1. Romantic Landscape by Wassily Kandinsky

Wen-Ling Chung, Art Education and Mediation Fellow

When I first entered the exhibition room, I wasn’t immediately captivated by this painting. Day after day, I found myself becoming drawn into it—it was a walk. A walk alone in the middle of the night. I stepped deep into the snow and looked at my own shadow. Then I shifted my gaze to the right. Through the trees, I saw: three chubby horses carrying three travelers, rushing through the valley.

Everything was in a rush. The thickness of the paint, the speed of the brushstrokes, the unhesitating touch, the three travelers, the three horses. But the earthy, grounded color kept the moment firmly. The red-orange moon hung high in the sky, almost ominously. They didn’t seem to be running away from something; rather, they seemed to be running toward something—where, we don’t know. As with ourselves.

2. Self-Portrait with Skeleton by Lovis Corinth

Karin Althaus, Curator for the 19th and Early 20th Centuries

Memento mori—remember, you too will die one day. This idea has left its mark on art history over many centuries. Lovis Corinth now treats the subject in a “modern” way—humorously on the one hand, but with a clear view of his own mortality.

The skeleton looking cheekily over his shoulder is an artist’s prop standing around in the studio. Corinth describes himself in the signature as 38 years old: he looks older, worn out, and he seems to know it. This is the first painting in a series of self-portraits that he painted on his birthdays from then on. Now and then, death also peeks into the picture. Not a bad way to question yourself at least once a year.

3. Neubau by Käte Hoch

Adrian Djukić, Librarian

The new building in Käte Hoch’s painting appears to be something very alive—hardly a mere construction site, and even less a future “property.” The unfinished building stands isolated, with only partly torn posters bearing witness to the promises of the big city.

It evokes the construction boom of the Weimar Republic, which responded to the housing shortage and was associated with revolutionary ideas involving new materials and designs. Käte Hoch embodies these expectations in several ways. As a representative of the “New Woman” of the Weimar Republic, she was committed to the training of female artists. She was active in left-wing circles in Munich, organizing events and distributing leaflets against the rise of National Socialism. Although the times offered little cause for optimism, her unobtrusive works convey the unfortunately often forgotten idea of searching for better social models for all.

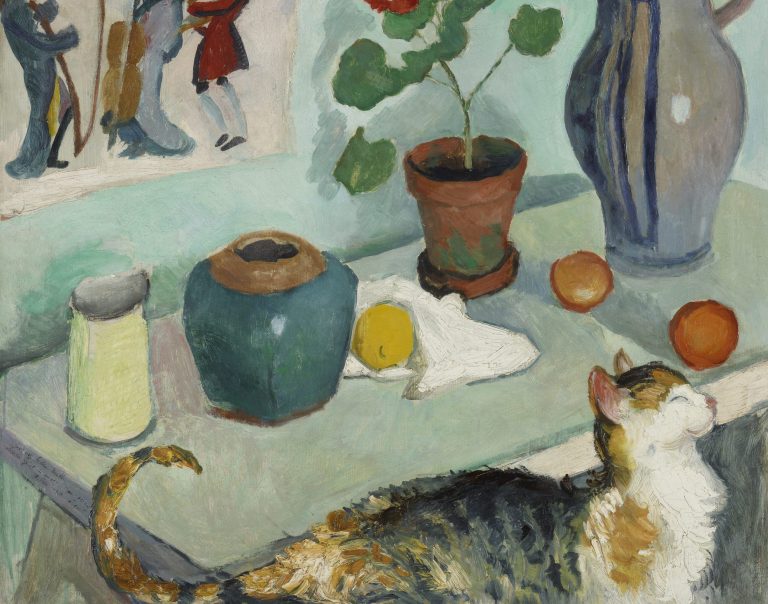

4. The Spirit in the House Stalls: Still Life with Cat by August Macke

Elsa Li, Communications Fellow

Here we have August Macke’s still life, and what I especially like about it is the presence of lively elements such as the cat, the green potted plant, and the poster with the musicians hanging above the table. The artwork also features beautiful, bright pastel colors, which stand in complete contrast to the darker still lifes one is usually familiar with. All in all, to me, it is a very vibrant still life that radiates a positive atmosphere.

5. Tiger by Franz Marc

Thomas Staska, Accounting

I like Franz Marc’s Tiger because it stands out so well against the colorful background in its bright black and yellow outfit. The green, red, and blue in the background really make the tiger look beautiful.

6. Night in St. Prex by Alexej von Jawlensky

Lukas Schramm, Photographer

Night in St. Prex appears like a tranquil, almost dreamlike scene in soft dark tones and small patches of light. The simple forms make the image completely relaxed yet atmospheric. One has the feeling that the place is only briefly illuminated by the moonlight.

7. Self-Portrait by Käte Hoch

Lisa Kern, Art Provenance Research / Collections Archives

Käte Hoch (1873–1933) painted her self-portrait in 1929, and it was probably created in her Munich studio in Schwabing. In it, Hoch presents herself as a self-confident artist with a palette, brush, and easel, while also positioning herself as a political activist. I interpret the balloon cap and the red and purple of her clothing as visual codes for her stance as a women’s rights activist and a socialist, and at the same time as a commitment to the working class.

Käte Hoch studied in Paris and at the Munich Women’s Academy. In the 1920s, she belonged to the circle around the writer Oskar Maria Graf and the Jungmünchner Kulturbund, which campaigned against the rise of National Socialism in Munich. In the spring of 1933, just a few weeks after the Nazis came to power, a gang of SA thugs attacked the artist in her Schwabing apartment and destroyed her works. Hoch died shortly afterward at the age of 60 under circumstances that remain unclear.

The painting is one of my personal favorites in the Lenbachhaus collection. It tells not only the story of the artist’s life, but also of the late Weimar Republic, of courage, conviction, and resistance. After Käte Hoch and her work had long been forgotten, they were rediscovered at the Lenbachhaus a few years ago. Today, we can tell her story in the museum and remember this important artist.