not yet entered American homes. Howard Pyle, often called the Father of American Illustration, ushered in this Golden Age through his own work and through his Brandywine School—a name given to artists influenced by Pyle’s work and teachings in Pennsylvania’s Brandywine Valley.

Pyle’s exemplary skill as a painter, his meticulous research, and the influence of his teaching reverberate through narrative art today. More specifically, storybook pirates, as defined by Pyle, were repeatedly depicted by the Brandywine artists.

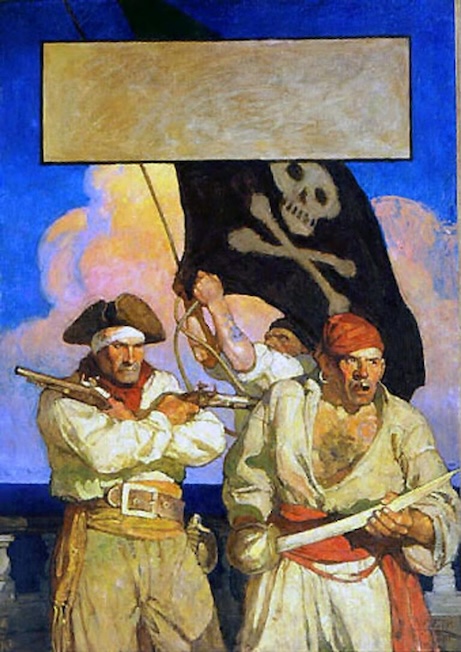

Howard Pyle, Who Shall Be Captain, 1908, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE, USA. Museum’s website.

Along with his dedication to historical accuracy, Pyle was also a storyteller. Understanding how to capture an audience, he created pirates who were an amalgamation of actual pirates and sailors attire, mixed with his own colorful additives.

“Since visual imagery documenting the appearance of early pirates was scant at best, Howard Pyle examined antique prints and manuscripts while perusing his personal archive of historical costume records to create convincingly seductive portrayals of pirates that were drawn largely from his imagination,” writes Stephanie Plunkett, chief curator at the Norman Rockwell Museum. “So lifelike were Pyle’s illustrations that viewers suspended disbelief and accepted with enthusiasm the authenticity and theatricality of his vision.” Plunkett specifically notes the red scarves, stormy backgrounds, and animated expressions in Pyle’s pirate paintings.

Howard Pyle, Marooned, 1909, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE, USA. Artchive.

In reality, there’s little reason to think pirates dressed much differently from everyday sailors. F. T. Merrill was the first illustrator of Robert Louis Stevenson’s classic pirate story, Treasure Island, in 1884. While those illustrations are full of adventure, it was Pyle who first painted pirates the way we imagine them today in an 1887 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. For years afterward, Pyle continued both writing about and painting pirates. Ten years after his death, his writing, paintings, and drawings were collected into Howard Pyle’s Book of Pirates.

N. C. Wyeth, Cover illustration for Treasure Island, 1911, private collection. Brandywine Museum of Art.

When Howard Pyle started his school of illustration in 1894, N. C. Wyeth enrolled and became an eager protegé. Within months of beginning his tutelage, Wyeth landed a Saturday Evening Post cover at the age of 21.

N. C. Wyeth, Illustration for Treasure Island, 1911, Brandywine Museum of Art, Chadds Ford, PA, USA. Museum’s website.

In 1911, when Scribner’s sought an illustrator for a rerelease of Treasure Island, they chose Pyle’s young, exemplary student. Wyeth’s Treasure Island paintings retained much of the iconography invented by his mentor. Wyeth also went on to illustrate several Captain Blood pirate-themed books by Italian-American author Rafael Sabatini.

Frank Schoonover, Pirates Coming Through Charleston, 1922, private collection. Antiques and the Arts Weekly.

Frank Schoonover studied with Howard Pyle at Drexel University, where he sat in class with artists Violet Oakley, Thornton Oakley, Maxfield Parrish, and Jessie Wilcox Smith. When Pyle left to form his own school in Chadd’s Ford, Pennsylvania, Schoonover followed. Over his 60-year career, Schoonover illustrated more than 200 books, including a 1921 edition of Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and Blackbeard Buccaneer.

Frank Schoonover, Cover of Blackbeard, Buccaneer, 1922. Wikipedia Commons (public domain).

A brilliant, highly varnished cadmium red, known as “Schoonover red,” became a signature element in many of his works and is unmistakable in his pirate paintings. To fully experience the realism he sought to illustrate, Schoonover traveled extensively. At home, he worked in a Wilmington, Delaware studio just a stone’s throw from Pyle.

Dean Cornwell, Captain Blood, illustration for American Magazine, 1930, private collection. Invaluable.

Though not a direct student of Pyle, Dean Cornwell became an artistic descendant of the Father of American Illustration through his teacher, Harvey Dunn. Cornwell, a prolific commercial illustrator, signed a lucrative $100,000 contract with Cosmopolitan magazine in 1926, equivalent to about $1.8 million today. Cornwell illustrated stories by Somerset Maugham and Ernest Hemingway while working for Cosmopolitan.

Dean Cornwell, Captain Blood Inspecting the Treasure Chest Jewels, illustration for Cosmopolitan, 1930. Illustration History.

A year later, Cornwell sought more lasting recognition for his art. He switched to muralism and was commissioned to paint a large-scale work for the Los Angeles Public Library. He would return to illustration from time to time because he could command top dollar. In 1931 he illustrated Captain Blood Returns, a book perhaps lacking the literary clout of Hemingway but containing as much swashbuckling as can fit in any one book.

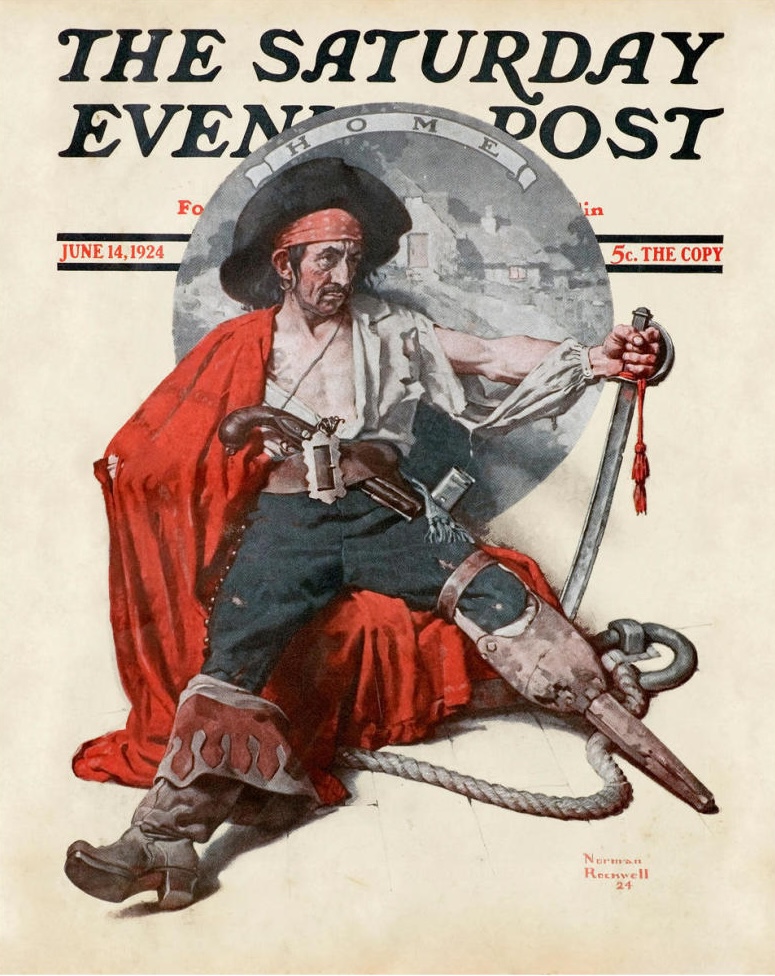

Norman Rockwell, Thoughts of Home, 1924, Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA, USA. Museum’s website.

Best known for nearly 40 years of Saturday Evening Post covers, Norman Rockwell, perhaps more than any other artist, helped define the American Dream. Though not a formal member of Pyle’s Brandywine School, he was heavily influenced by it, as is evidenced by his meticulous research and exacting detail.

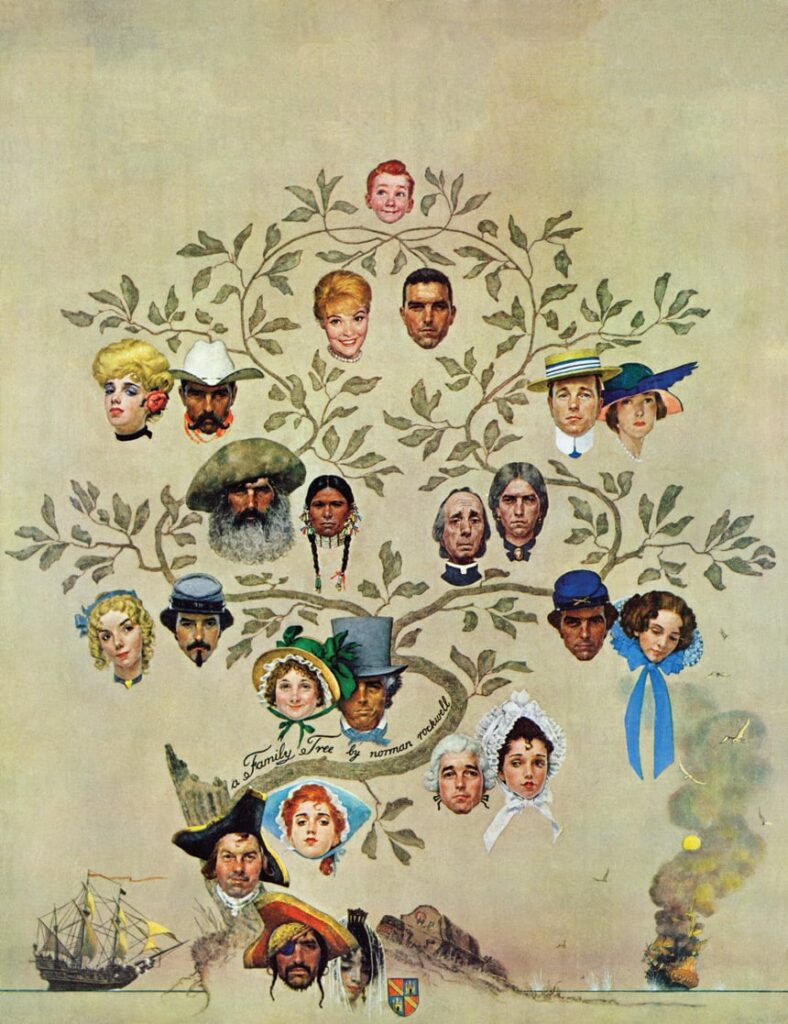

Norman Rockwell, Family Tree, 1959, Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA, USA. The Saturday Evening Post.

A reproduction of Pyle’s Captain Keitt hung in Rockwell’s studio, and his own oeuvre includes several pirates. The red cape, bandana, and peg leg pirate on Thoughts of Home from the June 14, 1924, Saturday Evening Post, certainly harken back to Pyle’s Treasure Island paintings. Still, if there was any doubt, Rockwell spells it out in his painting, Family Tree, with a small “H. P.” inscribed in the treasure chest at the base of the tree.

While these artistic descendants of Pyle carried on his vision of pirates, so did Hollywood. The images created during the Golden Age of Illustration defined the way pirates appeared on screen—from early silent films to Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean franchise. What we now picture in our minds as a pirate owes much to Howard Pyle and his Brandywine School.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!