“Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,” Robert Frost begins. His poem Mending Walls is emblazoned next to the entrance, setting the tone for the Annenberg Space for Photography’s latest exhibition. Even before stepping inside, we are primed to explore walls’ ambiguity and ubiquity in human lives.

The first work to greet visitors inside the walls is Thomas Van Houtryve’s video Divided (2018), featuring birds-eye footage of ocean waves split by a human-made wall at the US/Mexico border. Seeing this arbitrary line in the water, the surf forced to curve around it, prompts the viewer to ask about the ways we divide the world. Nature may abhor a wall, but humans seem to keep building them.

The main question, of course, is why? The wall text lays out David Frye’s argument that civilization has always been bounded by, and flourished within, walls. Living within agreed-upon rules and boundaries enabled loosely organized groups to become societies, from the earliest walled cities to our current national borders. Civilizations require structure. And while it can be frustrating to live within conformity, there are downsides to living beyond the pale as well. Walls protect as well as divide.

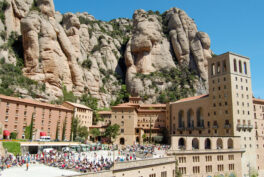

The show is built thematically around six functions of walls: Delineation, Defense, Deterrent, Decoration, The Divine, and The Invisible. Of these, the weakest is The Divine, which offers a few photographs of religiously significant walls but fails to convince that this aspect carries the same import as the others. (The alliteration could perhaps have been sacrificed for the more robust category of Memorial.) However, the overall structure works well, juxtaposing examples of ancient and contemporary walls with abstract conceptions to create a holistic picture of what walls can do.

“Before I built a wall I’d ask to know / What I was walling in or walling out,” Frost wrote. The exhibit explores this question as well – first with the people who are caged within ghettos, prisons, refugee and internment camps. The poignant images of this section include Carol Guzy’s Albanian Refugee Camp (1999), which shows a toddler being passed between barbed wires to visit with relatives. The contrast of sharp and soft sides of humanity has rarely been so well encapsulated in a single image. The exploration of deterrent walls is just as topical, including tension-filled photographs of the US/Mexico border and other current sites of contention.

Defense explores ancient fortified cities, today sapped of their power as terrifying fortresses by the banality of tourism. The Berlin Wall, however, retains its power as one of the more famous defensive walls in living memory. The photographs show the oddities and latent dangers of life in a divided city, as well as the near-universal joy when the wall was destroyed. The exhibit uses this particular wall to point out that, despite its proven inefficacy, walls have only proliferated since. When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, there were 15 border walls around the world; in 2018, there were 77.

Invisible walls are perhaps the most important to explore and the hardest to photograph. The concepts of redlining and other insidious forms of segregation are captured in this section of the exhibit, as well as Marina Abramović’s melding of physical and psychological walls in her Great Wall Walk (1988/2008). Though powerful, the images skim the surface of a topic that could easily form an exhibit of its own.

Ultimately, what emerges from this exhibit is the essential futility of walls. Walls can and will be breached; the sense of protection they provide stems more from their intellectual and emotional construction rather than their physical existence. We may feel safer behind walls, because living without them requires a great deal of trust. But in the face of those 77 walls (and counting), it seems important to spell this out: walls are a temporary barrier, not a permanent solution.

An installation towards the end of the exhibit offers visitors the opportunity to answer the question, “What’s blocking your path?” The scrolling projections of responses is quite moving, the candid confessions of worries driving home how similar we are behind our walls. All walls, in the end, are about fear; knocking them down is about shared humanity and vulnerability. Another line comes back to me from Frost’s poem: “we keep the wall between us as we go.” What would happen if we didn’t?

W|ALLS: Defend, Divide, and the Divine

Curated by Dr. Jen Sudul Edwards, Chief Curator and Curator of Contemporary Art at the Mint Museum, Charlotte, NC

Annenberg Space for Photography

2000 Avenue of the Stars

Los Angeles, CA 90067

Oct 5-Dec 29, 2019

Free Admission

Wed-Sun, 11-6

Anne Wallentine

Anne Wallentine is a freelance writer with an MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art. Her art history background also informs her role as a creative director for PR and design projects. She is particularly interested in feminist and queer history, Japonisme in American woodblock prints, the politics of Northern Renaissance portraiture, and tracking down the next best coffee or gin.