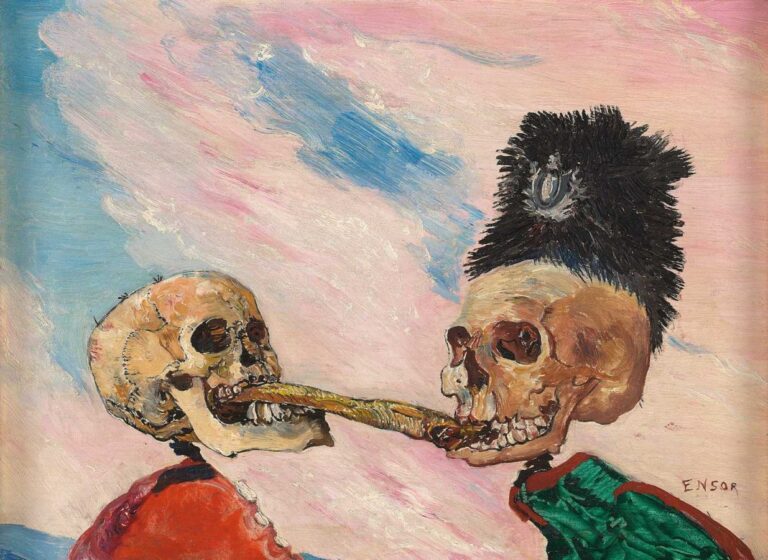

Halloween is coming and in our team we were thinking who should we feature tomorrow on our DailyArt app (available for free on iOS and Android). It’s so easy to go with Füssli and his Shakespeare-like scenes, Goya horrible black paintings or Dali crazy imaginations. But then something reminded me of James Ensor who in his art was obsessed with skulls, circus and masks, all painted in those sweet bright colors which made his creepiness even stronger.

James Sidney Edouard, Baron Ensor was a Belgian painter and printmaker, an important influence on expressionism and surrealism who lived in Ostend for almost his entire life. He was associated with the artistic group Les XX.

From 1877 to 1880, he attended the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, where one of his fellow students was Fernand Khnopff.

During the late 19th century much of his work was rejected as scandalous, particularly his painting Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889 (1888–89).

The Belgium art critic Octave Maus famously summed up the response from contemporaneous art critics to Ensor’s innovative (and often scathingly political) work: “Ensor is the leader of a clan. Ensor is the limelight. Ensor sums up and concentrates certain principles which are considered to be anarchistic. In short, Ensor is a dangerous person who has great changes. . . . He is consequently marked for blows. It is at him that all the harquebuses are aimed. It is on his head that are dumped the most aromatic containers of the so-called serious critics.”

Some of Ensor’s contemporaneous work reveals his precocious response to this criticism. For example, the 1887 etching “Le Pisseur” depicts the artist urinating on a graffited wall declaring (in the voice of an art critic) “Ensor set un fou” or “Ensor is a Madman.”

Many of his paintings feature figures in grotesque masks inspired by the ones sold in his mother’s gift shop for Ostend’s annual Carnival. Subjects such as carnivals, masks, puppetry, skeletons, and fantastic allegories are dominant in Ensor’s mature work. Ensor dressed skeletons up in his studio and arranged them in colorful, enigmatic tableaux on the canvas, and used masks as a theatrical aspect in his still lifes. Attracted by masks’ plastic forms, bright colors, and potential for psychological impact, he created a format in which he could paint with complete freedom.

The four years between 1888 and 1892 mark a turning point in Ensor’s work. Ensor turned to religious themes, often the torments of Christ. Ensor interpreted religious themes as a personal disgust for the inhumanity of the world.In 1888 alone, he produced forty-five etchings as well as his most ambitious painting, the immense Christ’s Entry Into Brussels in 1889. Also known as Entry of Christ into Brussels, it is considered “a forerunner of twentieth-century Expressionism.” Identifiable within the crowd are Belgian politicians, historical figures, and members of Ensor’s family.

Even in the first decade of the 20th century, however, his production of new works was diminishing, and he increasingly concentrated on music—although he had no musical training, he was a gifted improviser on the harmonium and spent much time performing for visitors. He died there after a short illness, on 19 November 1949.

Find out more:

[easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”1910350451″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/61E1DwZGxSL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”127″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”3775724656″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/610B9VtkhRL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”121″] [easyazon_image align=”none” height=”160″ identifier=”3775737227″ locale=”US” src=”https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/51I5HGmR9JL.SL160.jpg” tag=”dailyartdaily-20″ width=”106″]