Masterpiece Story: Opéra Garnier

When we talk about the beautiful sights of Paris, many first think of the obvious ones—the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre Museum, and the Notre-Dame...

Nikolina Konjevod 26 September 2025

4 August 2025 min Read

American cities are renowned for their many architectural landmarks, featuring ornate domes, columns, and sculpted façades. Less widely recognized, however, is the role played by Italian and Sicilian immigrants in shaping these structures. Beginning in the late 19th century and continuing into the early 20th century, artisans from Italy, particularly from Sicily, arrived in growing numbers with centuries of expertise in masonry, sculpture, and stone carving. Their legacy remains embedded in the buildings they helped create.

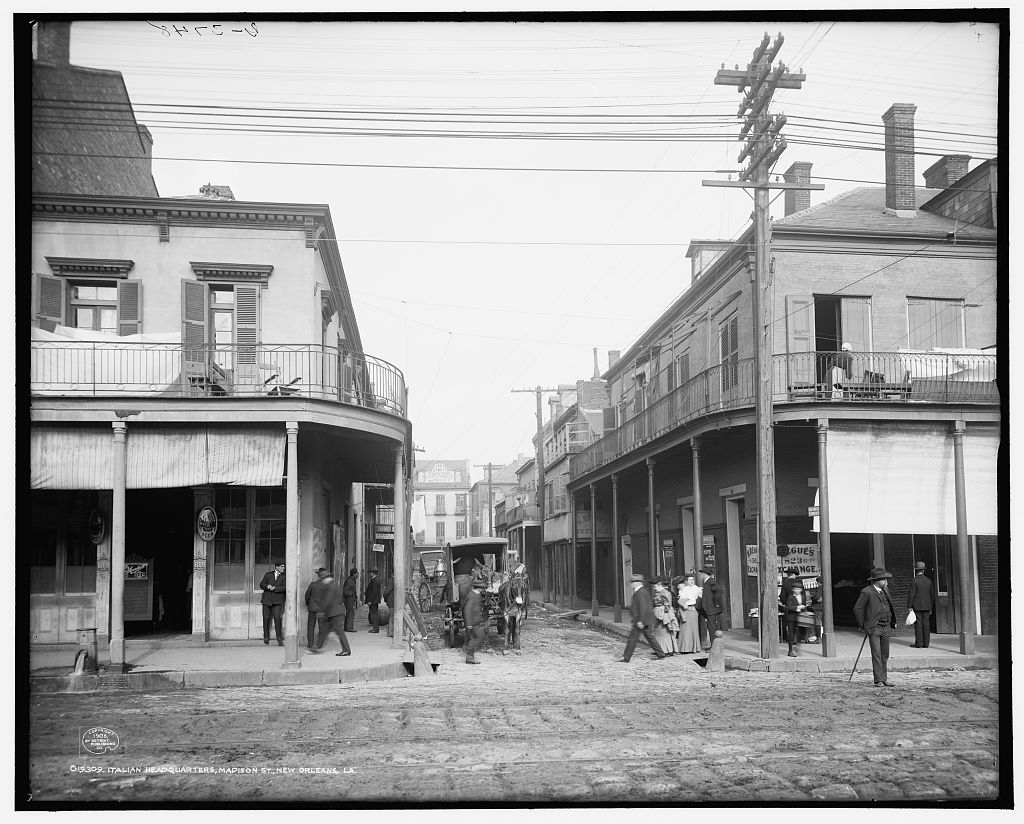

Driven by poverty and limited opportunities at home, many Italians and Sicilians sought a better life in the United States. They settled in cities such as New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, and New Orleans, often forming close-knit neighborhoods that provided cultural support and economic stability during the process of adaptation and integration. Many found employment in construction and stonework. Their traditional skills made them valuable workers during America’s rapid urban expansion.

In addition to working as stone masons and tile setters, they also found employment as carpenters, bakers, plumbers, and other skilled tradespeople. Some also migrated to rural areas for agricultural and manual labor. Over time, many of these immigrants remained, raising families and contributing to the development of their new communities.

Christopher Grant LaFarge, George Lewis Heins, Ralph Adams Cram, Cathedral of St. John the Divine, 1892–1941, New York City, NY, USA. Photograph by Kripaks via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-3.0).

Italian and Sicilian stoneworkers often came from regions with long traditions of marble and limestone carving. Towns such as Carrara, Custonaci, Trapani, Palermo, and Catania trained generations of artisans in techniques rooted in Roman, Byzantine, and Baroque design. These skills were well-suited to the monumental civic architecture taking shape in the United States.

Their arrival coincided with the rise of the City Beautiful movement, which emphasized classical grandeur in urban planning. Architects and planners relied on trained craftsmen to bring their blueprints to life, and these skilled artisans met this demand.

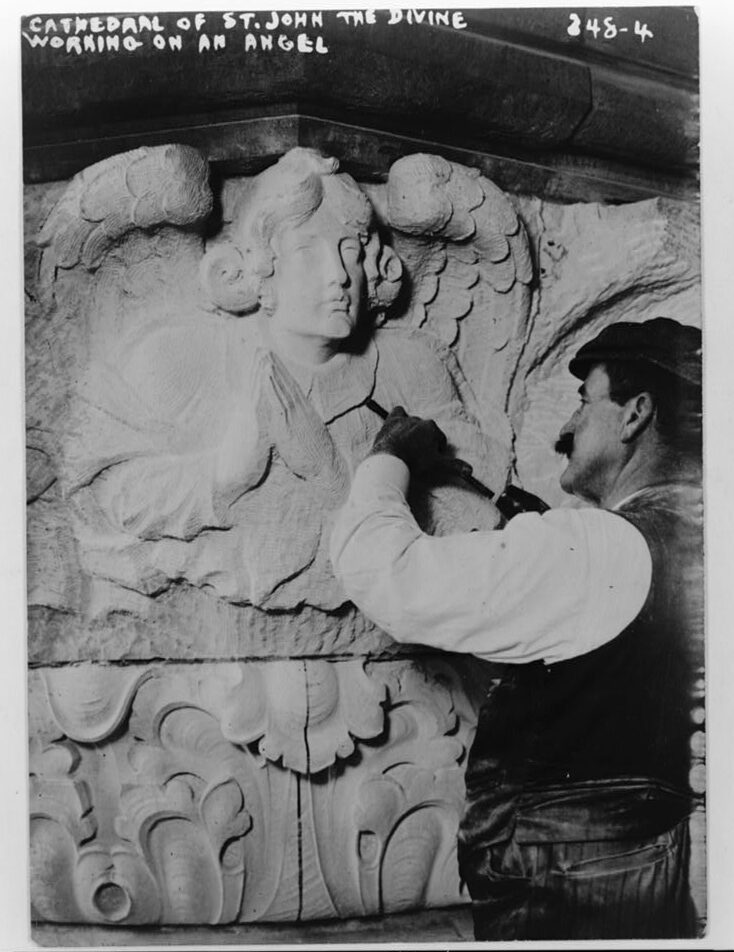

Man working on Cathedral of St. John the Divine, 1909, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

By the early 1900s, Chicago had become a hub for stone carving and masonry. Many Sicilian immigrants found work in the wake of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The exposition’s Beaux-Arts buildings, though temporary, created a lasting appetite for classical architecture in the city. The event sparked a demand for permanent, classical stone architecture across the city, which is apparent in the churches, public buildings, and ornate façades that define downtown Chicago.

Piccirilli brothers, Bronx, New York. Photograph by John Freeman Gill. New York Times.

Among the most accomplished Italian artisans in the United States were the Piccirilli brothers, six sculptors from Carrara who established a studio in the Bronx in the 1890s. Although they often worked from the designs of prominent sculptors, they carved some of America’s most iconic monuments. Their work includes the lions outside the New York Public Library, the pediment of the New York Stock Exchange, and the statue of Abraham Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial. Despite their central role in shaping public art, they often went uncredited.

Chicago Cultural Center, 1897, Chicago, IL, USA. Photograph by David K. Staub via Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.5).

Italian artisans left a lasting mark far beyond New York and Chicago. In Washington, DC, they helped construct the Library of Congress and Union Station, both of which are admired for their detailed stonework. After the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco’s reconstruction drew many Italian and Sicilian stoneworkers to projects like Grace Cathedral. In St. Louis, the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis showcases a blend of European architectural styles shaped in part by Italian craftsmanship.

Italian headquarters at Madison St., New Orleans, c. 1906, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, USA.

Despite their skill and contribution, Sicilian immigrants were often targets of suspicion and prejudice. In the racial hierarchies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Southern Italians were frequently viewed as outsiders due to their language, customs, and appearance.

Stereotypes painted Sicilian immigrants as uneducated laborers or criminals. These biases worsened with the rise of organized crime. In many cases, mutual aid societies created to protect immigrants were conflated with criminal networks, and as the Mafia gained notoriety, it cast a dark shadow over the wider Sicilian-American community.

The most tragic consequence of this climate came in 1891, when 11 Sicilian men were lynched in New Orleans. Following the acquittal and mistrial of several Italian defendants accused of murdering Police Chief David Hennessy, a mob broke into the Parish Prison and executed the men by force. It remains one of the largest mass lynchings in American history.

Lewis P. Hobart, Grace Cathedral, 1927–1964, San Francisco, CA, USA. Photograph by Daderot via Wikimedia Commons.

In the face of hardship and hostility, Italian and Sicilian immigrants built lasting legacies. They trained apprentices, founded churches, and preserved artistic traditions that continue to shape American architecture. Today, their contributions are often unsigned but remain unmistakable in the curve of a Corinthian capital, the face of a saint hidden in a pediment, or the flourishes carved into a courthouse cornice. These quiet embellishments are reminders of hands that came from Italian and Sicilian quarries to help shape a new nation in stone.

DailyArt Magazine needs your support. Every contribution, however big or small, is very valuable for our future. Thanks to it, we will be able to sustain and grow the Magazine. Thank you for your help!