Masterpiece Story: The Setting of the Sun by François Boucher

With sweet putti, handsome gods, beautiful nymphs, vibrant colors, and elaborate compositions, The Setting of the Sun is a testimony to François...

James W Singer 8 February 2026

17 July 2025 min Read

The world has recently bid farewell to Arnaldo Pomodoro, the Italian sculptor whose name became synonymous with monumental bronze spheres—enigmatic objects that blend perfection with rupture, order with chaos. Born in 1926 in Morciano di Romagna, Pomodoro spent his life crafting works that seem suspended between ancient relics and futuristic artifacts. His death marks the end of an extraordinary artistic journey, yet his works continue to challenge, provoke, and mesmerize.

Arnaldo Pomodoro, Sphere Within a Sphere, 1986, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. Archivio Scultura.

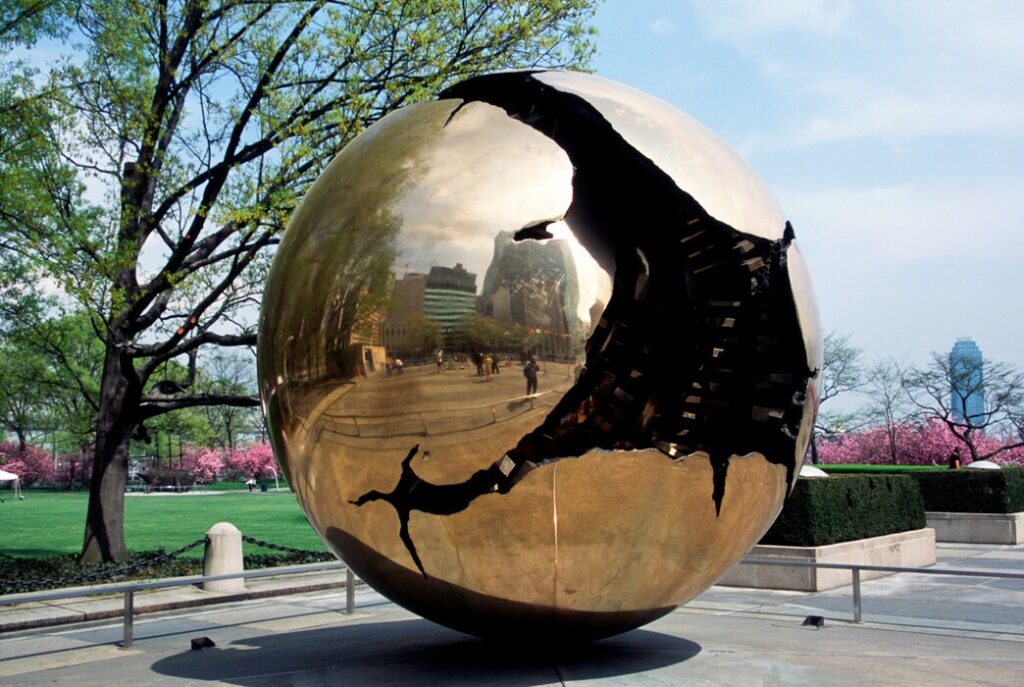

Pomodoro’s artistic language is instantly recognizable: polished, geometric perfection fractured by intricate, labyrinthine interiors. His iconic Sfera con Sfera (Sphere Within Sphere) series adorns plazas and museums worldwide—from the Vatican Museums in Rome to Trinity College in Dublin and the UN Headquarters in New York. But his work extends far beyond spheres: towering obelisks, columns, and totems, all bearing the same duality of exterior perfection split open to reveal chaotic, almost mechanical innards.

Nestled within the Museo del Novecento in Milan is one of Pomodoro’s most intriguing pieces: Sphere No. 5. At first glance, it’s a perfect sphere—gleaming, symmetrical, commanding. Like a sacred celestial body, it captures light and space around it, a timeless shape that feels both eternal and alien.

Arnaldo Pomodoro, Sphere No. 5, 1965, Museo Novecento, Milan, Italy. Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro.

But then, your eyes are drawn to the ruptures—rough, spiky, yet unsettling. The shell of the sphere is torn open in places, revealing an impossible inner landscape. It’s like being exposed to the circuitry of an artifact left behind by an ancient alien civilization. The polished bronze fractures open like tectonic plates, revealing a dense network of geometric structures, grids, beams, and cavities.

Is it broken? Or was it always meant to be this way?

There’s something profoundly hypnotic about the contrast. The smooth, flawless exterior evokes strength, completion, indestructibility—the very idea of perfection. And yet, these gaping wounds break that illusion. They are not random cracks; they are architectural voids, meticulously carved and impossibly complex.

Arnaldo Pomodoro, Sphere Within Sphere, 1996, United Nations Art Collection, New York City, NY, USA. UN.

[The sculpture] reflects and accommodates the environment with its own complex mix of imagery that can be seen as both humanistic and technology-oriented: a smooth exterior womb erupted by complex interior forms. Timely in its introduction, the sculpture is intended as a metaphor for the coming of a new millennium, a promise for the rebirth of a less troubled and destructive world.

Standing before Pomodoro’s Spheres, one cannot help but feel the pull of the unknown. The openings seem less like damage and more like portals—inviting, even demanding, that we look inside. What lies within could be anything: the mechanical guts of a universe-spanning machine, a labyrinth of infinite reflections, or a visual metaphor for the hidden workings of reality itself. It feels less like an object and more like an interdimensional device—something far beyond human understanding, quietly vibrating in the corner of our existence.

And perhaps, that’s the point. Pomodoro’s Sphere isn’t just a sculpture—it’s a psychological landscape. It’s a mirror of our own minds. From the outside, we construct identities—polished, intact, consistent. But beneath that surface lies a fragmented, chaotic architecture of thoughts, memories, contradictions, and unresolved questions.

Arnaldo Pomodoro, Sphere Within Sphere, 1990, Vatican Museums, Vatican City. Museum’s website.

In this way, Pomodoro’s sculptures become a physical manifestation of our inner worlds. Are we truly whole? Or are we, like the spheres, collections of fragments held together by the illusion of coherence? Are we one? None? Or a hundred thousand selves, shifting and overlapping like the facets within these impossible objects?

This is what drives me to create the spheres: to break these perfect and magical forms in order to discover (to search for, to find) their inner fermentations—mysterious, living, monstrous, and pure. In doing so, I create, through the polished smoothness, a contrast, a dissonant tension, a sense of completeness made of incompleteness. In the same act, I free myself from an absolute form. I destroy it. Yet, at the same time, I multiply it.

“Arnaldo Pomodoro Sphere Within a Sphere for the U.N. Headquarters,” Il Cigno Galileo Galilei, Roma 1997, pp. 14–15. Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro.

There’s a reason why Pomodoro’s Spheres resonate so deeply decades after their creation. They are timeless precisely because they sit at the edge of meaning—neither fully decipherable nor entirely opaque. They do not offer answers; they offer entry points. A chance to contemplate the tension between surface and depth, between the desire for perfection and the inevitability of fracture.

Ultimately, standing before these alien giants feels like standing before a portal—not just to other worlds, but to the multiverse within ourselves.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!